When we tried to pay for parking at the gate, the machine wouldn’t let us go. It refused to read mom’s credit card, so we had to try Hamza’s, who was behind the wheel. That seemed to do the trick, but then the gate wouldn’t lift.

“Does it take coins?” Mom asked, her change purse at the ready.

“Um, not sure—is it a wishing well?” said Hamza.

Dead silence. Mom quietly polished her card’s magnetic strip. My lap full of new library books, I looked out the window at an imaginary mugging taking place.

We tried the whole routine over from the beginning: ticket, card, gate. This time, the machine’s screen said we owed $12.00 instead of the initial $8.00 it said we had to pay.

When we tried to fork over that sum, the machine forgot how to read cards again—now Hamza’s matte black Visa. Little sarcasm this second time. It was increasingly certain we would have to spend the best years of our lives in the gloom of the Seattle Public Library’s parking garage.

Finally Hamza pressed the help button. We all waited.

It seemed that was my cue to puncture the suspicion we were dumb with my famous irony, by embracing that potentiality, lampooning the bad hand dealt us, but I was newly unaccustomed to juggling such a sprawling cast. I’d botched the rhythm of my delivery, forgotten my lines.

Help was a female librarian in a skull print balaclava standing straight as the yellow line of paint between the machine and the driver’s side door. Over us all rushed a fresh, cold dread.

Hamza could no longer find the ticket upon which, it seemed, all goodwill and trust seemed balanced.

As he searched around and under and in the front seat creases, Hamza circled back to the claim that Mom must’ve put it somewhere, though we all agreed it had to be on his person—he’d had it just a moment ago.

Outside the van, the masked woman waited. Thumbs slung from her belt loops.

There was desperation in their search now, as if an hourglass were emptying above us, filling the car with sand. Every second ticking by deepened the red in my faces. Frankly, I had to withstand an urge to smash my window and run.

When at long last the ticket was found (in Hamza’s wallet), we repeated the steps of the process once more, this time monitored by the librarian mercenary, and it said we owed $12.00 again. The masked woman, whom I could not hear very well at all, said the ticket must still be paid.

The smartest of us, Hamza, my brother, ran a university biology lab. Did important, life-saving work. He was a good guy.

Hamza inserted his card once more, and once more, we all waited for the machine’s lone arm to lift and allow us passage. Prayed for the machine to remember. It had been years since any of us had uttered any kind of real prayer at all.

My eight-year-old niece, Jin (Jinani, shh), handed me the pop-up book she checked out because she had developed robust I’m-falling-asleep protocols by that point, and was already nodding off despite the rare sunshine gushing through the windows. I slipped it under the pile of other books and continued reading mine as Hamza drove.

My twelve-year-old nephew, Tad (Tadeen, shh), asked if I wanted to see a meme on his phone.

“Nope,” I said.

I was reading.

Also, I didn’t like my nephew. Bad blood between us of late.

Getting to be that age, is what I kept thinking to myself.

“C’mon,” he said, “It applies to you,” (red flag).

“No, thank you,” I replied in a tone meaning no fucking way.

He fell into a sulk and continued vibing to Eminem in the far back.

That didn’t make me the bad guy though, as I tried finding my place on the page and we crossed the high bridge toward their house.

◆

It was Tad, Hamza, Jin and I on the soccer field. I could see downtown shimmer in the late July heat, a color-bled Emerald City way beyond a wild and thorny blackberry thicket subsuming the far chain link fence.

Two years since I’d last seen any of them and Tad was six inches taller and now fully rabid for soccer. UEFA, FIFA, CONCACAF Champions League—it made no difference. Aside from the supremacy of Marshall Mathers, it was all he could talk about. Hamza was to be next year’s coach, and both said they looked forward to the new dimension in their relationship. Tad had the ball, dribbled past me, took a shot on goal that arced far above the crossbar and into the bramble.

“Jin, go get it!” he yelled.

Hamza knelt before her. “Jin, you’re small,” he said. “Would you mind going around and getting the ball?”

Jin wanted nothing more—she sped around the edge of the fence and plunged in while the rest of us froze in a collective wince. But save a burr clinging to her ash-blond mop of hair, Jin emerged unscathed.

Morale was strong.

“I would’ve made that shot if these stupid goals were regulation,” said Tad, which made me make a dumb face at Hamza, who couldn’t help chuckling.

“Seriously, dad?” said Tad. “You’re not supposed to laugh at me. Don’t make me tell your wife…”

Meaning Gina, with the gold-spun hair her kids inherited.

Hamza closed his eyes, summoning a greater patience, or maybe just counting backwards from ten in his mind.

There were rules, apparently.

I took the ball just shy of midfield.

Hamza in goal, Tad on defense.

The kid made a run toward me. I feigned right but cut left hard, nearly perpendicular to him, which wasn’t ideal, but I was faster than Tad, and possessed a good left foot. So I sprinted with the ball to the sideline, started cutting in, rounding the corner by the penalty box, and let it fly, but I missed, my angle far too wide.

“Ooh, nice one!” Tad yelled. “Shouldn’t’ve used your toe,” he added, being a super expert soccer warlock.

“Hey…” said Hamza, “Take it easy, we’re just messing around…”

Because I don’t have that good left foot anymore. I also pretended I didn’t strain my left quad on the play and jogged after the ball as it tumbled to the street where we parked the van.

We got going again. I took the ball a bit closer, cut right and not left this time and scored, since Hamza wasn’t trying to goalkeep at all.

It went like this—us maintaining a rough rotation between offense and defense and hoofing after stray shots on goal—until we’d all worked up a lather and an appetite and remembered Mom’s beef tenderloin, which was probably resting on her cutting board that minute, so we packed up and left to feed.

◆

In the spare minutes between soccer and supper, I drank beer. Gina, finished with work, went about creating more work for herself around the house, badgering the kids to clean their rooms, checking off to-do items on a list she kept in her head so no one could assist, even after repeated offers from multiple family members with nothing at all to do.

Not me.

I was on vacation.

I drank beer and wore smudgy gas station shades out on the deck with my dusty feet up on a cloth chair and made myself disappear.

–My shoddy superpower, one of two, the other being minor, temporary time travel ability.

–Which, fed by alcohol, I also employed, and which took me into a new present,

where I confessed random truths to an imaginary interlocutor: I’m afraid to ask questions.

–I believe in spells.

–Mom is lonely, I can tell by the way she walks so quietly, and also because she told me. In her code.

I would go to her with my New York gripes to make her laugh, or spill benign personal secrets that might flesh out the sketch of her now-living-2000-miles-away second son. But then I see her in my mind after I’ve left, and the hole she’s in seems deeper, and that’s not what I want.

So I follow her lead, keep things casual, and make believe she wears not an apron, but a cloak of invisibility, just as she seems willfully blind to all the crushed empties keeping me company.

–All things according to their nature: happy white moths doing their thing as I watch her leave the yard for her little life in her little house behind Hamza’s, and I do mine with the half glass of Indian Pale Ale on the deck above them all, where I am quietly unplugged, and, until Tad returns to my mind, happily forgetting how to read.

All that trip, I found myself in the curious position of being pinned down by a sniper whose primary tactic involved taking potshots before retreating to a fallback position behind his parents’ compassionate blindness to their firstborn son’s mean streak.

Provoke, then wait for momma bear to defend his position—that was the name of the game.

Their hearts were big enough, their vision sufficiently weak, to blind them to an increasingly nasty, nearly six-foot kid, anyway. It all hinged on what Tad knew: the parents were not at home. Not actually.

It was a kind of behavioral pincer move— I could either ignore him and tacitly condone his treatment, or I could strangle him. Rational discourse only led to merciless preteen sophistry and bad faith arguments.

A strange state of affairs, to find oneself ideating the rearrangement of a boy’s face. I wasn’t a monster. The notion was strangely mouth watering though, and to keep myself out of prison, I pretended it was something from a lurid dime novel.

For dinner, there was nothing to talk about.

◆

At the close of that first day—after the tenderloin and red salad, the bottle of sauv blanc and bowls of violet raspberries and cream out on the deck, after walking the dog while the sun submerged in the Sound—we all broke off to relax in drowsy bubbles of personal solitude before bedtime.

I rolled a cigarette in the backyard, where all the scattered toys and balls had the late dusk resembling a hastily-deserted circus ground.

After all the excitement, my skin seemed to give off thermic waves. An overworked V6 finally allowed rest came to mind. How it fumes and drips and sighs as it reacclimates to itself and the surrounding world.

A breeze then, just a whisper, its gentle brush cleansing my mind of what I never realized had been festering there all day long.

There goes my psychic whiplash, I thought. There goes my tongue-bit umbrage, my dark wish to see Tad pulped.

Caught in the current of a soft wind barely able to make the hemlocks flinch, off went all of my ire, like a clutch of tired weather balloons toward distant power lines.

The back door opened and out came Tad again with his soccer ball. He unzipped the safety screen of the backyard trampoline, clambered on, started bouncing and, when the timing was right, kicked the ball against the mesh.

The wheeze of the springs and the ball’s soft thudding were sort of pleasant, made the night less forlorn to me as I smoked and let my brain become marmalade and my eyes cross into a satisfying blur of cool colors.

“Oh, and just so you know–I’m bisexual,” Tad said between halfhearted kicks.

“Oh,” I said, blinking in the dark.

“It’s not a big deal. Our family is so liberal and everything?”

“That we are…”

“Yeah, can you believe Barça traded away Messi? ”

“…Dunno, Tad.”

“Like, what were they thinking? I mean, sure, he’s getting old. He is pretty old now–let’s be real. But how’re you gonna do that to the greatest player of the greatest, like, most popular sport ever?”

“Right?”

Tad leapt higher. I felt a shift in gravity between us. As the kid trampolined in the night, his revelation carouseled in my mind, too fast to get a fix on.

None of it added up. But as I sat there in that polyester lawn chair, as if by some karmic jiu jitsu maneuver, it became a good day. I had been the dastardly villain throughout it, slinking from one cloud’s shadow to the next, wholly unaware he meant something to someone. I glowed with an odd warmth, and I wanted to hug my nephew.

But he kept on, now grabbing big air—Tad, the perpetual motion machine, casually bounding over the moon, the amazing space cadet who never told me I was the last to know.

◆

I shouldn’t have come, I thought to myself, huffing a smoke outside at 4:30 am after rereading Gina’s 4:28 am text message: guys, can we meet at granny’s house for a quick talk at 9:30?

Sounds good!

I smeared out the cig and crept back in to sleep.

We—Mom and I—have been indelicate in our treatment of her son.

The one upon whom I had been too hard, too much an ogre. I’m always somehow too something to someone when it comes to her, him, degrees of severity.

Once upon a time, Mom’s house was a garage no one needed. Hamza converted it into a cute little teal cottage at the back of his and Gina’s property. It was the best of both worlds, in that Mom got proximity to the grandkids and out of Illinois forever and Hamza and Gina got a built-in babysitter and erstwhile cook they could call upon at whim. In this respect, they were simpatico.

I got there early to shower and down a coffee.

Gina was a cyclone of bright blue, summer dress energy when she entered and took a seat across from me and Mom to simply mention Tad was cutting himself and sending nude pictures to strange men on Reddit and contemplating suicide more and more and please can you two give him some slack. To bring up my absent younger brother Nawaz’ childhood, his reclusion, his rebellion, his pot, his hurt, as if we didn’t know, weren’t there, and to say she didn’t “want that for Tad,” as if, somehow, we did.

We sat there.

I listened as she ran down a list of happy words to define him, my head low and bobbing in polite assent, until allowed a chance to say the magic words: “I’ll do better.”

Mom echoed the sentiment, but the fracture in her voice was clear and deep enough to make my own throat ache.

Gina’s too, perhaps, who flitted out the way she’d come in. No chance to retort or explain; we just began loading up the van with groceries and our baggage.

The box was checked off. The road beckoned.

◆

I spoke little the first couple hours of the ride, feigning sleep in the front while Hamza drove and Gina led a game of Mad Libs with the kids and mom in back. Though Hamza took the longer, more scenic route solely for my benefit, I chose to simply imagine all the lush beds of deep green daggers safely behind tinted lenses, shut eyes, and the nagging shame of a spoilsport.

It wasn’t until we were well underway, the Mad Libs booklet returned to her purse, that the content got adult, Tad began questioning Gina, and Gina began to question me.

“Uncle T, remember when that one girl punched you in your eye at work and you lost a contact? Or you cracked a molar or something? Haha, was that the same girl…”

Dredging up this or that past embarrassment while leaving a single detail strategically misplaced, Gina played the naïf. She was baiting me into playing the jerk loose cannon, the wet blanket, or the lowlife, which would give her what she wanted—not the actual story: dominance. But such aims were entirely off-brand.

Momma Bear.

It was a power play and a bum out.

Everyone is her child these days, I reasoned. My life: a joke she couldn’t tell without me providing the punchline. No.

With sharp, one-word responses, I cut her off at the knees. A simple no was my lone weapon, just a little keychain dagger no that Gina felt the need to confiscate lest such a dirty word prick her baby boy. With that, I feigned interest in the fields of verdant alfalfa and peach groves glistening with Cascade snowmelt that irrigation systems pumped and emitted in fine sprays. An apple orchard here and there, set back from the highway as we plowed through the Yakama reservation, where the diners—The Branding Iron, Miner’s Drive-in-– seemed imbued with greater authenticity to our city-slick eyes.

We made a pit stop at a market Hamza and Gina had once been to, marked by a big plastic grizzly revolving on a flagpole. Mom bought a bag of local cherries before the gnarly heat and dry gales drove us all back to the car. I roamed past all the gross fruit and found some gourmet barbecue beef jerky in a clear cookie jar beside the makeshift register. When Tad saw it in my hand, he snorted.

“Nice jerky, dork,” he said, walking backwards to the van to catch my reaction.

But he was grinning, so by Gina’s rules, that made it fair play. The thermostat read 102°.

◆

High desert for miles in every direction.

The Prineville Reservoir was too low to launch boats from any dock, since the drop to the water was now a good fifteen feet. Renting a boat, our whole point, was out.

There was glum talk of paddleboarding, kayaking and more, but the energy wasn’t there. We settled for swimming in the emerald muck.

If taking a dip in a warm kale smoothie sounds refreshing, then it was nice.

It was empty, at least. Though the dark mud was soft and warm as half-cooked cookie dough, and despite my losing a sneaker in the sludge, the damselflies and little dead fish were what broke us and made us pack up and trudge back to the rental home, where each of us rinsed clean our filth-caked feet with the garden hose before entering.

Next day we drove into Bend, strolled the hip shopping district where Mom bought a pair of sandals and I drank beer and gobbled down florets of fried cauliflower in a well-groomed garden overrun with immaculate dogs and their chic young masters.

I kept myself at a remove. I assumed the attitude of a captured ice bubble.

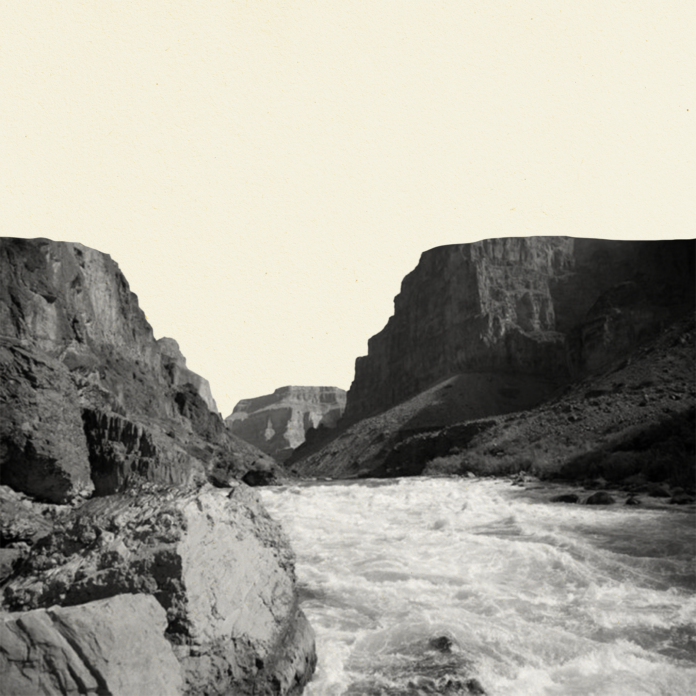

Later: a lazy river on a cold, late morning adrift in a tube, a circular discussion of whether to brave the upcoming rapids or try steering clear of them by hewing close to the left bank. A circular discussion that was ongoing when the rapids hit and we all went down them, whether we liked it or not.

Then it was time to leave.

The return drive was more amiable, as the scrubland beyond the window again turned verdant and we descended from the high desert. The calm was the sort that follows a minor calamity one escapes unhurt. But calamities always came out of nowhere, and we were in nowhere’s dead center.

“I was um raped a couple years ago, you knew that right? By Gunther Vandevelde, one of my classmates?” Tad said, between mouthfuls of Cheetos he refused to share with Jin.

Everyone was quiet.

Gina, sitting in front of me, coughed.

“Tad, let’s not…” she began, then turned her blushing face to mine. “I’ll fill you in on that later. It’s–complicated…”

Of course, that wouldn’t happen.

After flashing a sympathetic wince and stuffing headphones in my ears, I let black metal soundtrack the valley’s evergreen cliffs racing just past the guardrails. Another night of radio silence hounded us toward a pell-mell horizon and the place we’d been living for a long time now, or at least longer than anyone realized.

◆

I thought to wake the house up with Slayer. Pump up the volume. That vibe soon dissolved, though, upon further reflection. Something was off and quickly growing worse.

My heart had a hangover.

It started small as a pinhead, like all black holes, and commenced to devour me over the course of the morning and afternoon. For the first time in days I found myself completely alone for a good eight or more hours. Tad was at chess camp, Jin at band camp, Hamza and Gina at work, Mom on some shopping adventure.

I wasn’t furious until I was.

I circled this fury of mine, seeking a way to ignore it, snuff it, or unleash the thing onto the world.

Soon I was sick of my own head.

Roaming into the kitchen, I perused the pantry and drawers, where there were no sharp knives anymore but that was immaterial, since I found just what I’d hoped, and put the kettle on.

Gina’s bag of poppy seeds sat far in the back, behind the corn starch, unopened and patina’d in pantry dust, but that was just fine–the seeds seemed to glow off blue through their glassine window. Thus they were as yet unwashed, and thus I could say without wholly lying that I did a bit of laundry while everyone else was away.

I poured a couple cups of seeds in a mason jar, filled it with hot water, added in a squeeze of cut lemon. I sealed the jar and gently shook it. After straining the mixture into one of Gina’s bone china teacups, I was sipping off blue cloud water in no time, everything became clear, and I felt good to go.

I was listening to a too-bright sun, primed to hit the warpath, envisioning what would proceed–what must proceed, if I ever wanted to look Tad in the eye again. So:

—When Hamza comes home he wonders what I’m doing, sitting alone in the living room.

—I tell him to go round up Gina. She asks what’s going on and I repeat myself in the voice they never knew I had.

—I tell Mom to watch the kids, us three are picking up pizzas for din din.

—When Hamza tries buying time with reasoned discourse I shove him in the face, ride its registered shock out the door, with muscle he never knew I had.

—I lace my boots up tight.

—I order them both into the car.

—It’s her and Hamza in front, me in the back, me in the mirror. I murmur to myself,

“How’d vacation go, sport? Oh, it was super! Ate a lot of good home cooking, hmm what else? Played a bunch of soccer, a ton of chess, rode bikes a bit, learned my nephew was raped a couple years ago, all in all a terrific week away!”

— I tell Gina to punch in the address I have scribbled on a receipt, for Hamza to abide by the speed limit.

—“…There is really only one job a dad has–protect his young.”

—He’s mute. What else to say?

—I knot a black bandana across my face.

Maybe it was my destiny towards which I made my brother drive us. I did not care much either way–one of our cubs was in trouble and these two yahoos were happy to hold a premature burial. I was flying home tomorrow morning, wearing a stranger’s shoes.

I’d been holding fire, patiently amassing a rage stockpile for years, one reserved for someone who actually, truly deserved it.

–That’s what I tell myself, as block after block fades behind us.

–“Turn up the music,” I say, the hardcore ripper I make Gina play. Not because I am a tough guy–I’m not. Because I am scared. Anger burns it alive.

When it comes to violence, ability is less material than a willingness to get stomped over a principle.

“I’d rather be pissed than frightened any day of the week,” I say. “I’d rather Tad knew his dumbass uncle gave a care and tried than that he caved in, afraid of consequences, of a possibly prison-bound life for rightly doing what needed to be done. Maybe jail’s where I belong. Maybe that’s fine. I’d rather have no future than no soul.”

The shade trees lining the street make us flicker and freckle at random but I’m not trying to read faces anymore. I know they think that’s corny.

“Tadeen is now a boy forever swimming in adult waters. And you two just let it happen,” I say.

Hamza is sweating through an awful smile.

“Where is the lawsuit? The police report? The Seattle Times coverage? The torches, the pitchforks? Oh my god, you goofy schmuck, you knob! Why is that kid’s, and that kid’s dad’s, head not mounted on the kitchen wall right now?”

I’m screaming. Hamza sits there and grinds his teeth, wishing the light would change. Gina quibbles and I go shh.

“Park at the far end of the block, keep the engine running or kill it, I couldn’t care less.” I’m already storming up to the door.

It was always either astronaut or vagabond when it came to what I wanted to be when I grew up.

I ring the bell, wait, rock on my heels, and when the door opens, I ask: is this the Vandevelde residence, is Mr. Vandevelde is in; when they ask who I am, I say my name is John, I’m with Concerned Homeowners of West Seattle?

Because I figure that’s what a bad guy would say before doing all the bad things he comes to do—before I say hello Mr. Vandevelde and: break his nose before he can reply, crush his larynx with a knee as he’s doubled over, wild out on his solar plexus and groin with my boot heel. Before I hurt him worse than I’ve ever hurt anyone. Maybe he’ll understand, maybe he won’t, and maybe his wife will see, and the boy, and maybe I hope they do.

When I finally show them all just who I really am.

When the front door knob turns, my hand even forms a fist, all on its own. That’s all it takes to shatter the whole thing.

Mom struggled through the door, arms hung with plastic shopping bags. Seeing me sitting there, seeing her face fall–something was exchanged in the air between us.

All I could say was, “Why didn’t you tell me?”

She spoke but I didn’t hear much. Later all I recalled was her sadly shaking her head. But that pretty much summed things up.

I stumbled into the backyard–my backyard, fell into my polyester folding chair, and smoked around a thousand cigarettes back-to-back, between tart nips of leftover sauv blanc from the other day and repeated self-commands not to crush the wineglass in my hand.

I tried to locate the best, or better, part of myself. The forgiving, reasonable, generous part of me that had reliably gotten me through so much. But it was elusive.

That guy had all of a sudden grown shy.

Like diving for a lost swimming partner, pinpointing my better nature only kicked up murky, despairing clouds. My mind flailed in a misshaped circle.

Then, to my left, in the middle of the driveway, there appeared a rabbit.

Its hind legs were the gray of old firewood and long like the runners of an upturned rocking chair.

It sat in full view and sniffed the afternoon air. I rose as quietly as could be and tiptoed backwards inside, where I then broke into a sprint, yelling to everyone that there was a bunny rabbit outside.

“Oh, damnit!” Mom said. “Get rid of it, it’ll devour my new garden!”

“Get the dog!” someone hollered.

The dog. Bluto, who, one afternoon last summer, had paralyzed an alley cat by rag dolling the thing with a brutal glee.

Get the dog.

I skipped steps running downstairs.

Outside, the rabbit, exactly where I’d left it.

It was about to bolt. I needed to buy a few seconds before the cavalry came.

Picking up a dodgeball, I took quick aim and pitched it.

I hit the little guy square in the forehead; it reeled in a seized daze, then it quivered a bit, before finally regaining some of its faculties.

That’s what made me the bad guy. Sorry, little dude.

“Bluto, kill! Kill, Bluto!” Someone screamed as they all burst outside. The dog appeared groggy and confused at first.

“Bluto, look alive!” screamed Mom, pointing at the rabbit, who, having caught the dog’s scent, took off for the garden. The dog ripped across the lawn in chase.

They met at the fence, where the rabbit tried burrowing into the mounds of mulch that marked the perimeter.

I couldn’t look. An ensuing growl and frightened squeak made me wish I could plug my ears too.

But when I opened my eyes, I saw the dog paw at the rabbit, sneeze, then glance up at me, as if to say, wait, this is no cat…

“Bluto, what’re you doing? Kill!” Hamza yelled, and laughter exploded all around.

But the rabbit and dog stayed where they were. Very soon, they were both promenading around the fence like ice skaters collecting crowd-thrown bouquets, fast but best friends, and lifelong homies by the time they reached the concrete driveway.

Bluto kept near the rabbit, like a protector.

“Bluto, you’re useless,” Tad screamed, marveling at this unusual alliance.

Tad. Weirdly, the only one of us brave enough to voice what was going on. The only one to let me in, when as a matter of general policy, everyone else had closed up shop.

“What just happened?” he said. Having had the words taken out of my mouth, I simply gave a maniacal grin and put him in my most loving headlock. To express her general approval, Jin did cartwheels, and Gina caught a photo with her phone.

Mom, broom in hand and with due tenderness, swept the rabbit toward the chain link gates that led to the back alley. With her hips, she boxed out Bluto and gave the rabbit one last gentle sweep toward the gap in the gate.

Once out, it briefly looked back at us. In its expression, a familiar sort of unkind amazement. That which, for so long, had us all in its jaws, before we figured out the fine, forked over what we owed, and were issued this temporary clearance.