I know myself in relative terms. The sun is yellow, as am I; her blood is red, and so is mine. This time of year the air is cool, and I am cold; here is my garden, leather spread by goosebumps.

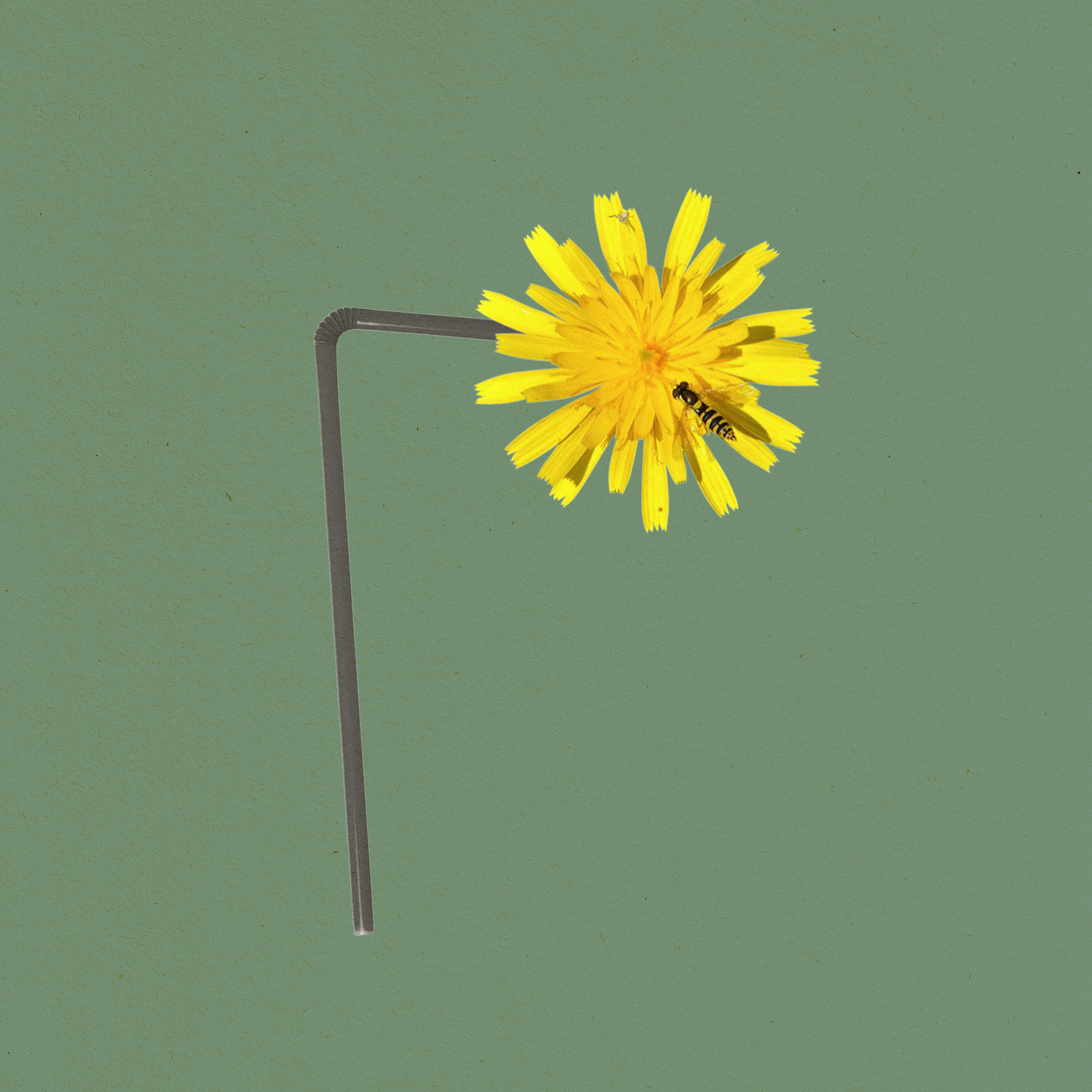

Here is my garden of dandelions, which in the summertime grow between the sidewalk’s slabs of concrete. My building’s front steps slope down alongside them as if water logged, and beside the molding staircase is the mulch my landlord planted in lieu of grass. Its rot serves home for the worms; wet dirt seeps up from between the shavings. And here in the street my garden is the thistle I pass on early afternoon walks, and the sunflowers nobody planted on the side of the road, which press up against storefront windows and stop signs. Here in my bedroom my garden is the window’s view across the back alleyway, where my rear neighbour is growing a deranged collection of herbs on his balcony. I overheard him once say that he wishes he could plant an avocado tree, but the climate is too cold even in the summer months. He described the way that they decay from the inside out—rotting from green, to brown, almost to black, until they match their skin’s colour—he said, “brown is the colour of their death.”

Here—(I am clutching its scalp now)—my garden is the hair on my head: matted in the mornings if I’ve forgotten to sleep in my bonnet; smooth and dewy after watering; brittle and dry by evening-time. Its tendrils grow slowly regardless of thought or conditioning.

I think aloud, my skin is brown. It is brown and yellow and black; in the winter I turn a sickly sallow because I don’t go outside. I cannot change the colour of my insides, and would not know if they were brown like dead avocados or white like mold if I could not bleed. Here, my insides are my garden—see, I’m clutching them now, squishy and soft like ripe tomatoes plucked fresh off the vine.

In the autumn months I’ve seen my rear neighbour on his porch, observing: the leaves crinkling between my toes as I cross the length of my apartment’s floorboards; the yellows and oranges and reds of the hardwood so saturated they are almost moist. I open my windows to see the wind rustle them. I watch the alley cats weave between fence posts and water weeds with their urine. I watch the rain join the potholes to become puddles, and rubber boots splash through them in a rush.

Here, in the mirror so clear it is liquid, I watch my garden. On its cheeks a flush of roses peer through melanin, a dirt of my own.

◆

I thought I witnessed something but I couldn’t be sure. On the morning in question I opened the street-facing windows, as I do every day, to listen to the crows. Brisk winter seeped through. I watched it shiver and my eyes saw my toes go from yellow-brown to blue against the kitchen’s tile floor. I looked out beyond the front steps, slick with ice; I looked beyond the frozen mulch and the snow banks at the side of the road. I watched the bicycle riders that somehow never slip, the cars parked and buried, and the naked tree branches cracking under gusts of wind. My garden is a frozen landscape bustling, bursting.

I watched the boots trudge through snow still falling, not yet shoveled at the early morning hour; their noses rouged much like my own, tips of ears exposed and already bitten. I noticed my rear neighbour among them, standing as still as the car he was leaning on, smoking a slow cigarette and watching the people on their way to catch a train. His knuckles were trembling slightly. I saw the dirt under his fingernails and a tiredness under his narrow eyes; his lips were pale and thin. He was watching the people: he watched a child step off the sidewalk— purple mittens, a red tuque and grey jacket, tiny backpack slipping off her shoulders, skin like mine; perhaps a kindergartener on her way to the schoolhouse down the street. I wondered why a child was walking by themselves but decided that she probably does it every morning. I watched them both, as I’ve watched countless others.

If my phone had not rung at that precise moment, perhaps I would have seen it occur, perhaps I could have done something. But on the line my mother asked how is my garden. I told her it had seen greener pastures. The air is cool and I am cold. She called me by the name she gave me and we talked. She said she knows this time of year is hard for me; she asked if I’d called my father, and I watched my garden. By now the child was walking on the road where the snow was not so deep; she was dragging her purple mittened hand through the frost on the sides of parked and buried cars, making a trail that followed her. My mother asked again how is my garden and I said it was fine. She suggested I go for a walk. I was too tired to argue, and agreed.

I exited the backway into the alley, to bypass the slanted and unsalted front steps. My rear neighbour’s car was still in his driveway, buried—I wondered, for the second time, why he’d been smoking below my front window. I wondered if he’d seen me see him; I cleared it from my mind. Here is my garden, bundled under three sweaters and a suede jacket, a woolen scarf and olive green gloves. Here is my garden, frozen potholes and chain-link fences coated with ice, squirrels scurrying across them, a dog’s paw prints leading away from yellow stained snow. Perhaps it sniffed this garbage can or carried that large stick in its mouth.

I turned the corner and stood across from the schoolhouse; I hear its bell ring every morning, every noon, every afternoon at three, though I hadn’t heard it ring yet this day. There were no shrieking children or sounds of laughter; the street was empty—there were no bustling boots on their way to the metro station. Here is my garden, pure white and desolate. My rear neighbour gone, the kindergartner, gone too. I wondered about which cubby she uses to store her winter boots in school, whether she ever gets her socks wet on the hallway carpet before switching into her sneakers. I avoided the sidewalk as she did: walking on the road towards my front door I came to where I last saw her, and I knew it was so because the trail from where she came ceased there—small footprints that faced me were stopped in their tracks, purple mitten’s trail along car windows ended abruptly. I wondered if she’d crossed the road there, and perhaps those footprints blew away.

Here is my garden: white tapestry draped across everyday things, cars and jackets’ hoods and gravel and dirt and mulch. Any colour stands out starkly; and there was purple mitten on the ground. I picked it up, and there was little name written in pen on a homemade label, “Heather.” And there was little blood stain still wet on the edge of it, and there was matching blood stain on the car window. Here is my garden, plump red berries dripping off of white ice.

I hadn’t known ice could be sharp enough to cut flesh, but sure enough it is. I thought of bringing purple mitten to the schoolhouse lost and found, but worried Heather would look for it here after class. I brought purple mitten home and remembered to watch the window when the afternoon bell rang.

Here is my garden, cool timber floors the colour of autumn leaves, smooth beneath thick and slippery socks. My curtains wide open to the white light of winter outside. I thought of Heather and hoped she got a bandage from a teacher. I watched my garden from the bedroom window; I saw my rear neighbour’s car still in the driveway, sleet-covered, untouched. Perhaps he took a snow day. I wondered for a third time why he was smoking beneath my front window. I saw his curtains open then and I tried not to look inside, before he approached the glass, looking out across the alleyway with darting eyes; seeing me, and I seeing movement behind him. I supposed he had company. His pale palms looked almost red, probably blood rushing back to cold hands. He shut the curtains with such force that they swayed, and I caught a glimpse of something on the windowsill that shouldn’t be.

◆

My brother has purple mittens, and so does one of my professors—it would be too much to think too much of a purple mitten on a windowsill. Perhaps I imagined it. I thought of my rear neighbour; I thought of when I’ve seen him watching me through my bedroom window as I compulsively cross the length of my apartment, back to front. I watched my garden: an uneasy breeze whistled through a crack in my window pane; rustled leftover dead leaves sticking out from between bits of ice on the alleyway’s concrete. I thought of calling my mother and confiding in her, but decided against it.

I do not know what I have seen. Probably nothing. I watched my garden: worry lines gathered amidst my forehead’s gradients of sallow yellow-brown. Here is my garden, brown and yellow and black, overtired eyes and furrowed brows.

It is not relevant, but I ate a peanut butter sandwich and sat by the front window to read. Rather, I tried to read, but could think only of the bell ringing around three. The sun crept across the sky from left to right—I waited. And when the bell rang, I stood up, abruptly. Surely she would appear, crossing the street and heading back the way she came that morning. I was sure. I was trying to be sure. I waited, I watched as countless children crossed the street and headed in every direction. I tried to remember other details about her—purple mitten, at least one, surely; red tuque, I thought, and grey jacket. Heather.

When she did not appear, and the crowd of children dissipated, I thought maybe I’d missed her. I considered waiting until the next morning to see if she would take the same route, but I couldn’t decide what was more naive or paranoid.

I thought, maybe I’m projecting. I only know myself in relative terms: the sun is yellow, as am I; her blood is red, and so is mine. I shouldn’t know what colour her blood is. But here on purple mitten there is evidence, as much evidence as I have of my own red and sticky insides. Here is my garden: red and sticky and vulnerable like a child’s. I tried not to think of it. I’m just projecting.

I retrieved purple mitten from where I’d left it and exited my apartment for a second time. Here is my garden, vast as the sun setting before 5PM: music playing in some nearby apartment, frozen telephone wires criss/crossing across the alleyway, between the tree branches. I stood, for a moment, facing my rear neighbour. His car was still parked and buried; if he’d left the house, it was on foot. If he was home, I hoped he couldn’t see me standing there. The weather had thickened—the snow was no longer drifting gracefully from the sky, but falling straight down, heavy as rain. All I know of him is his feelings about avocados; I know he lets his garden overgrow in the summer and in the winter he leaves it out to die. I headed for the schoolhouse.

They leave the doors unlocked until four. I don’t know how I know this, but I’m sure enough it’s true. A janitor was mopping the floors when I entered. I paused on the doormat and apologized, stomping the snow off of my feet; he waved a hand at me indifferently without looking up. It shouldn’t be so easy to just walk into a kindergarten.

I went in the direction of the office. I passed cubby walls and classrooms: here is the kinder garden—there is the carpet where they sit to read; a box of toys and stuffed animals; blocks; groups of small desks with still-warm silly puddy left to dry on paper plates. The hallway walls were lined with brightly decorated bulletin boards and posters; some of them told me which way to go, and others, to believe in myself. I wondered if the two were related. I tried to remember what the walls of my own kindergarten looked like but could not recall the memories; I cleared it from my mind. A smiling yellow face told me to turn left. I’ll drop purple mitten in the box, I thought, and go home.

I wasn’t expecting to see her at the end of the hall, sitting on a bench beneath the lost and found sign. Grey jacket, red tuque. One purple mitten on. Her boots looked a size or so too big and dangled several inches above the tiled floor, swinging against any discernible rhythm. She was reading a well-worn storybook—La Famille Berenstain—and picking her nose with her left hand. From where I was standing I could see the edge of a bandaid stretched across her palm.

I could feel myself staring and clutched purple mitten in my pocket. I knew if she looked up she would see me. She hadn’t, though, and I was about to walk towards her and smile politely as one does with a child, and I was going to tell her I found this mitten on the road outside the schoolhouse and does she know a little girl named Heather who lost a purple mitten? And she was going to say that’s my mitten! And I was going to say what are the odds! Here you go.

Before I could take a step, though, her mother appeared (she looks like her). She greeted Heather with a kiss on her head, and then one on her bandaged hand. She helped her daughter off the bench and they crossed the hallway to descend the stairs.

I was only standing there for a moment, but I feel as if I have violated something.

◆

Here is my garden. It is a collection; it is how I put pieces of the world together, or so my mother says. Here are some pictures of her and I. And here are the dried dandelions, I keep them pressed between this book’s pages—I found them last summer between bits of the sidewalk alongside my building’s front steps. Here are some scraps of mulch and some thistle, a sunflower petal; here is the view of my neighbour’s balcony, where he grows a collection of herbs. He wants to plant an avocado tree, but the climate isn’t right for it. In the autumn the air is cool and I am cold.

My skin is brown, sometimes like the insides of dead avocados, and I know what colour my own insides are because I’ve seen them, or their blood, anyhow. I don’t like to think about it and try not to dwell. In the wintertime I am suspicious of everything, I don’t usually go outside; but when I do I am struck by the ever-shifting stillness. Right now I am walking home from the schoolhouse and I feel it in my stomach; I am not sure what I should have done but I don’t think I have done it. Here is my garden: cold and crunchy and soft all at once; sharp enough to cut a child’s hand. Dry and wet, heavy and light, and bright, but dreary, and full of life. I cannot trust my own perception.

In the alleyway my rear neighbour is standing in the space between our buildings, facing mine. When he sees me, he waves. I feel it would be more strange to turn back now, so I continue on obligingly. I clutch the purple mitten in my pocket. He says my name as I pass by and I nod and smile politely; he says, can I ask you something? I stop at the base of my fire-escape’s stairs, face him. Say “sure.”

He asks if I’ve been watching him. I don’t know what to say. I settle on: I mean, I’ve seen you. We are neighbours afterall. You have a garden. He puts his mouth in a line and nods. His hands are bare in his pockets.

I ask him: And you? Have you been watching me? He seems surprised by the question.

We are neighbours, afterall. You keep your curtains open all day. You don’t leave your apartment much. And you pace a lot.

He shifts uncomfortably. I don’t know what to say. Okay, I say.

Why were you watching me today?

I don’t know what to say. I take the purple mitten out of my pocket and hold it in front of me. I don’t know what I’m expecting him to do but I want him to take it: I don’t want this in my garden; put it in yours. I thought it was yours, I don’t know why but I thought you did something bad and this was a part of it; I don’t know why I took it into mine.

Did you knit this? It’s good. You should make a pair. I could really use them.

I wonder about the mitten I saw on his window sill. I probably won’t venture outside again for several weeks. This time of year the air is cool, and I am cold. Here is my garden: bare hands, leather spread by goosebumps. He hands the purple mitten back to me. I’m going to keep it behind my own shut curtains so I can’t see it; Here is my garden—red and sticky insides, brown-yellow-black skin.