What I didn’t know about Justilien Gaspard when I heard he was dying alone in Mexico was that he was gay. That he was the son of a Jehovah’s Witness who had been disowning him, off and on, for years. That his mother, with whom he had been close, had committed suicide a few years before.

I didn’t know how the events unfolding over the next days, weeks, and years, would pull me in. How I would attempt to repatriate Justilien’s ashes in a wooden box, and would end up wrestling with the puzzle box of Justilien’s life instead. How everyone who ever cared for Justilien could do little for him except possibly to try to understand him, to find the levers in his puzzle box and marvel at them, to remember him as he was.

Going in, what I knew about Justilien Gaspard was that in high school, he had been cute, with floppy blonde hair parted down the exact center of his head and a shy demeanor. He wore a camera around his neck everywhere he went. And one boozy night in Natchitoches, Louisiana, on the banks of the Red River, he taught me how to say no in Russian.

Nyet.

We were high school classmates at a public boarding high school in Natchitoches, at a place that provides college-style classes for high school juniors and seniors.

Anyone that you see at breakfast, and lunch, and dinner, anyone that you take classes with and hear rumors about and bump into when you don’t want to be seen and who maybe might catch you doing something you didn’t want to get caught at – all those people, you’re going to have some kind of relationship with. But Justilien had never been someone I knew well, someone who might share my secrets while whispering outside my window or on a Friday night stroll to the cemetery.

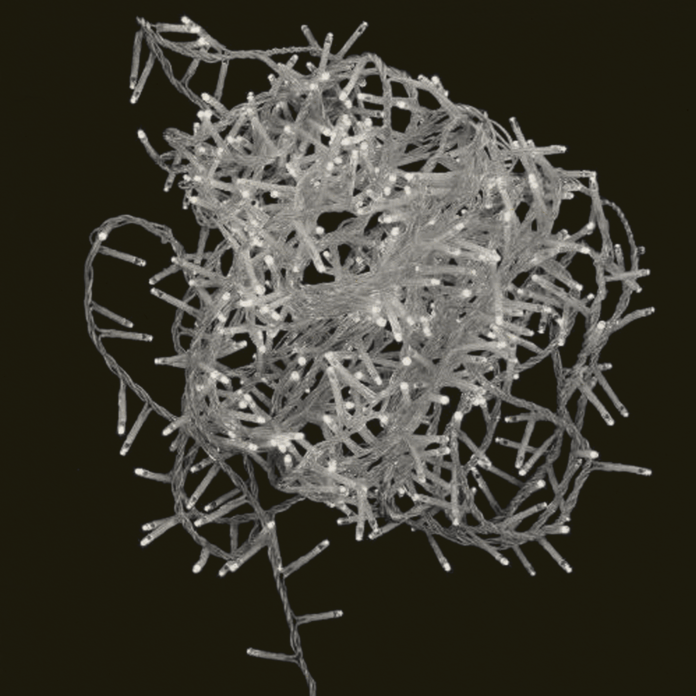

About halfway through our junior year, Justilien and I had wandered over to the Festival of Lights. The town we lived in attracted thousands each year to see Christmas lights strung across the local river. As high schoolers, it was an easy place to get lost in the crowd, eat a funnel cake, maybe drink a beer. I wondered if he might try to kiss me. We had somehow procured Zima, the White Claw of its day. I don’t remember having many feelings about maybe kissing him as far as Justilien the individual was concerned. He had that hair, a sweet smile. His photography was black-and-white only, which meant he was arty — a plus in my book.

My first boyfriend had broken up with me just before I came to the school, and the experience left me feeling shaken and unsure of dating in this new environment. As far as I could tell, my role was to be open to all comers and then, if the guy tried to kiss me, to get back to the girls’ dorm as soon as possible to crow about it.

Of course, I could dislike a few guys, but it was always unclear to me what the disqualifying grounds were. And there were some strict social rules: you didn’t kiss anyone that your girlfriend had just broken up with, for one. I didn’t have many girlfriends, though, so that possibility didn’t come up much.

Justilien seemed as good a prospect as any, and while I wasn’t excited, I wasn’t not excited either. But he didn’t try to kiss me. He tried to teach me Russian.

We sat there, on the clay banks of Natchitoches’ Red River, anonymous in the crowds stumbling around us, nothing but the twinkle lights of angel wings far above us for light, sharing bottle after bottle of Zima. Justilien was taking a class in Russian language and history; unprompted, he started speaking with great passion about the great depth of the Russian character, the astounding perseverance of their national history, their fascinating language.

We walked back towards the dorm in silence. Wrapped in my own drama of my inability to get a date, I assumed Justilien didn’t like-like me; that was as far as I got. If my roommates had asked me if anything had happened, I might have shrugged and answered, “nyet.”

I hadn’t thought to wonder why a nice, quiet, artsy young man might get me tipsy and then start a Russian history panic-lecture.I thought very little, if at all, about Justilien after graduation and for another 20 years, and the same was no doubt true in return.

Justilien eventually went to the Rochester Institute of Technology, then started his own small technology company. I eventually became a librarian and moved to Washington, D.C. Our lives, never particularly close, diverged further. Had he not died the way he did, I might never have thought of Justilien again.

I watched his death unfold on Facebook. A stranger named Timothy reached out to the school’s Facebook alumni group. The man said he was a friend of Justilien’s and also a pastor. He asked, “Have you heard from him? Has anyone talked to Justilien in the past 24 hours?”

Timothy claimed that Justilien was desperately ill in Mexico, and had been ill for some time.Justilien’s aunt joined the conversation. She said that she had received a thumbs-up emoticon from Justilien, but that he had been too weak to talk on the phone. She hadn’t heard anything since.

Who were these people? I wondered. Why were they on the alumni page?

Timothy reassured the aunt, said he’d try to find the owner of Justilien’s apartment building. He said he’d find someone to check on him.

“In Mexico?” I thought. “He’s going to find someone to go check on Justilien in Mexico?” But I didn’t say anything. These people, whoever they were, seemed to have the situation, whatever it was, under control.

But the next day, Timothy returned to our Facebook group. He told us that Justilien was dead, that Justilien had died of dengue fever.

Almost no one dies of dengue fever – no one, that is, who seeks medical care. It sounded so crazy, the alumni group split and formed alliances. Some believed our classmate had died, but many believed Timothy and the aunt were husksters, fishing for sympathy and, inevitably, money. We were a fairly tight-knit group, having lived together for two years, and wary of outsiders. While it was true that no one quite knew where Justilien was, how likely was it that he was alone in Mexico, and had died there, in his 30’s? Finally, someone who lived in the Buffalo area, where supposedly Timothy lived, drove out and had an in-person meeting with him. He was real, it turned out, and so was the news.

Justilien was dead, and he had died alone, in Playa del Carmen, Mexico.

There was the death, and then there were the problems, most pressingly: what would happen to Jusilien’s body? Justilien had been close with his aunt, who lived in Louisiana, and she wanted his body or his ashes returned to her. She was not, however, his next-of-kin.When an American dies abroad, the State Department may assist with having the remains shipped home to the next of kin. One problem: Justilien’s father — his next of kin — kept changing his mind on whether or not he wanted his son’s ashes back; whether or not he would have anything to do with his son.

He would push a lever, and a possibility would slide open. He thought again, and the puzzle box would close so cleverly, you would never guess that there was an opening there in the first place.

I’ve seen the letter, or a copy of it, that Curtis Gaspard, Justilien’s father, first sent to the State Department, asking for his son to be returned to him. It asks that “Justilien Christopher Gaspard be cremated in Playa del Carmen, Mexico and his ashes and belongings be transported back to my possession in the United States.”

Curtis signed it and included a photocopy of his driver’s license. He also included a copy of a picture of a woman labeled, “Wife Margaret at 59. Now 74.”

At the top of the letter is a hand-written note, “Amy Office Depot checked 3 times to make sure it WAS received.”

On the strength of this letter, a funeral home took Justilien’s body and cremated him.

Timothy set up a Go Fund Me, payable to Curtis Gaspard, to help pay for the cremation. Events seemed sad, but accounted for. Alumni donated. And then, the wind blew, as it must have blown many times in Justilien’s life. A lever was pressed. The puzzle changed. Curtis refused to cash out the Go Fund me. He wanted nothing more to do with the ashes, nothing more to do with his gay son. Nothing could convince him otherwise; eventually, the funds were automatically dispersed back to the alumni and other donors.

This is where, ignorant of many of the events that had transpired but with a sense that progress had ground to a halt, I started corresponding directly with Timothy, offering help. I was fidgeting, poking, looking for a way in, a way to open up the possibilities, a way to understand what had happened.

My father had died less than a year before Justilien’s death; perhaps that’s why reached out so eagerly. Maybe I wasn’t ready to let my dad, or anyone else, go so easily.

We don’t know, exactly, what had happened with my Dad. What had started out as his standard mid-winter cough had turned into something much worse in March; by May, the doctors said that there was a shape of some kind in his lungs, they weren’t sure what, but it was too late, he was too weak. And then he was gone. He died May 15th. We didn’t do an autopsy, though doctors may have made mistakes early in the diagnosis. We left that puzzle alone, thinking, “What good would knowing have done? Nothing will bring him back.” He would have hated for us to spend our time in courts, suing for reparations, when ours was the kind of wound that cannot be repaired.

These days, I wonder if we were right. What good does not-knowing do? We destroyed his body, with all its little levers and compartments, all its tender secrets, with his cremation, and now we’ll never know, exactly, what he died of or why. He sits in a very handsome box, made of polished black walnut, on a chest of drawers in my mother’s bedroom.

When I imagined bringing Justilien back to the United States, I thought of the box that holds my father’s ashes, but in a slightly lighter wood maybe, to carry on my lap. You’d be surprised how heavy human remains can be.

I started to put myself to sleep imagining Justilien’s remains, envisioning placing them carefully on the baggage scanner in some semi-tropical airport. Sometimes I imagined it all going smoothly, bringing the ashes back to Justilien’s aunt, and feeling heroic. Sometimes I imagined placing the box on the airport scanner only to have the lid come loose (how was the lid attached anyway? was it a hook-and-eye thing? could I shrink wrap the box?) and scattering Justilien’s ashes in the Mexico City airport. What would I tell people then? I would sit up in a panic, unable to fall asleep for hours.

I had an invitation to the wedding of another high school alumni in Mexico City that November, and I used it to hatch a plan. I could negotiate with the funeral home director for Justilien’s ashes, fly out to coastal Mexico, pick up the ashes, fly over to the wedding in Mexico City, fly back to Louisiana and drop off the ashes with the aunt, and then head on back to my home in DC.

I wrote to my alumni group, suggesting the plan. Timothy had already set up a second Go Fund Me to pay the furious Mexican funeral director who had cremated Justilien on the basis of Curtis’ letter and who still hadn’t seen a pesos for his troubles.

I got back a warm, but decidedly cautious response. I’m sure it wasn’t easy, letting me know how nuts I sounded. So my friends and fellow alumni didn’t, but they did point out that I was still not Justilien’s next of kin. It continued to be the case that, legally, random high school acquaintances cannot show up at a Mexican funeral home and pick up someone else’s ashes — not without a letter from their next-of-kin. And, still, Curtis Gaspard refused to have anything to do with his son.

I began writing the State Department, begging them for an exception to the next-of-kin clause.

I kept writing to Timothy too, trying to understand more about Justilien’s life and who Timothy had been Justilien. How had Timothy known when Justilien was dying? How had he known to about Justilien’s alumni group? How had we ended up here? It felt like running my hands along a perfectly smooth surface and then, yes, a little roughness, a tiny ridge. A catch.

Timothy had been a student pastor at the Rochester Institute of Technology; sometimes, he provided student housing for kids who were in some kind of trouble. Justilien didn’t get along with his roommates, but he couldn’t afford to move off campus into an apartment of his own. Timothy offered to let him rent a room for a nominal fee. Timothy’s wife became sick shortly thereafter, and Justilien had been there the night of Timothy’s wife’s death.

“Justilien introduced me to his strong black coffee, jambalaya and other foods from his home,” Timothy wrote. On the night that Timothy’s wife died, Justilien brought Timothy a mug of that strong coffee. “He was living with us at one of my most darkest hours and got me through the night.”

Justilien later started his own tech business; he also sold tea. He fell in love with a man in Rochester, NY who moved on and left him behind; it’s not clear if he fell in love again. He traveled through Latin America, and called himself a digital nomad. He lived cheaply. He lost his mother to suicide; he started drinking too much. And he got dengue fever twice.

Dengue is a flu-like illness that rarely causes death. However, it can become severe, and severe dengue can lead to death. There are four variants of dengue, and catching more than one variant of dengue makes it more likely that the dengue will develop into severe dengue.

Assuming that Justilien had developed severe dengue, he would have had 24-48 hours to find medical care. Justilien heard from both Timothy and his aunt in these critical hours, both of whom urged him to seek medical care. His own body must also have been sending clear signals as well: symptoms include blood in vomit and severe abdominal pain. It was during this time that he sent a thumbs-up emoticon to his aunt, his last known signal of life.

It may not only have been dengue that took Justilien, Timothy told me. “He struggled with dengue fever, but I learned from his autopsy that what killed him was alcohol abuse.,” Timothy wrote to me. “He told me that he could buy vodka cheaper than clean water at the grocery store.” He laments that, if he had known how bad things had gotten, he would have flown down. He was in the process of getting his passport when Justilien died, a process he has now dropped. No need to travel, without Justilien.

As Timothy and I continued our correspondence, I was also continuing negotiations with the State Department, the family, and the funeral home. It was now summer, nearly six months after Justilien had passed. As my classmates pointed out, even if I could somehow repatriate some ashes, how were we to know the ashes the funeral home would give us would be Justilien’s ashes?

We wouldn’t, that was how. We just wouldn’t. I couldn’t say that though, so I just kept forging ahead.

The negotiations with the funeral home started at $4,500.

The State Department doesn’t give a limit to how much recommended cremations can cost per country, but they give a range. In Mexico, they’re supposed to go up to around $1,000.

I offered $1,500.

The funeral director refused to budge. The alumni who had been with me dropped out. It was too much, they said. We’ll donate a brick at the school in his name.

And then, it was over. I didn’t have $4,500 to give, not to mention the airfare. Without a letter, and without money, I couldn’t go to get his ashes. I wrote to Timothy. He accepted it as God’s will.

I wrote Justilien’s aunt, and she was awfully nice about it. I would have preferred it if she had cursed me out, but she didn’t.

I’ve never been particularly good at solving puzzles, and I didn’t solve these. I don’t know what killed my dad, and I did not repatriate Justilien’s ashes.

I slid my finger around the box though, I found a few ridges in the smooth surfaces of the past, a few catches to press, a few compartments to explore. When I talked about Justilien to the people who knew him, his name seemed to open their hearts. “I remember him,” they say, “I remember he always had that camera.”

When Justilien died, I hadn’t been ready to let him go. “Nyet,” I said to the State Department, to the Mexican Funeral Home, to my friends and classmates, to Curtis Gaspard.

Surely there’s more to learn, more compartments to open, to understand how a Louisiana teen told the truth about himself and withstood great hardship and loved and lost and traveled Latin America. In the meantime, imagine me, sitting on the banks of the Red River, a Zima in hand, toasting the angel outlined in twinkle lights above me. “Da,” I say to him finally. “Da.”