Today my mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer. The first time the nurse took her blood pressure, Ma was sitting down, and it was 148 over 99. Too high. The nurse, Anita, noticed that Ma must have been nervous and stressed out about the appointment, and so she told her to stand up, breathe, and place her arm on a stand aligned with her shoulder. Ma obliged, took a deep breath, and relaxed. Her charts then read as 130 over 44. Better.

It was during this time that Anita talked to me in a low voice, “It’s really good that you came with her today, her daughter. It will be a good talk.” I didn’t know what to make of that comment, so I nodded and extended my gratitude to her. I liked when people recognized me as my mother’s daughter without my saying. I needed this assurance that we belonged to each other. I needed this especially when other thoughts in my mind, the one I pressed down and away, tried to convince me of a future where these occurrences may not take place. I liked the way the nurse repeated my positionality to me, and then to herself. I liked addressing people and addressing one’s self.

◆

On the drive to the hospital, Ma said that she wanted me to go with her because she didn’t want me to say that she didn’t try to tell me when something was going on with her. She had a recent surgery to remove a part of her parathyroid gland this past January, three days after her New Year’s Day birthday, and she told me and my brother about it maybe three weeks prior, a few hours after we had all spent the whole day hanging out. Eight hours, to be exact. We had taken her grocery shopping, shopping for clothes, and getting coffee and snacks. She had all that time to tell us about her appointment.

My mother and I have only recently started talking in a language of intensity and seriousness. These days, I think often about what else she has to teach me, and how my life is infinitely challenged and open to intertwining our lives more and more now that we are both getting older. Now that I have the capacity to be more responsible. Now that she feels like she can ask me for help. I refused to do or prioritize family even when I was a teenager, something I didn’t see a need for when I was in my twenties, and something I am fighting to save with every available second of my thirties. This switch, and this need for a shared language between us, becomes apparent to me–I visualize our time together as an hourglass sand timer. Each grain falling, inching toward an end.

She told me about how she had been menstruating for the past few months, and how her primary care physician sent her to an OB/GYN, Dr. R., who then performed a pap smear, and called her back four days later, on Friday, April 6th, to share the results.

Ma texted me about coming with her to this appointment four days before. I am a new English faculty member at my local community college. I don’t typically have appointments nor classes on Fridays, so I opted to clear my schedule to be with my mother. I would be lying if I didn’t state that I had a feeling that I had to clear my Friday schedule for this particular appointment. I had a feeling that I needed to leave that day undetermined by me. Not only was I exhausted from the work week, I was listening to my body and what it needed––something that has taken me my whole lifetime of thirty years to be in conversation with.

◆

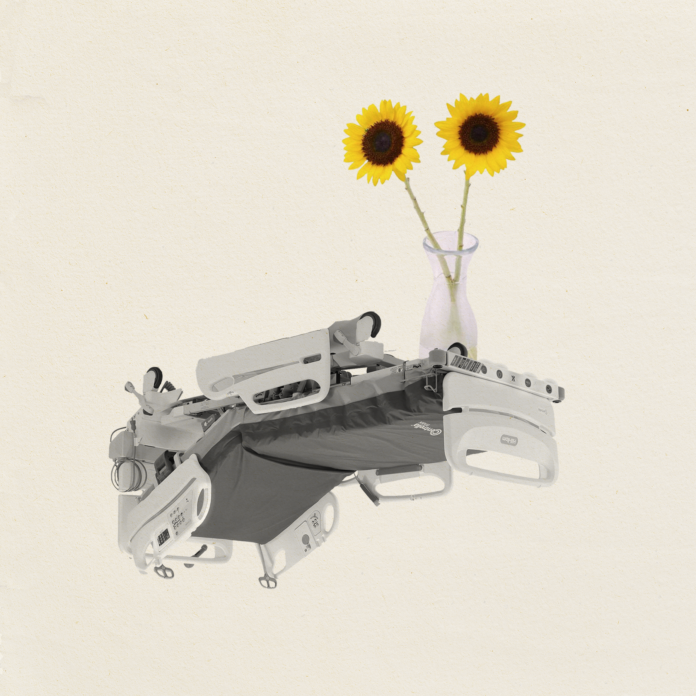

“Oh, see? Normal now,” Ma said, half-smiling at her digital charts that blinked neon green systolic and diastolic numbers. Nurse Anita escorted us into an open room with a white board drawing that I had been staring at from the hallway. I’ve always loved whiteboard art, as a teacher myself, as I like making the extraordinary out of everyday materials. The drawing was about newborn babies and new mothers, and it illustrated a large, yellow sun with two sunflowers, one short and one tall. It said something like, “Newborn babies + new moms = love.” I guess the baby was the sun, and perhaps parents were the flowers, as though the baby grows the parents. It wasn’t particularly profound, but it was worth not being erased.

Anita told my mom to sit on the exam room bed, and I sat on a chair behind the door where, if opened too quickly, the doctor or anyone coming in would have been surprised to find me sitting there.

Next to the whiteboard were bios and photos of the OB/GYN doctors in this unit of the hospital. Degrees from Duke, UC Irvine, UC San Francisco. All excellent schools, I thought, even though I don’t always believe in following the hierarchy of ranked institutions. Daughter of immigrants. Bilingual. Dr. R., I thought, is the best person we never thought we needed.

◆

I had a hard time getting up today. This whole week, I’ve gotten up at either 5:30 a.m. to make 6:00 a.m. workouts, or at 7:00 a.m. to give myself a little more time to sleep in if I had trouble going to sleep the night before. I’ve been very gentle with myself, which is, much like listening and talking to my body, a new phenomenon and practice that serves me.

I woke up today––initially at 7:30 a.m, along with my partner, who had to get to work by 9:00 a.m.––and let myself sleep in baby naps until 9:30 a.m., which became, 9:35 a.m., and then 9:40 a.m. I remembered that I didn’t need to be at mom’s until about 10:30 a.m. The comforter lulled me into a portal of cotton on cotton, and above me the super-light cotton sateen sat like a cloud, while below me I caressed the bed sheet like skin on skin. I needed every moment of relaxation, and so I finally got up at 9:45 a.m., released from feeling like the comforter was hugging me tightly and differently, for a last time of sorts, before it let me go. I got up from being rolled into the blanket, like it was a set of long, flat arms. The blanket released around me like a small wave, crashing back down into the bed. I want to say that the comforter offered me a warmth I hadn’t had, though what’s truer is that I experienced a warmth I gave myself.

◆

Dr. R. came in the room moving swiftly. I imagined that she was in between appointments, but needed to make the time in this appointment meaningful, with a conversation spacious enough to inhabit all of our thoughts and feelings. Her white coat, paint-splatter colored pants, and grey Crocs made me feel comfortable knowing she was, too. She shook my hand, introduced herself, and greeted Ma, picking up from where they left off previously.

She pulled up her doctor’s chair close to Ma and they sat knee-to-knee. We all held our breath.

“Unfortunately, Mrs. S, we got the results this morning, and you do have cancer. I know we talked about this as a possibility when I last saw you, and we determined that it’s uterine cancer.”

I had thought about this moment for myself, or for other friends who’ve learned about their diagnoses, or their family members’ diagnoses, and I have seen many scenes from movies where folks were doing exactly what we were doing: sitting in a doctor’s office receiving the most untimely news of our lives.

◆

I was late to picking up Ma because I stopped by Jamba Juice to get her a Mango-a-go-go, and to get myself an Açaí Primo Bowl. If I had known that it actually takes seven to ten minutes to make a bowl like that––believe me, I timed it––I probably would not have been ordering it at the exact time in which I should have arrived to Ma’s house to pick her up.

I realized then, as I was filling out a Jamba Juice customer satisfaction survey, that I was soft-pedaling around getting to Ma’s house, which meant getting to the hospital sooner, which meant getting closer to a diagnosis, or to an answer, or a problem, to a possible date that I didn’t want to happen.

◆

I never thought I’d experience a cancer diagnosis in person. Now, my mind often slips back into Dr. R’s patient office, where Ma took a deep sigh, as if to say, “I knew it. I fucking knew it.” And I cried, wiping streaming tears onto my lip with my pointer finger, letting it all drip down my cheek, or sliding down into my palms. Ma looked down, and sat her arms and hands to her side, the way people do when they are sitting at the edge of a cliff, to hold on for dear life. I warmed Ma’s cold fingers with my left hand. I stroked the tops of her fingers with mine, feeling the natural wrinkles and folds of her knuckles to beneath her nails. Skin on skin.

Dr. R said what she needed to say––an asterisk break in glass, a pocket knife incision that exited as it had entered. “Mrs. S, do you have any questions for me?”

◆

My anger is old, and awakening from unannounced dormancy––a sleeping sun dragging, beating itself back to the sky.

I am angry with myself. It’s April, and I’ve known that my mom has been using menstruation pads, post-menopause, since last October. My mom has always collected, organized, and consistently made order from much ruin. I like to think I can be the same way in my work or writing life. Sometimes, I believe that I can take a break from those habits, and that break becomes my personal life––never enough time, but enough to keep me not exhausted. I thought my mom used the pads for daily vaginal discharge, the way most women use panty liners. I thought it was normal. What’s normal is my mom taking a free menstruation pad from the bathroom at her work place–just in case–every day for six months. Sometimes, she’d give me a pad if I was at her house and needed one; a lesson learned when I sorely needed it and she didn’t have one available, and I childishly got upset, even though I knew my mother had already gone through menopause years prior.

Does cancer create a new normal? What’s normal to my Filipino family in America is our hoarding of everything free and everything Costco has to offer in bulk at a discounted price. What’s normal is needing everything, “just in case,” when your supplies run out, or come scarcely when you grow up poor in the Philippines, or working-class in America, or when you are always an immigrant like you are always a child of immigrants. It is more likely in our lifetimes that things will run out and leave us empty-handed. This is why my mom stocked up on menstrual pads. Like she stocks up on Spam. And pennies. Like I stock up on frying oil. And books. So that we can never say we don’t have enough. So that we can have a relationship where what’s normal guarantees our survival. So that anger and sadness don’t come from hunger. We stock up so that we can relax a little bit. It’s not privilege, it’s more like preparation. But not even our shared hoarding could have helped me sharpen up to see that for six months my mom used four pads a day––where four in one day is a heavy day in a monthly cycle. I am angry with myself because I did not take her to the doctor sooner. Because I didn’t ask her what she did with the pads. I presumed, as I did with most things, that it would be stored and unused for a little while longer. This normal never should have been.

◆

“Is it curable?” my mom asked.

“Yes,” Dr. R. affirmed. She then explained that my mom is in good hands with her, and any doctor at the hospital. Ma was brave, asked about next steps, and Dr. R. recommended meeting with a surgeon who would likely perform a hysterectomy. She set us up with more appointments with another doctor and more tests. She sent us to meet with a surgery scheduler, and directions to a trip to the hospital’s patient coordinator.

◆

The night before the doctor’s appointment, I took an epsom salt bath with lavender, lemon, and peppermint oils for hella long. This is part of an ongoing self-love routine that has taken me most of my adult life to be okay with incorporating. I must have been there for at least an hour, pruning. Something in me kept me there, in that water of myself, to sit and stay and listen to my body for longer than usual. As if my body knew that I needed to brace myself for an emotional wave.

◆

“Hey, it’s going to be okay,” Nurse Anita shared. “I want you to know that I have cancer, too.” She pointed to her chest. “Breast cancer. It’s been three years now, and I’m still fighting and working.” Oh shit. I had no idea. My mom and I were in disbelief, and our one-word responses were the fullest parts of speech we could cobble together.

“I work here, and I am happy because the hospital really is doing their best.” Oh, I think we said, unsure if this was an inopportune advertisement for the hospital. I thought that we needed all of these signs, all of these strange affirmations. We needed assurance that our time was precious, yet unflinching. That if cancer is a day that never ends, it would be because we wouldn’t let ourselves succumb to its force. If cancer is a day that never ends, then we would end the day, choosing shut-eye to continue life anew in the time we have left. Cancer, I hope and need, cannot take my days with my mother from me. Cancer, I feel and even know, can take my mother from me and leave me with a motherlessness I have always feared. I don’t know a world, much less a future, without her in it. Nurse Anita was a tall, husky woman, probably standing at just under six feet tall. Her imitation-quilt plaid scrubs looked at a glance to me like thick stripes, and the shape of her breasts made them look larger than they already were. How could cancer be in there? I thought to myself.

“I come from Mexico. You come from your country, right,” she directed to my mom. Mom nodded gently, intent on hearing what Nurse Anita had to say next. “This is just my opinion, but I think we get cancer because of all of the shit we eat in our foods, all of our processed foods––it’s not like our homelands. Not like our food. We eat a lot of shit with chemicals, and it’s toxic, and I think it affects our bodies.” I could not agree more. I think Mom silently agreed, too, as she usually does. Anita reached out her arms out for a hug, and hugged back. Their hug ended in a handshake and turned into a short hand hold. What other comfort could we offer each other at that moment?

◆

After the appointment, Ma and I went shopping at HomeGoods and TJ Maxx. How fucked up we were. How we bought all of the discounted Adidas-brand Warriors gear we could find in the men’s and women’s clothing sections, even though my mom had just started getting into them because her co-workers were. How I bought discounted candles, again. How we sought to build parts of home with each other. How happy it made us. How Ma, somehow, still had space in her heart, mind, and wallet for her sister and brother-in-law, my auntie Regina and Uncle Lloyd, who were moving to the Philippines in a week. How she almost bought Uncle Lloyd a Warriors t-shirt for $9.99, and how we both rejoiced when we found a better one for $7.99, like we had won something worthy of fighting. This victory, not ever too tiny to be remembered. This moment, not ever too forgettable in any time post-diagnosis. This mother of a day, where we didn’t afterwards talk about doctors, or feelings, or anything that we knew before it was announced.

◆

I didn’t tell my mom that I have been thinking about the Philippines. As I was driving on I-280, the same freeway that takes us to the hospital, or to shopping plazas, a voice inside me said that I needed to plan a trip, and that it might be my last trip home to the Philippines with my mom. That I have a lot to learn and remember, that I am open enough now to actually follow through with this plan––this language of unspoken love that I have for my mother is one of naming and action. Mostly, this body of text is calling on me to plan (our last moments) and prepare (the body).

◆

I’ll never forget the Winter Break when I learned that my friend Lisa’s mom had bought enough house slippers for her family of five––Lisa and her two siblings, herself, and her husband/Lisa’s dad––and had a basket full of house slippers at the front door of their house for the four of us friends meeting the fam for the first time in their own, well-decorated, Christmas-themed house. Lisa’s mom was young, into exercise dance classes, and was very talkative; these were all qualities I wished for myself and my mom at the time.

April 6th, 2018 was the same day that I had planned to drive to the Chapel of Chimes in Hayward, CA for Lisa’s mother’s memorial services and eulogies. Lisa is a homegirl from a past life that involved much Hennessy, short dresses, high heels, and clubbing in San Diego, Oakland, or San Francisco, and Mexican food from Roberto’s, El Farolito, or Taquería Sinaloa. My friend Crystal and I were going to meet up and attend together, to pay our last respects to the woman who welcomed us into her home like any other accommodating Filipina mom. I had to cancel these plans, as I told Crystal that I had to take my mom to her emergency doctor’s appointment. I wanted to be there for Lisa, who had for the ten years I’d known her, a mother who was fighting cancer, and had recently lost her to the same struggle I’d just inherited.

Lisa’s mother fought, won, and lost the battle against cancer three times: in 2008 when I first met Lisa, in 2011 when we lost touch, and in 2018 when I saw her for the first time with her motherlessness meeting mine.

Later that weekend at her mother’s memorial, I did not tell Lisa about my mom’s diagnosis. I didn’t want to make the day about me, just as I didn’t want to prolong the emotional toll on her. The last thing I wanted for either of us was to reach, deep down into the wells of our memories and multiple realities, for the little and lot we do for ourselves in the horizon of our mothers’ efforts to survive.

◆

I joined a ballet barre gym about a month before Ma’s diagnosis. When my new yoga instructor asked us to close our eyes, bow our heads to set an intention before we begin our practice that first day in the new gym, I listened to my body for the first time in ages. I looked at myself in the mirror, hands at heart center, ready to start a new life with myself, closed my eyes, and heard my body unlock a wave of relief in my chest, stretching from the top of my lungs to underneath my collarbones, “I want to stop hating myself.” It’s in this particular mindful yoga class that I think often about how I wish Ma was there instead of me. How I wish I could work out for the both of us.

In my body is a language I’m not listening to closely enough. The yogic intentions started to deepen, and I’m opened to opening up: trust yourself, energize yourself, push yourself to see how strong you are, breathe through difficult situations. How I wish I could sweat out enough of the pain and Ma’s cancer for it to go into immediate remission, even though I know that’s not at all how it works––but what is logic to an unplanned illness? Cancer came inconsiderate. How does science, or writing for that matter, assuage the sadness that takes front, middle, and back seats in my head, chest, stomach, work schedule, my arms, and legs? What stories or sadnesses might Ma have blanketed in her body, in her uterus? And how am I connected to these sores or growing cells? What does it mean, really, to die slowly from inside ourselves? My body, I think, tells me dying is not dissimilar to living.