Not Jenny. Not Michelle. Not Katie. Not Cindy. These were the names of the girls in my grade-school class, oftentimes in triplicate so they had to be called Jenny L., Jennifer H., Jen T., and so on. Jenny was the most popular name of all. A name that shines like a penny you make a wish with.

When I tell my friends about how I got my name, they think it’s hilarious. It says a lot about my mother. My mother, very pregnant with me (I envision my fetus-self not as a watermelon, but as a hot air balloon filled with fire and a basket of perishable snacks), was working the cash register at the restaurant when it dawned on her that she has to give her daughter an English name.

To fit in. She says this phrase, in Cantonese, at least three times. To fit in. To fit in. To fit in. As if casting a spell upon America – the incantation traveling from shore to shore. And so, when the cash register slams shut like an alligator’s jaw and the door jingles open, she asks the stranger who walks through.

“Can you name my daughter?”

The customer is truly from Jersey and does not even skip a beat. “Yeah, sure. How about Maria?” The customer is Mexican American and is picking up an order of chicken and broccoli with some spare ribs too. We are known for our spare ribs – lacquered in hoisin gold. I used a spare rib as a pacifier growing up. My teeth strengthened, deliciously. My mother folds over the brown bag twice and staples it shut, the receipt dangling like a tongue.

She struggles. Her tongue doesn’t know where to reach. She hasn’t gone to night school for English yet and won’t go for a few more years. She gets as far as “Ma,” which is actually what she’s about to become. Despite living in the States for less than a year, my mother is already a Jersey girl. She also does not skip a beat. If there’s something that has never changed about my mother, it’s that she never wavers. “No, sorry. Try again.”

The customer cradles the food in the crook of her arm and says my name while walking away. The food can’t get cold. My name travels with her like a drowsy bee, almost out the door.

“Jane,” my mother repeats after her.

The phone rings and my mother picks it up. But before she takes another order, she covers the phone with her hand and shouts loudly so that the Customer-Who-Named-Me can hear her over the car’s engine: “THANK YOU, SEE YOU NEXT TIME!” They both smile and wave at each other like queens sharing a float.

The best part? My mother does this again with my brother, Steven.

◆

Even though my name is common, it wasn’t ordinary then or now. I have trouble finding my name on magnets at gas station rest stops. Which is actually fine, because why would you want a magnet with your name on it anyway?

When I was born in 1984, Jane was not a cool name. Jane lacked some serious ‘80s flare; my name didn’t have shoulder pads or any sort of radioactive fluorescence. Growing up, I never knew another Jane. It would take me until graduate school, in 2008, to meet another Jane. In fact, I met two Janes at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, both poets I admire. Underneath one of my Facebook photos, one Jane commented “Hi Jane” and then the other Jane commented “Hi Jane,” and all three of us “liked” everything. This is how rare we are these days.

My name is short and blunt like the bowl haircut I had for years as a child. The “a” is sharp and nasally–– meant to be sung by someone with a deviated septum. Meant for someone with the peak of a white person’s nose, not flat and small like mine (it will take me over thirty years to love my nose). Sometimes, my name sounds like a rusty tool you use to fix a broken sink with – inadequate for such daily annoyances. Sometimes, it bellows forth like a goat sticking its head out of a barn after a sudden downpour: “Jaaaaaaaaane.”

My name startles me, especially when I’m not expecting it – when someone calls out for a Jane at the grocery store or the gynecologist’s waiting room. Whenever I hear a stranger call my name, my spine always stands a bit straighter, as if I’m being hit with a ruler. My name is not allowed to hunch over, not allowed to overflow like a pool of foamy sludge along the shore, not allowed to shove handfuls of chips into its salt-speckled mouth.

Stand up straight, my name demands. Or else you’ll stay like that.

◆

My first name and last name are common in two very different continents, empires. My name: a reluctant, rickety bridge or a deep crevasse no one can forge. Let’s start with my last name, which is how Chinese people do it. For, I’m also trying to prove to you that I am a little bit Chinese and not a total failure–– not a gweilo, a white ghost.

Wong, one of the most popular Chinese surnames, could mean “king” or “yellow” depending on what kind of family you are from. Considering I come from a poor farming family, a “peasant” family, it’s definitely the latter (how I’ve always hated that term, how the word is often confused with “pleasant” as if poor people are so nice, so happily stupid). But let’s say yellow like gold. Like gleaming, buttery 24 carat gold. I want to be gold leaf yellow, the kind of edible gold a chef uses tweezers to put on a lobster roll. An egg yolk drooling Wong, Meyer lemon Wong, canary singing Wong.

In the hellscape of middle school, I heard all the insufferable jokes. Wrong Wong. Jane Slong. Jane Bong. Wonky Wong. What’s Wong? In all this inanity, which continues into adulthood believe it or not, I have to remind myself there are some great Wongs. There’s Anna May Wong in the Roaring ‘20s, the stunning Chinese American Hollywood starlet. She was in The Toll of the Sea, one of the first Technicolor movies. The colors were as sharp as the stereotypes that cut through her, in all shades of sickly seaweed. Anna May said it herself: “I was so tired of the parts I had to play.”In 1935, the director of The Good Earth–– a film about Chinese farmers adapted from a novel written by a white woman— refused to consider her for the leading role and instead cast the white actress Luise Rainer.

I shake my head with my Wong sister, in solidarity. What someone so talented can withstand. It makes me furious with love. I pull our last name closer to me, a tether in a Technicolor I rewrite. In the future, Anna May gets to be whatever kind of Wong she wants–– in real life and in the movies. She gets to douse all that racist Hollywood mess with golden gasoline and light it on fire. Imagine, the glow of that warmth held to your face.

And what of my first? Jane, used in the 16th century for English daughters of aristocrats as an alternative to Joan (a name that sounds sweet and melancholy, holds a kind of ennui Jane can’t have). There are two queens from this time period: Lady Jane Grey and Jane Seymour. Lady Jane Grey, also known as “Jane of England,” was only a queen for nine days. She was eventually executed because she posed a threat to Queen Mary. In a painting of her, Jane looks like a ghost puppet in overflowing burgundy robes. Her arms are spread apart in an impossible hug, like a bear trap that can’t close. She looks terribly severe and unhappy. Looking at her, I feel my whole body react–– involuntarily shaking itself loose, limb by limb. And of course there’s Calamity Jane, infamous for wearing men’s clothes and drinking herself mad. She’s idolized. The American West loves a badass. An ox team driver, a sex worker, a cook, a nurse, a waitress. What often gets left out: a supporter of the murder of indigenous peoples. Some people might use the term “frontierswoman,” but this is what this term means.

None of these Janes look like me and I am pretty sure that, even though we share a first name, they would take one look at me and shove me firmly under their boots. I want nothing to do with these Western Janes.

◆

If I’m going to be honest, I keep forgetting how to say my Chinese name. There’s no guarantee at allthat I’m even writing or saying my name correctly at this very moment. I have to call my mother every few years and ask her to say it out loud. My mother only speaks to me in English these days. My Chinese name opens like an old, fermented jar of garlic. Can you say it again? I ask, over and over, until I’m dizzy with the pungency of my name. I say my name out loud, lifting it to the air like my favorite amusement park ride, the swing carousel. My name: flung out to the furthest corners, the guttural tones blurring together. Was I saying it right? I wobble in my shame, like I’m about to shit my pants. Can you say it again?

The only time I hear my name naturally is when I’m around my grandparents. When my Gung Gung was alive, he would announce my name like it was the time of day. Hang Neoi. He affectionately added “girl” (“neoi”) to half of my name. I loved how resolutely he said my name, as if it opened doors. My Yeh Yeh and Ng Ng nicknamed me Bao Bao, my cheeks as large as pork buns. Bao Bao, they’d say, holding my face up to theirs, my big eyes shining on them like a seaside lighthouse. When my Yeh Yeh fell seriously ill, my brother and I visited him at the hospice. On the ground floor, the receptionist asked us: who are you here to see? My brother and I looked at each other, completely flustered. On the verge of toppling over. Yeh Yeh, we said in unison. How could we tell her we don’t know our grandfather’s actual name? How could we explain that our grandparents earned this title, the grandest of all titles, and let go of their actual names? The three of us looked at each other, not sure of what to do. Let me just go through some Chinese sounding names, how about that? she finally said, trying her best to help. My brother and I went, floor by cold floor, trying to find him. Amidst the vases of plastic daisies and halls of empty gurneys, we saw our uncle who led us to our Yeh Yeh. When we saw his actual name–– for the first time–– on the whiteboard outside his door, we stared at it with wonder.

I have one surviving grandparent, my Pau Pau, who lives in the Central District in Seattle. Each day, she leaves fresh oranges and flowers by my Gung Gung’s framed portrait. My Pau Pau always laughs, tipping her head back like a pitcher of water, when she says my name. Once, when my aunt and I visited her, we let ourselves into the apartment. She always leaves her door unlocked. My grandmother was cutting the ends off string beans when we entered, the little green tails gathering in a pink plastic colander. She looked up and laughed in soft surprise, Hang Neoi, the scissors scrapping her fingers. Pau Pau, I greeted her, weighing her warm hands–– a tiny spot of her blood along my palm. I held on tightly until it stopped bleeding.

To write this essay, I ask my mom again. I call and ask her to remind me what my name means. “It’s like something naturally fragrant. Something you like. Like lavender or chamomile. But not actually,” she tells me. “Your Yeh Yeh named you. He knew I missed home. Your name sounds like missing home, but it’s not.”

Not actually? But it’s not? Confused, I ask her to write it down for me in Chinese. She pauses for a bit. “Oh my god,” she says. “I forgot how to write it.” I can hear her in the post office break room, waving down a Chinese co-worker of hers. “Jane, I’ll text it to you later.” After all this talk about my name, she tells me that her co-workers are having a party during break today. On the other side of the country, I imagine my mother with a party hair and her lunch whirling inside the microwave behind her. She tells me there’s a wheel you can spin to win a prize. “Let’s see if I’m lucky today!”

The text comes through later at night. My Chinese name is written on a napkin. One of the characters looks like it has dimples. When a Chinese American friend of mine looks up the characters (I’m completely illiterate in Chinese), she finds the words “vegetable” and “fragrant.” Homesick with top notes of various vegetables and a hint of chamomile, eau de parfum.

Shu Hang.

At any given time, it’s bound to happen. I try to extra-enunciate. And yet. And still.

In the bewildering cosmos of my name, I have to let go of precision, clarity, correctness. I say my Chinese name like speaking into wet sand, muffled in sloppy grit.

◆

“It’s nice to meet you, Jade!”

The places you’ll find Jade: dinner parties, conference networking groups, dressing room chalkboards. Sometimes, I correct them. Sometimes, I just let it go. It’s not worth listening to their embarrassment, their arms-waving-over-their-heart apologies. One time, when I corrected a white woman, she said, “Oh my god, I’m sorry. How do you spell that?” As if there’s an exotic way to spell Jane. And my favorite of all, correcting another: “It’s actually Jane. Not Jade. My name is Jane.” And she had the nerve to respond: “Are you sure?”

Am I sure of my own name?

I was born in Long Branch, New Jersey. My mother loves telling me about how I looked like a doll, with my big eyes, bowl haircut, and perfectly frilly dress. “When we’d go to Chinatown, strangers would take pictures of you. They’d ask me if they could take a picture with the China Doll.”

“That’s creepy,” I tell her.

“Yea,” she says, shaking her head. “Sometimes, I thought they were going to kidnap you. And make you model for GAP Kids.” My mother wanted me to be a GAP Kids model so badly, she’d risk me getting kidnapped by white couples.

Despite being a native English speaker and reading early for my age, I ended up in ESL for two years. This was back in the day when you were pulled out of your regular classroom and walked to the “trailers” like you were about to be quarantined. The trailers were outside and linked together via a shoddy boardwalk. The nurse’s office was there too, full of nosebleeds and taffy-colored vomit. It was like wearing a “kick me” sign on your back for years.

I hated everyone in school and didn’t say a single word out loud until the fourth grade. And thus, because of this silence and the fact that I looked foreign, the teachers and administrators assumed I didn’t know English. So what if she’s clearly writing a novella in her notebook? So what if she’s read all the books in the classroom three times already? She looks like a chink, so…

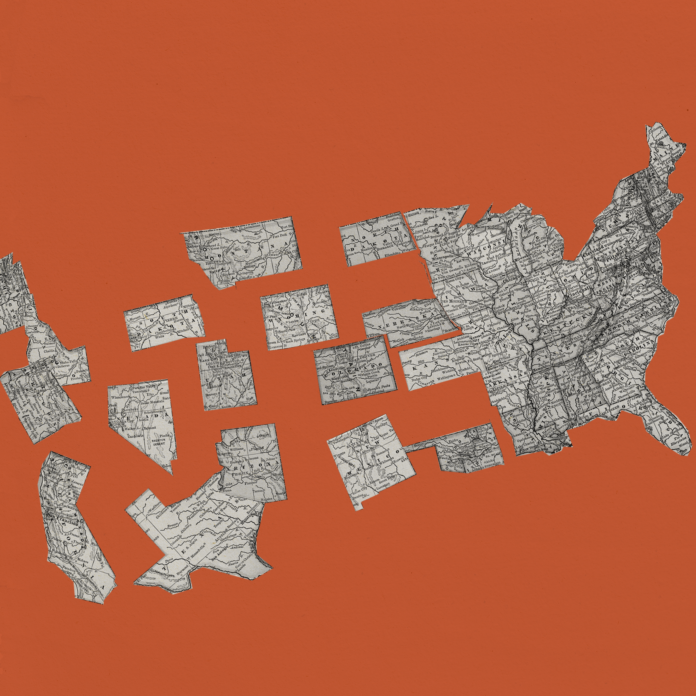

And there I was, in the trailer, refusing to do yet another puzzle map of the U.S. The ESL teacher pointed to the trailer door with its rusty hinges and slapped a sign on it that read “DOOR.” She smiled at me like a demented clown. “DOOOOOOOOOOR, Jane. Say it with me. That’s a DOOOOOOOR.” I sat there, my eyes burning a flame so bright it could light a million torches held by rats in mutiny.

They forced me to be the little Chinese girl, dressed in pigtails and a red silk jacket, to taunt a dragon on Culture Night. They forced my mother to bring in wontons from the restaurant on International Food Day. And those wontons, made painstakingly by all the women in our family, were delicious. When a shitty white bully, who looked me straight in the eye with glittering cruelty (Ching-chong, ding-dong, he taunted me during recess, touching my nose as if ringing a doorbell), doubled over and said the wontons were poisoned, they did nothing when all the kids started to fake-cry. You can imagine what followed: dog meat, MSG, dirty this and dirty that. Remember: my mother never wavers. The wontons are fine! she shouted with her arms raised, shooing them away like flies. Who taught you to be like this?

They were the reason I refused to speak for so long. These days, I can’t shut up. But, at the molten core of my voice, I always wonder: am I a traitor for writing in the language of the colonizer?

◆

I could call myself a dove, a winter melon. I could fall in love with my name in full, unabashed sunlight. Poet and activist June Jordan writes in “Poem about My Rights”: “My name is my own my own my own.” Repeating it makes it echo and ring in perpetuity. I think about how protective I am of my own name, how I hold it close to my body like a band-aid. To be seen, to be visible, to be human.

◆

How my ex-boyfriends were named: after Rick Springfield’s “Jessie’s Girl,” after a great-great-grandfather no one remembers, after the Bible before his parents decided to become hippies, after a guy his mother had a crush on in high school (not his father), after months of deliberation and divination via a book of baby names his parents paid real money for, to use just once. They always tell me their middle names–– which they prefer and wish was their actual name. But, I want to say: what is the difference between a Chris and a John? What good is a name you never use?

“What’s your middle name?”they ask me.

“It’s just Jane Wong.”

“That’s it? You really don’t have a middle name?”

I’ve always wondered why they thought this was weird. What were they thinking? How simple, how pedestrian, how plain? Jane Wong? Just two syllables? Just two skips of a rock in a pond? You only need rain and a pothole to skip a name that short. Two syllables like two taps of the gavel in Law and Order.

It’s funny how someone can make you feel like you need a middle name. I actually considered getting one, as if one could “get one” like picking up a puppy from the shelter. I could be one of those cool Asian Americans who had an identity awakening in college and use my Chinese name. Jane Shu Hang Wong. Or, because we are often mistaken for each other, I could use my mother’s name. Jane Jin Wong. As I filed this in the back of my head of things to think about, I opened up Facebook and saw my little brother changed his name: Steven Jay Wong.

I texted my brother immediately: Steven Jay Wong?!

He texted back: So what? It sounds cooler.

I didn’t know this was a thing. My brother completely made up “Jay.” Was it after the bird? Or was it to be closer to us, sealing our family triumvirate through our first initials: Jin, Jane, Jay? My brother is earnest enough to do something like that and I love him with the fierceness of a wolf pack for it.

Here I was, a grown woman trying to come up with something I never desired in the first place. Honestly, I don’t want any embellishment. I don’t want this extra flare of personality. Not the supplemental, downy softness my ex-boyfriends desired of me: no Rose, no Sophia, no Lara, no Isabelle in the middle. I don’t care how plain Plain Jane sounds, how old fashioned, how no-frills. I don’t care that there are a million Jane Wongs in the world. For once, I want to put away my glitter, my bright red lips, my patent leather boots. I want to hold my name up like a simple blade of grass and ask my baby cousin: what color is this? Not emerald, not chartreuse, not forest. Green, he’ll say. My name, just like that.

◆

Throughout middle school, I had an alter ego named Wayne. Liz, my best friend, was the tallest girl in our class at six foot and growing. She collected terrifying Victorian dolls with collars like frilled lizards and loved sipping steak blood, which her family poured into tiny Dixie cups clearly made for tequila shots. Liz loved Wayne the most. And when I was over at her house, Wayne would cause all kinds of trouble.

Some things about my alter ego: she’s a cheesemonger and lives in a cheese cave. She plays R&B tunes on the clarinet, is known for her renditions of Boyz II Men. When boys throw rocks at her (which happens to Jane, coincidentally), she kicks them right in the balls. Wayne is a thief, a total flirt, and wears her boyfriends’ t-shirts as mini dresses. She has dark blue hair, the color of a Steller Jay’s mohawk.

Once, at Liz’s house, Wayne made a concoction from all the booze from her parents’ liquor closet, the Curaçao swirling together with the rest of the clear and honey liquids like a galaxy. Moving from cabinet to cabinet like a jewel thief, Wayne fortified the elixir with hot sauce, Welch’s grape juice, horseradish, red liquid from cocktail cherries, and clam juice. Liz and Wayne poured the mixture (both wearing kitchen gloves because who would want to touch that) into an empty Coke bottle and spent the whole night convincing Liz’s little brothers to drink it. One of her brothers took a sip and curled up in a ball and cried like a broken sink. Liz and Wayne poured the entirety of the concoction into a bowl of cereal just to see what it would do. Wayne wanted to hear the sound. The sizzling incineration of each Cheerio, glugging its way down to the bottom of the bowl. She took a picture of it with a disposable camera and told Liz she’s going to send this to her boyfriend in lieu of a love poem.

For the record, all middle schoolers are weird people who tip toe around the edges of indelicacy. And it’s obvious that my alter ego was more akin to building an altar for who I wanted to be–– or who I truly was, at least partly. I needed Wayne, my familiar stranger. I needed her to refuse what people expected of me. Jane: polite, quiet, shy, deferential, forgiving. Media teaches us these roles, returning to lovelorn, docile Lotus Flower in Toll of the Sea.

Later in life, men will expect me to be their “babe,” their “baby.” They will play me Velvet Underground’s “Sweet Jane” in the morning, as if this has never been done before. They will kiss me hard and whisper, “You’re bad, you know that?” as if I was supposed to be good. I will get messages on dating apps like “will you be the Jane to my Tarzan?” and “you remind me of an anime character I used to love.” Later, I will fall in love with a man who showed up at one of my poetry readings, a man who said my name like scaling a waterfall. He will love me in all my contradictions and never call me “babe” or “baby,” just Jane. And I will let my guard down and tumble into each cherry blossomed tree, each muddy mass of moss. And he will leave to Denali and call me a few days later and say: “I’ve never loved you. You are not real. You’re a fantasy. Did you expect me to move to some random town for some quirky girl named Jane?” He will use third person. I will become some other entity, some ghost self. Insert for a name: any girl. I will fall silent again. I will walk through the world like a leaf. I will beg to have my name returned to me. My mother will call, will carry me once again. I will hold my name fiercely until it grows new selves. I will listen to the sounds of garbage trucks outside and their prehistoric arms, crushing everything we throw away, and demand that every single person must see me–– fully and completely–– as I see myself.

◆

My mother likes to tell me about a blanket I named “Nose” as a toddler. The blanket was completely falling apart. I used to stuff my nose with the soft cotton, twisting it up so I could only breathe through my mouth. According to her, I spent a lot of time twisting up the cotton, like I was trying to get the perfect ratio of cotton to nose. It was important that the cotton was still connected to the blanket. “You couldn’t sleep without Nose. You’d cry: Nose! Nose! It was weird. I was worried there was something wrong with you.” In the telling, I love how my mother says this last part, as if this couldn’t possibly be her daughter, this weirdo, this future poet.

Nowadays, I sleep in fists. When I wake in the morning, my hands hurt from being curled up all night. I shake them loose in the morning fog. At night, I surround my bed with books, pillows, and plates of leftover pizza just to know something is there. Too many bad or disappearing men, too many things that terrify. How could anyone sleep normally?

When my mother visits me in Seattle, she always sleeps in my bed with me. Apparently, most people put their parents up in a hotel. I would never. My mother would be offended. She takes up the entire bed, her legs and arms outstretched. She makes little animal noises when she sleeps. I always sleep stick-straight, at the edge of the bed like I’m about to fall off a cliff. “Are you a mummy?” she jokes. She tells me that, when I was a little baby, she’d have to stick her index finger under my nose to make sure I was still breathing. “You never move. It’s so weird.” Once, sleeping with me in my Seattle apartment, my mother jolted up in bed and shouted “THE BONES!” I woke up immediately, laughing uncontrollably. Then she started laughing so hard, she kept smacking the wall. Then I kept going, my face aching like it ran a mile from laughing. It was like this for some time–– this rollicking train of laughter and tears and drool. Rolling around in bed, legs kicking in the air like synchronized swimmers, we chanted in our delirium: “THE BONES! THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES THE BONES!” (The market gave us free beef bones and she forgot to put them in the fridge.) When I sleep with my mother, I never sleep with fists.

My mother and I get our names mixed up all the time. My mother’s name is Jin Ai, which translates to something like “simple” and “love.” Her maiden name: Huang. We have matching moles – hers above her right eye and mine under my left clavicle. We look alike; it’s more than obvious that I’m her daughter. We have the same lips, the same smile, the same proclivity toward eating things that take patience to consume: we bite each corn kernel, crack open every peanut, dig our claws into each absurdly tiny crab leg. When I lived in Montana, I received her W2 in the mail. When I get mail at my childhood home in Jersey, she forges my signature, pretends to be Jane. Our names sound similar, ringing together like bells: Jin, Jane. Because America, some of her coworkers call her Jean instead. And some people spell her name Gin, which welcomes Dad jokes about mixed drinks.

“We are the same,” she tells me often. She speaks in analogies all the time, and maybe this is why I end up becoming a poet. “We have the same light inside of us. It is so crazy bright, some insects are drawn to it and some just go blind. Do you know what I mean?” I think I do? Can you repeat it again?

I love these stories of hers. The Insect Light, The Nose Blanket, The Customer Who Named You. There are so many, I can’t recount them all in my lifetime: the time she cut open a boy’s foot, the time she stole her purse back from her thief, the time we sang “Who Let the Dogs Out!” at full volume after my father left our family, the time her sister-in-law broke all her plates and dropped me on my head–– in all these stories, we look almost exactly the same. These stories become mine, passed down through so much blinding light.

My mother didn’t name me–– not my English name, not my Chinese name. She calls me by my true name: her daughter. Hers. Her reflection, her double. “That’s my daughter,” she says all the time, as if we are twin moons. She announces this to her coworkers who we run into on the street, to strangers by the cantaloupes at A&P, to me especially, when I am red-eyed and hunched in heartbreak. You’re my daughter. In other words: you will survive this, because I have. Jin’s Daughter with the Crazy Bright Light. I earned this title and I move into it, a waltz of kin I know so well. Insects buzz around it, testing their trust.