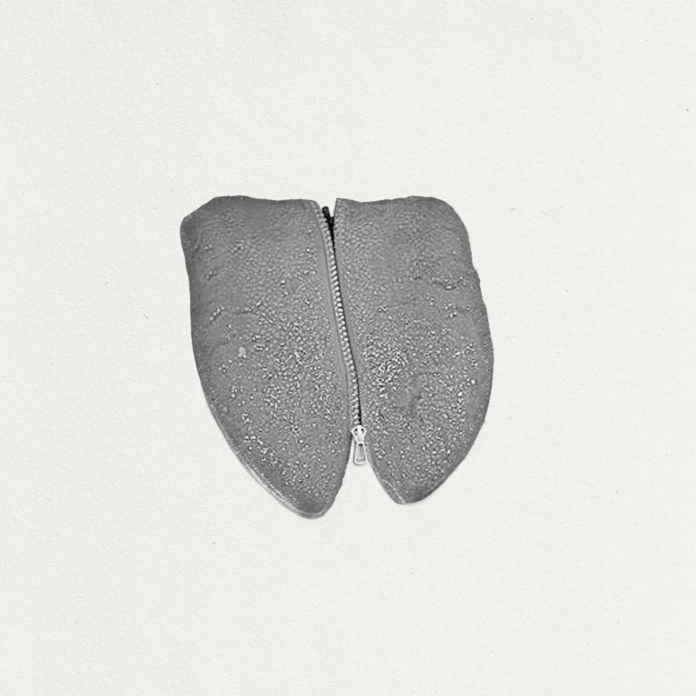

The night before her grandmother moves in, Holly soaks her tongue in vinegar. It floats in the clear liquid: pink, bumpy, unzipped at the frenulum. The fissures on her tongue are magnified by the glass it swims in, and when Holly holds the highball to her eye, she sees everything else bigger: the toilet bowl, the mottled brown tiles, the water-stained taps that are labeled backwards. Online, it said ten minutes in acid would make a tongue soft enough to re-mold. Holly starts a timer and lets the shower rain toward an empty tub: an excuse so Ben won’t wonder.

Ben knows that Holly’s tongue comes out, of course, but witnessing it makes him uncomfortable. She’s the first Removeable he’s ever dated—and besides, tending to one’s tongue in private is something Holly learned from her mother.

“That’s not nice,” she’d snapped years ago, when she saw Holly removing it during Saturday morning cartoons. It was the same tone she used when she caught Holly touching herself, and Holly zipped her tongue back in a hurry, catching the inside of her cheek. Later, when Holly’s mother gave a familiar cough during dinner, she told Holly to come with her to the bathroom, where she turned on the fan and faucets before removing the food that was caught in her zipper’s grooves. “You never let the sound carry,” she whispered before they walked back to the table where Holly’s father, a Standard, was waiting.

In the decades since, Holly has mostly removed her tongue for situations like her mother’s: things caught in the zipper, that regular itch no one talks about in public. She hasn’t removed her tongue to try to Flip it in years—but her grandmother is coming tomorrow, and her grandmother only speaks Elsewhereish. This morning, Holly tried forcing the Elsewherish side of her tongue in place, but something about her dad’s Standard genes have made her grooves too smooth. She found the vinegar tip after hours of scouring the Internet—soften the tongue to reshape the connective ridges—and while the website said there might be a burning sensation afterward, Holly doesn’t care as long as it works.

The steam from the shower lifts a rancid scent through the room; Holly sprays Lysol to cover the smell. She swills the glass and imagines her tongue softening papilla by papilla, each bump on the surface readying itself to move the way it was supposed to move, in the twists necessary to greet Grandmama in fluent Elsewhereish tomorrow. Even partial Elsewhereish is better than what Holly can currently do: motion to her grandmother to follow her upstairs, boil water in case she wants tea. Holly just wants to be able to say hello tomorrow. She just wants to say how happy she is to have Grandmama staying with her while Aunt Lin’s family is on their round-the-world trip.

The timer flashes when it’s done; chime silenced for Ben. Holly puts three fingers into the glass and moves them like a vending machine claw. She opens her mouth and presses the Elsewhereish side to her zipper, waits for it to catch in the grooves. She shifts, presses harder, but it still won’t latch. Somehow, her tongue seems tougher than before.

Later, when Holly gets into bed, she faces away from Ben. She can smell the vinegar on herself: on her tongue, her lips, her fingertips. Ben fits his hips behind hers, hums his words against her neck. “It’s our last night alone for a while,” he says, and Holly feels herself pulse in response. Six months of sharing a bedroom wall with Grandmama are ahead of them—tonight they should take advantage, scream themselves hoarse. But if Holly opens her mouth to scream or moan or simply breathe, she knows the scent of vinegar will overwhelm Ben, and she can’t bear to see the way he’ll recoil. “I’m too tired,” she says, straight into her pillow, trapping the scent in the down.

◆

Holly rises before dawn to soak her tongue again. This time she tries lemon juice, fresh-squeezed so the teeth-scrapes along the sides are still stinging when she hears her intercom buzz.

She expects to find Grandmama in the lobby with Aunt Lin, a woman whose tongue is so skilled she can Flip it from English to Elsewhereish with her mouth closed. Instead, Grandmama is by herself, leaning against the wall. The jade precious to her region of Elsewhere adorns her wrist; Holly feels the cool stone brush against her skin when she takes Grandmama’s hand and leads her to the apartment.

Drops of lemon juice wring from Holly’s tongue as she dials the phone. On the refrigerator, there’s a carefully-written list of things she needs Aunt Lin to translate: Watch out for the mouse traps we keep behind the garbage can. Put your dirty clothes in this hamper and we’ll take it to the laundromat for you. If the toilet won’t stop running, get Ben so he can fix it. Don’t put your hands near the garbage disposal.

There are things on the list Holly is looking forward to sharing, too: Here’s your room, here’s how you turn the television on. Here are some Elsewhereish DVDs in your dialect that I special-ordered online. If you want to listen to music, press this button and you’ll hear a reed pipe recording like the one you played for me when I was a child. Beside your bed, there’s a plant I had imported just for you. She imagines the smile that will appear on Aunt Lin’s lips as she translates, the way she’ll Flip her tongue back to English just to commend Holly on being so prepared—but when the video call picks up, it isn’t Aunt Lin’s face on the screen.

“My mom’s driving, we’re on our way to the airport,” her cousin Susan says, expression smug as always. “What’s wrong? Did you lose her already?”

“I thought your mom was coming upstairs. I need some help explaining…”

The last time Holly asked Susan to help her say something to Grandmama, Susan pulled on her pigtail and taunted, “You have a tongue. Use it.” This time, Susan rolls her eyes as she Flips her own, and suddenly everything on Holly’s list embarrasses her. When she shows Grandmama to her room, Holly stands in front of the bamboo plant on the nightstand so Susan won’t see. The bedspread Holly took so long picking out—the same shade of red that Grandmama wears on special holidays—clashes with the apricot walls, and she can tell from the way Susan purses her lips that she thinks the room is too small.

“There’s not really anything else to go over,” Holly says, even though a full page of her notes is unspoken. An abrupt fullness in her throat keeps them in. Ben whispers to her about the garbage disposal and Aunt Lin chimes in from the driver’s seat, “Remind her not to cook when Holly isn’t home. She keeps forgetting things on the stove.”

The apartment is loud with all of them talking—louder still because the neighbors in 4C are renovating, and when they get close to Grandmama’s bed, they can hear the pounding of a hammer, the whirr of a circular saw. Grandmama puts her hands over her ears and says something in Elsewhereish, and Susan yells through the phone, “What the hell is that, Holly? Can’t you see it’s too noisy for her?”

But later, when the call has ended, Holly understands there’s something worse than noise. Noise is texture, experience, proof of life. There is no noise as she and Ben and Grandmama sit in the living room. Holly taps a finger on the coffee table to make sure her ears are still working, and Grandmama looks over like the tap holds meaning. It’s only the first hour of her six-month stay, and already Holly is out of things to do. She points to the TV, thinks maybe she’ll turn on an Elsewhereish DVD, but Grandmama shakes her head “no” and Ben says he’s going for a run.

“Are you hungry?” Holly asks Grandmama, pointing at her own stomach. She goes into the kitchen, picks up an empty saucepan, and holds it in the air. “Hungry?” she repeats.

Grandmama shakes her head again, so Holly stands alone in front of the stove. Her tongue feels tough and heavy behind her lips, and her throat aches in a way it hasn’t before. She paws through the pantry, emptying things into the pan as she goes: a box of sour candy, a peeled grapefruit, the bottle of cranberry juice she keeps in case of UTIs. She stirs in what’s left of the vinegar, makes a note to buy more tomorrow.

Her idea is to bring the mixture to a low boil, as hot as she can without cooking her tongue. But when the organ’s unzipped Holly can’t taste or feel it tingle, and she needs the sensation of acid in her mouth, needs to feel the burn. She ladles it into her mouth until her eyes water, then swallows, unzips her tongue, and ignites the stove.

◆

During the day, while Ben is at work, Holly sits and Googles. She’d planned to use her summer break from teaching to bond with Grandmama, but the acid soaks aren’t working fast enough: two weeks have gone by, and she and Grandmama still exist in a silent orbit. “I used metal to re-structure my grooves,” a comment deep into her Google search suggests, and Holly starts looking for hex keys and paper clips in her junk drawer.

In the evenings, she cooks her usual meals, but the way Grandmama picks through the baked chicken and potato dishes makes Holly feel guilty. She emails Aunt Lin for Elsewhereish recipes, but she doesn’t recognize a single ingredient on the list.

Ben also sulks through dinners. They eat fast so they can be done sooner, but the after-dinner routine is worse. Before Grandmama arrived, Holly and Ben would smoke a bit before bed, mess around on their phones, show each other stupid videos. They’d have some kind of sex before sleeping, at least with their mouths, at least with their hands. Now, they simply sit in the living room with Grandmama until she’s ready for bed. Holly flips through the channels for those shows that don’t need words, the kind that involve people tripping over themselves or flinging their bodies over padded walls. Everything is too quiet, even when the crowds on TV cackle and scream—but once Grandmama goes to sleep, the quiet becomes something Holly must preserve. She pleads with Ben to wear headphones when he turns on the Xbox, moves his hand away when she feels it searching beneath their sheets.

“I can’t live like this much longer,” he says one night during dinner. “We need to get back to our normal routine.” He glances at Grandmama, who pushes rosemary chicken to the side of her plate with her chopsticks. Holly thinks of the poached birds Grandmama buys in Little Elsewhere—the kind she places on her home altar while incense burns beside it—and she wishes she’d purchased one of those instead. “It’ll even be better for her.”

Holly stabs a potato with her fork and chews til it’s liquid. She feels rage at Ben for presuming to know what’s best for her grandmother, then rage at herself for knowing her guess is as good as his. That night, she thinks normal and doesn’t turn away when Ben rolls toward her, though she uses her hands and legs to still him whenever the bed springs creak.

Ben is snoring not long afterward, and Holly slips out of bed and tiptoes past Grandmama’s door. She takes one of Grandmama’s metal chopsticks from the kitchen and unzips her tongue, pressing the chopstick against it until faint impressions stamp her flesh. She holds her body weight against the metal, deepening the marks, pushing down on it with all her strength.

◆

Holly repeats the process every night until she learns about the GrooveGuard, a product designed for the type of restructuring Holly’s trying to accomplish with hex keys and chopsticks. She finds out about it on a defunct message board, and while the archive doesn’t let her post, she’s relieved to find a group of people like her. She’s encountered hundreds of other Removables but she’s never met one whose tongue doesn’t work; for a long time, she thought she was the only defective Removable in the world. Even Susan, whose biological father is a Standard like Holly’s, doesn’t have this issue. Holly doesn’t know if it’s genetics—just the scramble of a Punnett square that made Susan’s grooves textured and the ones on her own tongue too smooth—or if it has to do with something more: that Holly’s mother stopped Flipping her own tongue as soon as she immigrated Here while Aunt Lin Flips hers daily, that Susan attended a special school in Little Elsewhere every Sunday for years.

On the message board, Holly learns where to buy a mold for the GrooveGuard, how to boil the plastic and fit it to her glossoepiglottic fold. She learns that if you’re having trouble, you should check for tonsil stones—ones that are thicker, harder, than the kind Standards get. It suddenly makes sense: that lifelong intermittent throat ache, that unbearable fullness since Grandmama moved in. In the pockets of a Removeable’s tonsils, she reads, shame collects.

Holly orders a GrooveGuard, even though it costs more than she makes in a month. While she waits for it to ship, she shines a flashlight in her throat and presses on the swollen flesh. Stones the color of chicken fat pop out, one by one like a string of stinking pearls. The taste of the stones is one Holly recognizes from the back of her throat—an acridness that rises whenever she has to explain her broken tongue—and the volume is endless. She expels twenty-five years of embarrassments and failures, knowing she’ll only accumulate more. Even when they’re out of her body, they linger: lined up on the ceramic sink, more real and obvious than ever before. Holly crushes a stone between her fingers and shame spreads onto her skin, making her hands reek so badly a bottle of dish soap doesn’t help. She puts on gloves before Ben gets home. “I messed them up when I was cleaning. Flared up my eczema.” Ben looks at Holly like he knows there’s something she’s not telling him. Something calcifies in her throat.

◆

When the GrooveGuard arrives, Holly sets it on her nightstand without explanation. It comes with a tube of softening solution; she applies a few drops to the Elsewhereish side before fitting her tongue on the stand. Its metal prongs rise and fall in a replica of her grooves, and after pushing her tongue down into them, she takes a breath and rolls over.

“What…is that?” Ben asks. On his face, there’s a mix of confusion and disgust. Holly expected to feel embarrassed by his reaction, but instead she feels rage. It’s just a part of my body, she wants to say, though she can’t speak without her tongue. This is what it’s like to be with a Removeable.

Holly points to her mouth to show she can’t answer. She pretends not to hear Ben when he asks if she could maybe move “that thing” into a drawer.

“Again?” he says the next night. “What is it even for?”

Holly types on her phone and passes it to Ben: To fix my tongue so I can talk to Grandmama.

“What?” he says, but when she starts typing again, he rolls his eyes. “Can’t you just put it back in and talk to me? It’s like you’re not answering on purpose.”

I don’t want to waste the softening solution, she types, but she doesn’t pass the phone to Ben. He wouldn’t know what to do with that response.

In the morning, after her tongue is re-inserted, Ben wants to talk. “It’s been over a month and everything’s going fine. What do you need to change?” He argues with Holly when she says she can’t communicate with her grandmother. Wasn’t she able to tell Grandmama how to use the railings they suctioned to the shower? Wasn’t Grandmama able to explain that she needed extra space in the cupboards for her wok?

“And there’s apps you can use, you know, if you have to tell her something important—not to mention asking your aunt or cousin.”

What Ben can’t understand is that everything is important. She tries to explain what it was like when they lost Grandpapa, when a well-meaning teacher patted Holly on the back and said, “Tell me about him.” Holly didn’t have a thing to tell—she didn’t know if Grandpapa was kind or hardworking or smart. She didn’t even know his favorite food, his favorite color. She spent months afterward trying to force-Flip her tongue, because every time she looked at Grandmama she heard the Tell me about her that would someday come. But Holly was a teenager then, and her rushed, imprecise attempts led to chronic throat infections. After she suffered four infections in a single month, her doctor ordered her to leave her tongue the way it was.

“I don’t know, my grandfather was an asshole,” Ben says. “I would have been better off not knowing that about him.”

Earlier, Holly heard Grandmama laughing on the phone with Susan, and she realized she doesn’t know what Grandmama finds funny, or whether Grandmama is a funny person. She wants to tell her grandmother that she’s funny—or at least Ben usually thinks she is, that she fell in love with his laugh first, the way his whole body shakes whenever she jokes. And she wants to tell her grandmother that her favorite color is red because it reminds her of the pantsuit Grandmama wears to banquets in Little Elsewhere, and that if she has a daughter someday, she’s going to give her Grandmama’s name: Hong.

But Ben will never understand. She knows that from the way he hears the stress in her voice and doesn’t hug her, doesn’t acknowledge how hard this is.

“I think you’re making things too complicated,” he says instead.

◆

“Good morning,” Holly says to Grandmama the next day, and Grandmama nods in return. Ben’s right—there is some understanding—but that afternoon, when Grandmama wakes from a nap, Holly says “Happy teacup” as an experiment, and Grandmama nods in greeting as usual.

Holly’s in the middle of preparing dinner when Susan’s texts come, as insistent and plentiful as the pops of oil in the pan: wtf r u doing, seriously, she says her stomach’s hurting from the crap you’re feeding her, she has nothing good to eat. buy her all of these things ASAP, Susan writes, followed by a string of Elsewhereish. don’t u know what today is? r u even paying attention?

The pockets in Holly’s throat ache as she puts the half-cooked chicken in the refrigerator and gets on the subway to Little Elsewhere. She gets off at the wrong end—the most crowded section, filled with Standard tourists buying croissants and gelato—and wanders the streets. She pushes through until the crowds thin, passing a store that sells bright yellow patties filled with meat, a display of wine made from honey and gesho, a cart studded with chili-flecked mangoes on sticks. She hears music plucked from wood and steel, so many dialects of Elsewhereish that she can’t pick out a single thread. Signs in store windows spell Elsewhereish words in different characters and shapes and alphabets. All around Holly, people purse their lips upon finding their region of Little Elsewhere, drop their shoulders in relief after their tongues are Flipped. Holly bites down on hers until she tastes blood.

She reaches a store she recognizes from when she was younger; the aisles are tight and crowded, filled with vegetables. On the floor, there’s a box brimming with fuzzy melons that Grandmama used to grow in Aunt Lin’s backyard. She wants to touch the melons now, feel their tiny hairs on her skin, but she’s here for a reason. She takes out her phone instead and scrolls through Susan’s list. When she bumps into an old woman she apologizes, uselessly, in English.

No one here uses the English sides of their tongues. Holly senses that many are like Grandmama: elders who only ever Flipped to qualify for immigration, who found that English hurt too much to speak and never Flipped again after their green card interviews. Holly’s inability to speak Elsewhereish disrespects them, and by the time she’s back on the subway with an armful of red plastic bags, her tonsils are so full that she can taste the shame. It’s all she thinks about as her stop approaches: shoving the stones free.

But when Holly reaches the sidewalk, there’s another deluge of alerts from her phone. She sees Ben’s name in green stripes all over the screen: missed calls, voicemails, text messages. She plays one voicemail and hears the word “fire” in Ben’s panicked voice. She starts to run, bags of gourds and lotus root banging against her shins. Later, when she locks herself in the bathroom to gargle away her shame, she’ll find a spray of bruises, a red scratch across her knee. Now, she just runs harder, barely registering the bursting capillaries, the twist of plastic handles tight against her palms. When she opens the door to her apartment, she smells smoke.

Grandmama and Ben are in the kitchen, looking furious. Holly senses from the way they won’t look at each other that they’ve both yelled. Grandmama rushes toward Holly, her words rapid, her voice shrill. She points toward the metal tub on the floor of the kitchen, then grabs Holly’s wrists with her hands.

She doesn’t know the words Grandmama’s saying in Elsewhereish, but the metal tub gives all the context she needs. don’t u know what today is? Susan had texted earlier, and now Holly finally remembers: the anniversary of Grandpapa’s death. If she weren’t already breathless from running, guilt would take the air from her now.

“Okay,” Holly says to Grandmama, moving her head in big nods. After an afternoon confronting all she doesn’t know in Little Elsewhere, she wants to show that this, she understands.

Ben misses the exchange. He, too, points at the tub on the floor—does so with his fingers flailing, voice crazed.

“She lit a fire on the floor of the fucking kitchen. Where the fuck were you?”

“It’s fine,” Holly says, and she knows it is because that tub has been aflame indoors countless times before. When Holly was younger, she loved to watch Grandmama slip fake bills into the fire—afterlife money for their ancestors, Aunt Lin explained, encouraging Holly to pick up a stack of joss paper and throw it in. Sometimes Grandmama burned other things, too: scarves and gloves before wintertime, an empty packet of the cigarettes Grandpapa used to buy by the carton.

Holly tries to explain this to Ben: that this is fine, that Grandmama does this all the time. Ben brings his hands down on the counter so hard flour flies into the air. “It’s not fine, it’s a fucking fire. A fire, when you left grease all over the kitchen. You really think this is normal?”

Grandmama is still holding Holly’s wrists, looking small and frail. Holly can’t believe Ben would yell like this in front of her grandmother, can’t believe his choice of words: normal. Like the parts of Grandmama—the parts of her—that are tied to Elsewhere aren’t. It makes Holly think of elementary school, when the Standards used to point at her and pull their tongues. As she leads Grandmama to her bedroom, she remembers what those kids snickered before throwing her food to the floor: “You are removed from this lunch!”

When Holly returns to the kitchen, she screams. She says Ben doesn’t know what he’s talking about—he doesn’t respect her grandmother, doesn’t respect her culture. “This is sacred. This is how we honor our ancestors,” she explains. “And don’t you dare yell at her again,” she says, even though Ben swears he didn’t raise his voice. She repeats herself so loudly stones blow loose in her throat; she wants to throw up, but she just keeps yelling.

“I’m not being disrespectful, Holly. It’s just not safe. She set off the smoke alarm!”

Holly sees a penny-sized scorch mark on the floor, likely from paper that floated up from the fire and settled there as ash. She knows another piece could have landed in the oil that’s puddled near the burner, or on the sleeve of Grandmama’s flammable collared shirt. She knows fires indoors aren’t common Here the way they are in Grandmama’s region of Elsewhere, but she doesn’t concede these things. She wants to make Ben feel just a little bit as awful as she feels. He gets to go through life not knowing or caring about Elsewhere, and it isn’t fair.

“It is safe,” Holly yells, even as Ben walks away. “It is safe.”

Later, she cleans like it’s absolution: the counters, the stovetop, the floor. She shelves the groceries from Little Elsewhere, scoops soot from the metal tub, brings it to Grandmama’s room.

She tells Ben she’s sorry. “I know this is putting you through a lot—that I’m putting you through a lot.” He doesn’t look up, so she repeats herself: “I’m sorry. I’m sorry.” She keeps using her mouth to apologize, taking him so deep down her throat that her swollen tonsils ache. She smells herself on him when she lifts her head, and they fall asleep surrounded by the odor of her shame.

◆

The Elsewherish side of Holly’s tongue latches partway on the first day of August, and as soon as she feels the connection, she leans over the bathroom sink and cries. Somewhere deep inside the zipper, there’s the spark of nerves, the tingle of a current as neurotransmitters climb to her brain. Holly’s hands shake as she waits for static in her ears: the activation of another language sphere. When it happens, the change is slight—more like being splattered by rain than plunging underwater—but that doesn’t stop Holly from rushing to Grandmama’s room.

With her tongue only partway zipped, Holly can barely manage a whisper. Still, she tries, all susurrations and hisses, remembering something she read once, about a voice weak as a crippled animal, with jagged bones and splinters you could hear. Holly hears splinters in her own voice instead of words: just cracks, shards, and fault lines, all quieter than a yawn. Grandmama shakes her head at the silent ruptures.

Holly steps closer and closer, until her lips are nestled in the whorl of her grandmother’s ear. She imagines glue and stitches as she keeps working her tongue, imitating the Elsewhereish cadence, focusing on what she wants to say, and then—

There’s this laugh Grandmama has, this sound of half-surprise. Holly used to hear it when she was younger, when she washed the dishes all by herself or presented Grandmama with crayon portraits of her and Grandpapa. Tiny bumps rise on Holly’s arms when she hears that laugh now: proof she’s done something right with her tongue.

Holly can only vaguely sense what she’s saying, only gets the gist of Grandmama’s reply, but it’s more than they’ve ever had before. Hello, Holly says—thinks she says. Finally, she thinks she hears in return.

◆

Holly starts keeping her tongue on the GrooveGuard as often as possible so she can improve the connection from partway to full. In the days since she first spoke to Grandmama, she’s gained a few basic words—but she wants sentences, conversations. She wants the ability to express every thought that flows through her head.

“I’m glad you’re making progress, I really am,” Ben says when he finds her tongueless in the middle of the day. “But I have to say, Hol, I do miss talking to you.”

We can talk like this, Holly writes on a whiteboard.

“We can…”

And it’s not for long. Just until my grooves are 100%

“Okay,” Ben says. “I mean, I know this is important to you.”

It is, Holly writes. She looks into Ben’s blue eyes and remembers the way they glistened when he first said he loved her. It’s been almost four years of him holding her, supporting her, listening to her vent about her students, celebrating her small wins. She’s never had a partner that made her feel happier, safer, than him. But you’re important to me, too.

The dry erase marker smells sharp and chemical. Holly caps it and wonders if she’s asked too much of Ben since Grandmama moved in. She takes a biting inhale as she considers the ways she’s compromised their space, their patterns, herself.

“I know, Hol,” he says, lips brushing her temple. “I love you. I understand.”

But at night, something in Ben changes. “Baby,” he says, his voice soft and unsure, “it’s just—I don’t know how to kiss you like this. Can’t you just put it in for a bit?”

Or you can put it in… she writes before climbing on top of him. It’s good at first—sliding and frantic, and when he flips them over, she doesn’t even worry about Grandmama hearing the rock of the headboard. She tugs on his hair as she presses her face to his, but when his tongue slips past her lips and finds nothing, he goes soft.

“I can’t do this,” he mutters, rolling away. She’s still on her back with her legs lifted, close. “I’m sorry, Hol, I just—I can’t.”

◆

The ingredients Holly bought in Little Elsewhere stare down at her from the cupboards. She rinses the wok and cutting board before she confronts them, assessing them by smell and color. There’s a thick soup Grandmama loves that she wants to surprise her with, but Holly’s only option is to cook from memory because she doesn’t know the soup’s name or components. Her first attempt tastes too much like garden; her second attempt, too much like sea. She texts Aunt Lin and Susan for help but red exclamation points say her message cannot reach them. Finally, she manually Flips her tongue and knocks on Grandmama’s door.

The connection is stronger now but still incomplete. She wants to say Can you show me how to make that stew with shrimp and vegetables and those little white balls? but the only words her tongue turns to Elsewhereish are you and show and white. Holly leads Grandmama to the kitchen and points at the sliced greens on the cutting board, the shrimp, tailless and curled. How? she thinks she’s able to communicate. Help?

Grandmama’s face pinches; Holly sighs and leads her back to her room. She sweeps the food into the garbage, shoves her tongue on the GrooveGuard, and goes out for a run. On the sidewalk, Holly’s legs fly and her lungs pump with perfect control. She doubles her route, then doubles it again, relishing the way her body yields to her will.

Holly’s fourth time passing her street shows Grandmama in the apartment window. The fifth time, the blinds are drawn and Grandmama is a shadow between them. The sixth time, she’s nowhere to be seen.

Holly squints down the block at her building and notices a silver-haired woman hauling a laundry cart down the front steps.

No! she wants to yell, but her mouth is a cavern of teeth and spit. She crosses against the light, weaving through cars, but by the time she reaches the stoop Grandmama and her cart have already fallen. There is blood spreading where her head cracked against the concrete. Her eyes are closed and her body is terribly curled.

Holly dials her cell phone without thinking. The 911 operator asks about her emergency; Holly opens her mouth, but there is no sound. She wants to scream for help but her tongue is four floors above, suspended like a pig roasted on a spit. Can I text 911? Do they even answer texts? she wonders, panicking, until a neighbor shouts that he’s made the call.

Later, when Ben arrives at the hospital, he holds Holly’s GrooveGuard like it’s contaminated. Holly re-inserts her tongue with one hand, keeps the other on Grandmama’s shoulder.

“Don’t you think it’s time to give this up, Hol? Isn’t it causing more trouble than it’s worth?”

Holly thinks of what she texted him from the ambulance. I’m so stupid, why didn’t I have my tongue in? I couldn’t stop her and I couldn’t get help sooner and I can’t tell the EMTs anything about what happened. What if every second counts and it took too long because I couldn’t call? What if she dies and it’s all my fault?

They’re lucky: the wound on Grandmama’s head is held by butterfly stitches, and though her legs and arms are bruised, nothing is broken or torn.

“I don’t know. I’m getting close to reshaping it, I can feel it. I think, just a little bit longer—”

“But Hol, come on. You’re not even being safe anymore. I mean, look what happened. Will it really matter if you can Flip your tongue if your grandma gets hurt again?”

“This was a fluke thing. I thought Susan told her about the laundry, I don’t know why she tried to—”

“What if something happened to you when you were out running, Hol? What then?” Ben sighs, shakes his head. “It’s just, sometimes, lately, I feel like I don’t know you anymore. I used to always understand what you were thinking, and now…”

Holly listens to the machines beeping along with Grandmama’s heart and respiration. There are lines and numbers on the screen that she doesn’t understand, and in their green light, the bruises on Grandmama’s face glow. She leans over the bed rail to brush silver hair back, using one finger, thinking careful, careful. In response, Grandmama’s eyelids flutter.

◆

Holly lets Ben banish her GrooveGuard to the closet. She rids the apartment of acid, of metal, and leans into the almosts: If she places her hands in the center of her chest, she can almost tell Grandmama that she loves her. If she mimes her words when she recites a poem in English, she can almost get Grandmama to understand.

“I missed this,” Ben says as they whisper to each other before bed. When he leans over to kiss Holly, she can almost kiss him back without feeling a sting.

By the time Aunt Lin returns from her trip to bring Grandmama home, Holly and her grandmother even share an inside joke. Holly hugs her grandmother goodbye, then pulls back a few feet, raises her eyebrows, and frantically tugs at the front of her shirt. Grandmama laughs and copies her, harkening back to a morning at the start of the school year when Grandmama noticed Holly’s shirt was on backwards.

“What’s so funny?” Susan asks. Holly hands her one of Grandmama’s suitcases, smiling as she says she wouldn’t understand.

But a year later, when Aunt Lin calls in the middle of the night with news of a stroke that took Grandmama’s life, all the almosts Holly counted feel like dust. She comes home from the burial with dirt under her nails and tears through the closet without washing them first. On the top shelf, behind several boxes, she sees the glint of the GrooveGuard. She pulls it down and retrieves a stock pot from the kitchen: her own version of a metal tub.

When Holly clicks on her lighter, the flames catch in little licks. She doesn’t have joss paper so she gathers old newspapers and magazines to burn, hoping they will serve Grandmama in the same fashion. Before the papers turn to ash, Holly thinks of how Grandmama was prone to shivering, so she takes a blanket from the couch and cuts it up, dropping the cotton in piece by piece. She remembers how carefully Grandmama styled her hair, so she deposits a coiled pin, a bright pink comb. The plastic melts with a smell so noxious it’s almost visible. Holly breathes it in, thinking of what she failed to offer her grandmother in life as she slips a hex key, the GrooveGuard, and an empty tube of softening solution into the flames.

The apartment fills with smoke, but not enough—never enough. Holly writes a letter to Grandmama and gives it to the fire, hoping that when it reaches the afterlife, it will be transformed to something Grandmama can read. She remembers their shared joke and tugs at the front of her shirt before burning it, sobbing as smoke plumes toward the ceiling. She takes off her socks, her pants, her underwear. She pats herself from top to bottom, wondering what more she can give.

She thinks of Ben, then—Ben who dropped Holly off before setting out to pick up dinner, Ben who will come home soon to find Holly naked in the apartment, honoring her grandmother in a way he deems unsafe. Ben who was the only other person who couldn’t understand what was said at the funeral, who bowed and moved at the wrong times just like her. Ben who pressed warm washcloths to Holly’s eyes when her tears rendered them too swollen. Ben who is hiding a ring in his top drawer, in a satin-lined box that Holly finds unnaturally smooth.

There’s a crackle and the flames intensify, turning a deep red as they dance up to Holly’s chin. She reaches into her throat, thinking of the one word Ben will want her to say when he presents that box—the millions of words she wanted to say, still wants to say, to Grandmama. The blaze snaps as she unzips her tongue.

◆

Author Note: The story’s title and a handful of lines make reference to Maxine Hong Kingston’s “A Song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe.”