This is a rambling account of my recent travel, even if I am writing it in an email. I wouldn’t specify such a thing to anyone else, but I do it to you because I know how exacting you are about calling things by their proper names, just as you know how prone I am to losing my temper at the slightest provocation.

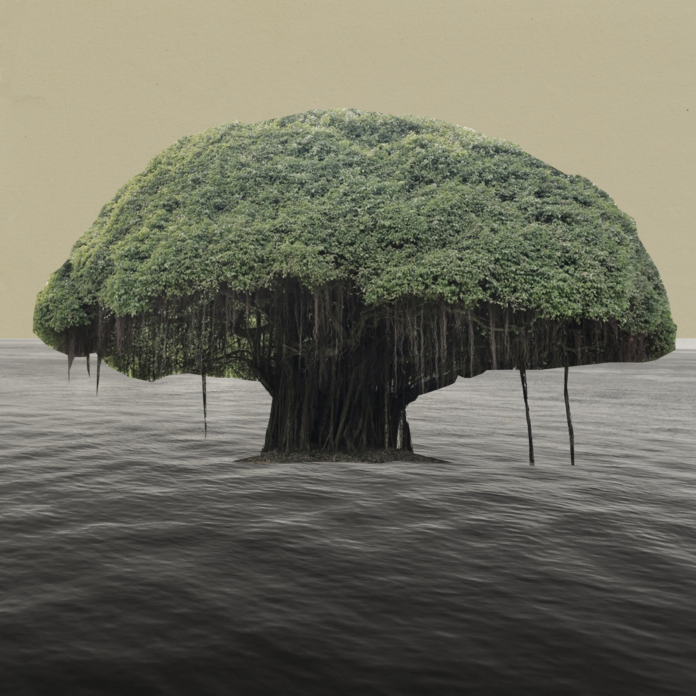

When my mother said she wanted to visit Kalboor to see the five-hundred-year-old temple there, I couldn’t refuse. The town and the temple had been underwater for the last thirty years and had resurfaced for the first time due to this year’s abysmal rainfall. I went with my mother to see this miracle — because isn’t everything that emerges from the water always a miracle? During the drive, I listened to her as she reiterated the story of how we had to abandon the place all those years ago. I am not sure what I remember from the time — I was only a three-year-old boy — but I have heard her recital so many times that her stories have taken the place of memories in my head. If she talks of the potters’ colony where she purchased the earthen pots for the kitchen, I can taste the coolness of the water that came from that ware. If she tells me the tremendous Banyan in the next lane was one hundred years old, and its aerial roots perforated the back-wall of our ancestral home, I feel the anticipation of coming across such an appendage in the darkened bedroom of my rented flat in Mumbai. If she tells me the door frame of that ancestral house was so low, my father had absent-mindedly bashed his head against it many times, I can hear his pained exclamation ring out in my ears. I resent my mother’s stories because they have infiltrated my memories, and I don’t know which life was lived by me and which was weathered by her. You will find this beautiful. You will call it love, I have no doubt.

Like us, all families from that town have the same surname, Kalboor, taken from the name of the place. Thirty years ago, when everyone was forced out because the dam’s height was about to be raised, and the town along with several other villages was unfortunate enough to lie in the dilated catchment area, they were rehabilitated to ‘Model Nagar’, an appalling settlement of governmental design. As we drove towards the state border and towards the two border-checks, my mother said she should have changed my surname to ‘Model Nagar’. She laughed, her face turned to the outside, towards the stone-breaking works which were going on everywhere, eating into the red laterite hills. By then, we had covered four hundred kilometers, having started early and made good time, and had left the black terrain of our western state behind. Perhaps my mother didn’t notice the change in the soil as she looked out the car’s open window and cracked her jokes. Maybe she was mocking the rehabilitation department’s naming strategies, or maybe she was ridiculing me. I can never tell with her.

Would you have accompanied us on this trip if things had been otherwise? I am sure you would have noticed the details my mother missed. You would have known how the air smelled like rain when we entered the reserved forest section of the Ghats. You might have exclaimed in delight when we passed a flowering cork tree. You might have unclasped your hair and let it fly in the wind alongside the wild scents. But then, you might have frowned underneath your smile at something I said that day or even many days earlier, something which you had held onto and carried forward in meticulous accounting. It is also possible that you might not have come with us at all, which, in balance, might have seemed better than if you had.

‘Why do all men wear the same kinds of clothes?’ my mother asked, out of the blue.

‘Which men are you talking about?’

Then for the next half hour, she pointed at boys and men chatting, standing by the village shops on the roadside; or sitting on gravel mounds, staring into their phones, or riding past us on speeding motorcycles, all wearing jeans and checkered shirts. I wanted to say that she was suffering from selective vision, opting to see only what would support her claim, but I did not say it out loud. As you know, I don’t feel close to my mother, at least not in the way I can be truthful with her. Then it struck me — maybe it was my father who wore checkered shirts. Now that we were heading back to the town where my parents had spent their early married years, could this be my mother’s way of mourning my father? I stole a glance at her face, but she seemed either tired or energized or perhaps both at the same time. I couldn’t sense the certainty of her grief. I turned my attention back to the road, where a line of loaded trucks had slowed down the highway traffic. I changed to the second gear and thought about the clothes my father had worn but couldn’t remember a single garment. The more I tried to remember, the more I thought about the tiny flat in outer Mumbai where we had set up home after leaving Kalboor and where my father’s heart had gradually weakened. I was old enough, ten, to recognize suffering when I saw it. Every evening, my father returned home from riding the local train and sat in the folding-chair kept by the door for a long ten minutes before he could speak or drink from the glass of water I had handed him. In Kalboor, my father had been an electrical engineer at the hydraulics power plant, some sixty kilometers away, and had travelled along a road lined with farmland and villages. In Mumbai, he became a maintenance engineer for the BEST transport company and had to cross the length of the city to get to work. One could say that not much changed for him. And yet, he seemed to become quieter as the days went by, and the noise of the city swelled around us.

It was my mother who had insisted we move to Mumbai, where she would have a chance to complete her B. Ed. and become a teacher. Perhaps she was already planning for the string of degrees, including the doctorate she would acquire later, that would ultimately make her the dean of an Arts and Commerce college. Earlier, when I said we had to abandon Kalboor, I meant we had to leave it under the force of my mother’s ambition. No sooner had the rumor about the proposed construction at the dam reached the town, my mother persuaded my father to leave. We never did settle after that, living in one temporary accommodation after another, and there was a time when I had to spend a painful year with my grandmother. If we had not left Kalboor, if we had not given up our share of the family inheritance, we could have chosen to live in a place better than Mumbai, in a place which had no need for local trains or the commotion that weakens the heart.

But I am rambling. I don’t think you are interested in my dead father or the inconveniences of my memory, so tell me instead, how is your new university and your new country? Is it everything you had imagined it to be? When you came to see me, I noticed you were restive, and I assumed it was because we were kissing for the last time, and the imminent separation was making our bodies unstable. I assumed this is what happens to people in love. But now that you are gone, I feel uncertain about that last intimacy. Were you, perhaps, looking for a way to hasten the parting while I, lagging behind as always, was trying to hold you a little while longer? Were you feeling a surge of relief while I had become numb with misery? When you reply to this email, you will have to be explicit and tell me what transpired between us that day. I need to know, and it is hopeless to assume I would understand without being told.

The interesting thing is, in her endless recollections, my mother never once mentioned the temple in Kalboor. When we finally reached the town, and I saw the temple’s old stone architecture newly covered in enamel paint, it struck me as strange. The temple meant nothing to me because it meant nothing to her.

As for the town itself, I thought the injustice of making people leave their homes, break their ties, and disrupt their communities ought to leave a shadow. I was not expecting a squall exactly, but perhaps something in the air, a gloom or an emptiness. Instead, I saw flex banners in profusion, directing people towards the temple, announcing which political party had made free water available for the devotees and which one had commissioned the paintwork on the temple. After all these years, people who had no relationship with the place wanted to profiteer from its misfortune. I parked the car a little away from the hysteria of the banners, and we stepped out. It was then, on the other side of the town where there were no throngs of people, I saw something unexpectedly beautiful. Parched land extended into the distance, cracked and cleaved into magnificent patterns, and further back, eroded structures stood in clusters partly on dry land and partly in water. It seemed as if someone had lifted the outer edges of Kalboor like it were a handkerchief, and the houses, schools and commercial buildings had slid inwards, leaving the edges sparse.

If I had expected my mother to react in some way, to feel moved by the terrain — for it was an oddly moving landscape — to draw her breath in at least, she did neither of those things. She was calm while I was wondering about the people who had lived in the water-eroded houses and walked on the obliterated streets. I thought, had these people been optimistic about their lives? Before they had been forcefully removed, had they put down roots and planned for the future? What had happened to them after they had moved? Then I remembered it was I who had lived here, along with my parents, my grandmother and my uncle in one wing, while my great uncles had occupied the remaining sections of the house. Who had owned the darkened back room where the Banyan had wormed its way into the house?

‘Nobody did,’ my mother said. ‘It was in the old part of the house. Nobody went there much, which is why they didn’t notice the damage for the longest time.’

‘But you did?’ I asked.

‘I was newly married and only seventeen. I was curious,’ she said.

Then instead of going towards the temple, she took a different direction altogether. I followed her as she crossed the empty stretch of land to arrive at the broken jawed houses, the post office that communicated with nowhere, the row of warehouses that stored splintered bricks and gravel from their own disintegrating walls, structures which were entirely exposed now that the water had receded to the center of the reservoir and left the fringes stripped. The sorrow that I had been looking for earlier was here, like a viscous fluid sticking to all surfaces. It felt like the shape of the town had been lost, and only the skeleton of despair had survived. We reached the place where dry land ended in a tract of mud, beyond which the water of the shrunken reservoir pooled. Some distance away, I saw a mound of laterite floating in the water. It reminded me of the red hillocks we had seen along the highway, and just like those landforms, this too looked like it had been mauled and left to die. This was what remained of our ancestral house. My mother was walking towards it, and for a moment, I panicked, as if she was going to do something drastic, or perhaps something was going to happen to her.

‘You are going too far!’

‘You worry too much.’ She continued on the muddy tracks, and it didn’t seem to bother her that the mud splatters were staining the borders of her cotton sari. Was she that attached to the house to let its ghost spritz mud on her chattels? You see, her behavior fascinated me. I have never felt that way about my memories or my possessions. Perhaps I have felt like that about you, but even that has become superfluous, as things stand.

Did I mention I wore my white linen shirt for the journey? I don’t know why. It is, as you know, my most expensive shirt. It crumples even while I am putting it on, which is why I avoid wearing it altogether. But I wore it that day. It was a plain shirt with no print, no color, no checks, just pure cloth if you like. I walked carefully as I followed my mother, and when I reached the place where she stood looking at the house, I ran a hand on my sleeve as if to make sure the wrinkles were where I expected them to be.

‘What are you thinking?’ I asked my mother.

‘There are not many ways to think about it, are there?’

The house looked peaceful, or perhaps it was the water, with tiny insects jumping in and out creating minuscule ripples, which radiated the sense of tranquility.

‘All done for future good, for the greater good,’ I said.

‘I have always been suspicious of grand words,’ she said.

‘Couldn’t we have stayed longer?’

She shook her head without moving her gaze away from the house. I wanted to ask for her reasons, but I believed she would have told me there was no point in staying when the governmental threat was looming over the place; she would have reminded me that no one wins against the institution, even if it might seem like that for a while. But when she spoke, she said neither of those things.

‘I would have liked to stay, but your father wanted to leave. We relinquished our share of the compensation and decided to hurry ourselves off to Mumbai. Your uncle and grandmother remained in Kalboor for a couple years until the time the government ordered a complete evacuation and moved everyone to Model Nagar,’ she said.

I felt exasperated. This was not how I remembered it. My father was the one who had pined for this place. I began thinking of the day we had left and about the two suitcases — paltry by today’s standards — which she and my father had carried out of the house. Only my uncle saw us off at the door, while my grandmother remained inside, furious, laying blame on my mother, saying it was because my mother wanted to become a big lawyer that she broke up the family, that my mother had always planned to do such a thing. I remember it was a clear day; the light was like glass, making everything a little shinier and a little unreal.

If I say that my mother’s answer that day shook my ideas about my father, and hence myself, you will say I have based my sense of self on mistaken foundations. I will disagree with you, and if you were here, we would have taken the argument deep into the night.

Do you remember that time when you and I went on a picnic riding my motorcycle? You said you wanted to go beyond the city, beyond the last village. I knew exactly where we could go. I selected the Ghat which was the closest and emptied of habitation far quicker than any other exit route. We kept going, soaked in rain, thinking of the unique romance of such a thing. But after every quiet patch of the road, we came upon another cluster of houses with a mobile phone shop thrown in for good measure. We never did go beyond the last village and had to stop at a small roadside eating joint that gave us simple food, and water in steel tumblers. You were not disappointed that we had failed in what you had set out to do. You said we must have taken a wrong turn somewhere and missed the bypass that would have taken us away from the bedlam. You looked terribly beautiful as you sat at the enamel-painted table, your hair subdued by the humidity, your long fingers holding the dented steel tumbler. It won’t surprise me if you are not disappointed with your new adventure and have no regrets about what you have left behind. But I still regret that I could not take you beyond, to the place where you had wanted to go.

Believe me, I did not want to go with my mother to Kalboor that day, even though I have always felt the magnetism of that place where I was born. I wanted to stay with you, finish our argument and see you off at the airport because it was clear to me all along that you would leave, that you had made up your mind. I wanted to hear everything you would accuse me of — yes, they were accusations, however much you try to deny it. Why else does one break a four-year-long relationship if there are no accusations and no perjury?

I remember one time you had explained our country’s inheritance laws to me because you were incensed by their history of unfairness. You talked about how these laws have evolved from not including women to grudgingly seeing them as equal successors to parental property. You introduced a new word to me: coparcener. What you said about things getting handed down to children interested me the most. While you were intent on the terminology, I was wondering if I have inherited my father’s weak heart, his lack of resolve, his displacement. After my father passed away, I lived with my grandmother for a while to give my mother the time to finish her doctorate. My grandmother was still bitter about how my mother had made my father leave home. One afternoon, as my grandmother dished out my lunch and I complained about the bottle gourd on my plate, she erupted, ‘God knows who you are anyway!’

That was when a suspicion took hold in my mind: who am I?

My uncle, who is younger than my father by four years but older than my mother by a year, also left home almost immediately after relocating to Model Nagar. He went to Abu Dhabi, got married, got divorced, and did not bear any children. What will happen to his property? Who will inherit it?

You always called me handsome because I am tall like my father, have a dark complexion like his, and a sharp chin which is more like my uncle’s than my father’s. What I have inherited has made me attractive. I have begun thinking about these things with seriousness. You are no longer with me, and I don’t understand how to look forward without looking back.

Earlier that day, when we were still driving towards Kalboor, we came upon a rough patch of the road. An excavator was plodding along, raising red dust. Canal work was in progress somewhere. When we came upon the site, I saw the partly-built watercourse yawning at an empty sky. It felt disheartening that even after thousands of years, we have not understood the nature of water; that we are still looking for and failing to find ways to stave off our thirst. But my mother was occupied with something else. She drew my attention to two dogs, one black and the other white, barking at the operator of the excavator. The man, comically thin like a skeleton, was manipulating the excavator while looking back and shouting profanities at the two dogs. I didn’t notice at first that the man was wearing a shirt of red and black checks.

I know that I have not addressed this email to you. It could be that I am afraid of the names I would want to give you. Perhaps, like you, I would be tempted to be specific with names, and you would have to become furious. I am not sure how you and I will measure up against such a role reversal. Perhaps I am not writing this email to you, but I am writing it to myself to understand why people are made to leave and why, sometimes, they choose to defect.

My mother and I stood looking at our house for a while, but we could not see it in its entirety. The ground floor was submerged, and only the upper floor, where one of my great uncles had lived, was visible like a water serpent raising its head above the surface. Afterwards, we traced our route back, but my mother took a detour into a narrow lane that kept twisting till I lost my sense of direction. This time, she did not tell me stories about the place, nor did she laugh at jokes she had made up herself. She was excited, and it seemed like she was seventeen and curious again. We stopped when we came upon a wall still standing upright, possibly because of its basalt stone masonry. Next to the wall, something grotesque had grown out of the earth. Before I could begin to wonder what the thing could be, my mother said,

‘It’s the Banyan tree I told you about.’

She said it simply as if the time had arrived to impart this piece of information to me as if to make a clean breast of it. I was confused. Wasn’t the Banyan next to our ancestral home, and hadn’t we walked at least a couple of kilometers away from it?

‘This house also belonged to our family. It was used as a storehouse after the larger residence was constructed, and everyone moved there many decades ago. Sometimes your uncle came here to study in peace,’ she said.

A sudden fury built up in my chest. I wanted to punch the hard basalt wall. I wanted to break my knuckles, if not my arm itself. My mother looked at me, and for a moment, I was gratified to see her become flustered.

‘Why did you talk about the two houses like they were one?’ I asked.

‘I never thought of them as two separate places, I suppose.’

‘But they are not the same place. This is made of basalt, and the other was made of laterite. They are separated by distance, by time. It was not my father whom you came here to see, was it?’

‘No. It wasn’t your father. Does it matter?’

The day had tipped into evening. The sky was unequivocal. I was stroking my knuckles, and my hand was hurting as if I had really punched it through a wall.

I must admit now, at one time, I thought of doing something horrible to you. You came home that evening, and while I was putting together a snack for you, knowing you would be starving, you announced your plans to resign from your job and move to the US for a Master’s degree. I was still cooking for you, and you were telling me how you had applied without letting me know, explaining why you had not told me before. But I didn’t hear your words. A pain flooded my head, and I had to shut my eyes before I could imagine doing something appalling to you. The only thing I remember is that what I wanted to do would amount to physical harm.

I know I will never send this email to you. I find it easier to plumb the depths of my feelings on this digital paper, something I would never be able to do in real life. Perhaps it appeals to me how easily the bits of this writing can be eliminated, how easily the evidence destroyed. I will not send this email to you; I will not ask how you are, whether you are well. The truth is, I would rather be misunderstood for the smaller crime of indifference than being truly understood.

At the second house, my mother held out her hand to me, a hand on which her veins appeared bloated and insistent. I didn’t move. I stared at the horizon where the light had softened.

‘You had a certain idea of our house in your mind, and you are upset that the idea is broken. I will not attempt to mend it for you because you must live your life with your own ideas, just like I have had to live mine. You see, life is not an isolated event. It keeps flowing, and sometimes it is prudent and even pleasurable to go along with it. In the end, even if you dam the river, water will have to flow, and it’s the same with life,’ she said.

She took my hand like she must have done when I was a child, and we began walking together. She did not need my support, but she held my hand like she knew what she was doing. This is the thing which has always maddened me about her — her self-assurance, and yours too. If you never needed me, why did you hold my hand at all? You will say you did it for love and not for dependence, and again I will have to be ashamed of myself.

When we crossed the partly constructed canal on the drive back, the excavator and its skeletal operator were gone. My mother was not looking out at anything, but when I looked at her hand resting on the open window, it was still marred with swollen veins. It struck me how strange her hand seemed because she is not that old, my mother, who married at seventeen. What made her hands age this way? And how had I not noticed it earlier? Night was falling, and it was only a matter of time before darkness would claim everything. I watched the road as it flowed like a dark river into the hazy distance, and it dislodged something in me. I thought about what you had told me about our country’s inheritance laws. I thought about how I had not paid heed to the things withheld from women, which was what had bothered you. When I had said, at the age of ten, I began recognizing suffering, I should have qualified that I saw only my father’s hardship and not my mother’s, who also travelled for hours to reach her college, and who, when she returned, did not have the time to sit in a folding-chair. I think I have suffered from selective vision. My mother did not choose to leave the doomed town, but my father did. My mother made other choices that I confess I cannot begin to understand. Is that why you left me? Did I fail to understand you as well? Or did you see through me and understood perfectly the kind of man I am?

I could have gone with my mother to Kalboor on any other day. She didn’t insist we travel on the same day when you were to leave. I could have accompanied you to the airport instead. I could have wished you the best of luck in your life, but I did not do it. I walked away. It is possible that I have been wrong about everything. Perhaps I needed to go see a temple in which I was uninterested, a town that had resurfaced, and a house that was submerged, to understand this about myself. What I want to say is that I too am a checkered man.