It sounded better than any class she had ever taken in college—or her entire life, for that matter—but Anna wasn’t sure she would be allowed in. The class had one of those sexy, creative titles that appeared somehow out-of-place in Stoddard College’s otherwise dry course catalog. It was called The Love Division: Breaking up the Literary Couple, and had to be a graduate class because it actually sounded fun. It had no description, only a short tagline and a booklist that appeared a tragedy unto itself. A syllabus that included Plath and Hughes, of course, and the Fitzgeralds, and Margaret Mitchell too, spoiling the end of Gone with the Wind for anybody who did not know. “Frankly, my dear…” But the subtitle was what intrigued her most. Anna had read it some twenty or thirty times now. It said: “Why does love die? This class seeks a consensus.”

A senior entering the final stretch, Anna registered for it anyway. She penciled the title on the add/drop form in thin, tentative marks in her dorm room and ferried it to the registrar’s office, where she submitted her last-ever semester of college. It was the end of the sleepy January term, the campus half-empty and snowbound, when students’ sleek desert boots made trails into ice, little grooves and striations like a red carpet, a history of shoe treads. So Anna slid to the bookstore for the reading list, hoping the professor might take pity on her after she’d spent a small fortune. Her arms filled with Kierkegaard, Rimbaud, Endless Love (getting home with two bags was like Mario Kart, mushing your feet through treacherous corners), she wondered about if Hamish didn’t let her in. She decided to write him a letter for good measure—his name rough but elegant, thick on the tongue, Professor Hamish Rawls—but what came out in her dorm room an hour later was as persuasive as a chain letter she wrote as a kid, made up of cut-up magazine words: Hi, I want to take your class. I am a senior. Please? Still, Anna delivered it to his campus box. She crunched from her dorm to the humid mailroom, her boots grinding up salt on the tile floor—a journey she made thrice that week, awaiting a reply from Hamish Rawls that never came. The professor didn’t know her from Adam. He could not possibly know that Anna’s own love had recently ended, and that she needed his class to put her back together.

Stoddard College was one of those elite Southern schools that lied about being “close” to things. Charlotte, Atlanta, Asheville. But it had its charms. A liberal arts paradise, it took promising minds and walled them in with cobblestones and evergreen trees. Tenured professors spoke of the world outside their gates like a hostile territory when really it was just central North Carolina, a region presided over by ugly Jesse Helms and a singsongy Dixie peaceability. If someone were hostile to you, you probably wouldn’t know it until it was too late. Especially in 1990, the height of Republican decorum in every nearby county except for Stoddard, the vague liberal exception. On the eve of a new decade, the campus had devolved. There were ’90s-themed parties, Prince 1999 parties, parties about future parties, parties where they greeted the future like a guest of honor. Indeed, her classmates predicted something great around the corner, but Anna didn’t see it. She had long overstayed her welcome at Stoddard anyhow. It had been too long. She’d first arrived on the scene at the overripe age of 19, then, when she was a junior, a yearlong leave of absence had become three years—years Anna had spent with her boyfriend at his house outside Atlanta—and suddenly she was 24 going on 25. Practically ancient. Nearly mid-twenties, she returned to Stoddard ignominiously, the madwoman of campus. A ghost haunting the merry corps of beer-battered undergrads.

The worst part? In order to still receive financial aid, Anna had to live in the dorms.

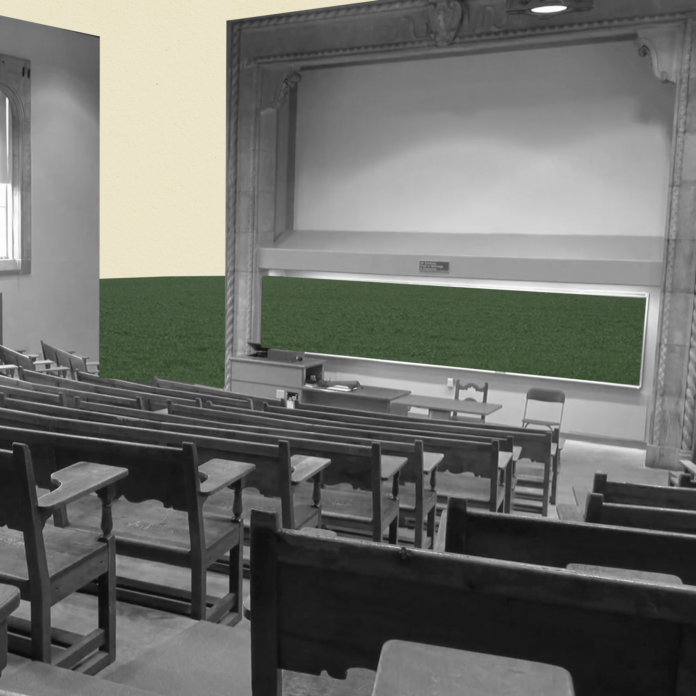

On the night of Professor Rawls’s first seminar, she blended in fine with the older graduate students. Incognito. The others dressed comfortably in sweats and flannels, so maturely dressed, with none of the ostentation of undergrads so primly branded, buttoned-up, and similar in style. Still, she fidgeted in her L.L. Bean jacket—an interloper ready to be cast from the ranks.

Then a booming voice from the front, too loud for seminar.

Hamish Rawls was young—perhaps mid-30s, easily mistaken for one of his students but with the bravado of a much older man. Suddenly the sexy course title began to make sense to her. So he was the cool guy. He wore chinos instead of pleated pants, chose topsiders over loafers—no belt, a t-shirt under his blazer. Anna couldn’t decipher the graphics on the shirt, but from the small windowpane above the buttons she guessed a rock group edgy enough for clout, some math rock dude outfit ready to burst free like Hulk Hogan’s chest.

“I suppose I know why you’re here,” he said. “Breakups! Yes, so terrible when they happen to you. But if suffered by someone else, they are quite entertaining.”

He had fabulous hair: a tsunami of thick auburn tresses, hearty and oiled as a salad, the kind of commercial hair a girl would kill for. Tonight it was swept into a bouffant, only a little dandruffed and he tousled it all the time—a nervous tic—which added to his insouciant appeal.

“This class will be different,” Hamish said. “Here, we will draw not only from literature and politics, but from, dare I say, the personal.”

Anna nodded. She’d predicted as much from the course description. Still, people gasped. This was new for them. Talking about oneself in class. He modeled it for them, going on and on, and she forgot she was nervous. At 6 pm, she grew hungry. The other students brought along rations of little Tupperware meals. They smiled through bites of microwaved pasta, stinking up the place. They ate while he spoke, to her confusion. Nobody said it was dinner theater.

“I want you to raise your hand if you’ve broken up with someone.”

Almost everyone raised their hands. It was not a terribly difficult thing to admit.

“Now, raise your hand if you’ve been broken up with!“

Hands raised slowly this time until they were united at last. She felt galvanized by this act: a cosigned treaty of weakness. Except she was lying. She’d never been dumped per se, but she could not afford to elicit any questions. Professor Rawls was insatiable. He’d certainly ask.

“Now, raise your hand if you were dumped by the person you loved more than anyone else in the world, and were ruined by it!”

Arms shot up even before he finished talking. She laughed. Who was this man? She noticed the bald patch: a double-crown cropped by age and worry like two bare planets colliding.

“Well then, let’s talk about it!” he yelled. “For us to get on, we need to know who! You! Are!”

Along with their names, they responded to the question, Why do you want to take this class? with answers layered and rich. By the time they reached Anna, she had absorbed their sagas of breakups, divorce, the cleaving apart of brilliant minds. Her stomach clenched—whether from hunger, sympathy, or nerves. She felt them all, their stories. Understood them. She may have been young, but she knew loss. When it came her turn, she choked on water. Said her name and her major but not her year. They didn’t ask. Perhaps they overlooked it or didn’t care.

“Well,” Anna began. “I suppose, like you all, I was in love too—a while ago.”

She hoped to leave it there, but Hamish wasn’t buying it. Everyone else spilled their guts.

“And what happened?” he asked.

“We met four years ago,” she said. “His name was Patrick. Things ended, now I’m here.”

Hamish waited a beat then gave up. Once he moved on, she unclenched. In silence, she repeated what she wouldn’t say: We met four years ago, then he died. Now I’m here.

Anna never thought she’d be the girl with the dead boyfriend.

It wasn’t like anybody remembered Patrick. They knew only the headline, that guy from years ago. Oh him? Yeah, dead guy!

Time on college campuses moved so fast that it was almost a kind of death, really: one day you were here, then after four years forever gone from this place. But she had risen, and like some apparition, had floated back to the epicenter of her lost love.

The grief struck her at odd moments, on the stairs of her dorm or in the cafeteria line. She didn’t fall over anymore, and had gotten pretty good at crying into a napkin, or the crook of her arm, or not crying at all, even–crying without tears. It took hold of her like religious ecstasy. A beautiful quote from her professor would send her there, beating on the heavy doors of some life she’d been cast out of, and she’d close her eyes and weep into the back of her skull. Gravity defeated tears. The professor likely thought she was napping—Anna couldn’t decide what was better.

It all happened so fast. She and Patrick had met as freshmen. The annual naked party. Her friends had been looking forward to it all week, but when young Anna finally saw them disrobe in the gross atrium, the coat closet with panties and brassieres nested into pockets, she lost her nerve. She would not take off her underwear. Refused to. Panties on, she felt about as self-conscious as a naked person would be in a clothed room. People stared at her while she stared at them. She searched between naked bodies for a fellow Adam or Eve, their privates also fig-leafed. Then her friends pointed out the costumed guy dressed as the school mascot, Snowy the Snow Leopard. Snowy traipsed from room to room, his outfit a mockery of animal coed nakedness. The theme was show up in what makes you feel sexy. Only when the humidity became unbearable did Snowy come up for air: he was cute, with the leopard’s sly smile, and he smiled at her.

They slept together that night. The underwear had been a wise decision, as he naturally wanted to see what was beneath. “You were brave,” Patrick said huskily, fishing down there. Anna tried not to get her hopes up. She was used to being disappointed by guys, but as Patrick tickled her in bed—running the length of her bare arm to see if it induced sleep as his Neuro professor promised—she wondered. She liked him because he was unconventional, funny, but still familiarly a douche. He was brave enough to ask for things. For instance, when he asked to keep sleeping with her, his curled hair still frowsy on her pillow, she had obliged, without demanding labels. Then, one Friday night, after they had been casual for three months, he did not show. Anna couldn’t sleep or eat, replaying all the times he’d ignored her in the dining hall, kicking herself for being such a modern girl. Why hadn’t they made things official? The next morning, she woke to her roommate Si Jun beating her awake with the phone.

“It’s him,” Si Jun said, humorless but dutiful. “Called three times.”

“Hello?”

Patrick had gone to visit family Atlanta in his treasured Winnebago, but a rare Southeastern cold snap had frozen the engine. Now the van would stay in the shop for two weeks.

“My dad drove me back,” he said. “Can I come over?”

“Sure,” she said. “Give me fifteen.”

Anna reached for her shower caddy.

“I tried calling last night,” he added. “Wasn’t sure if you were out.”

“I wasn’t,” she said. “No reason why. It was too cold.”

She heard Si Jun laugh faintly.

Patrick was a person who did things. When she was stressed over an essay, he brought her store-bought sushi that stank up the silent floor of the library; when she was bedridden over a bad grade or too much Smirnoff, he gave her a natural antidepressant in his brawny shoulders, carrying her on piggyback onto the campus green like Queen Shiba of the Dorm, one time bum-rushing her to the quad in her nightgown while she screamed; unlike her other boyfriends, he was unafraid of her camera. She photographed him often, cooking or cleaning or emptying the gutters at his parents’ house on weekends. Atlanta soon became a kind of sanctuary for them, a place to love without scrutiny from jealous friends or the intervention of his liberal parents, whom he warded off with a funny saying— “LOVE MEANS NO PARENTS ALLOWED.” It seemed they were alone even when they weren’t, every glance over a biscuit-recipe morning or wink over a Savannah fishing lesson, a sexier brand of foreplay than campus necking. They were falling in love. Anna was a bad driver but Patrick didn’t care, marshaling the stickshift with confidence until a rare bone cancer inverted the very order of things. Then he became the feeble one, and she took the wheel.

When he left the university for chemo, Anna departed with him. Two plus years later, she made the drive again in his old Winnebago his parents had generously gifted her, hoping she’d still visit. “Remember us,” they said. When Anna returned, almost three years later, all of her friends had graduated and every spot on campus had morphed into a new place to hold vigil.

For the second class, Hamish assigned two performance artists named Marina Abramovic and Ùlay, a couple who had broken up in 1988 in the most dramatic way, traversing exactly one half of the Great Wall of China each then meeting in the middle and parting ways to finish the rest. Anna arrived full of opinions. She was ready. The English department thrilled her in the evenings, so much livelier and more adult than the dorms. Outside the grad lounge, she heard the familiar chirp of gossip, the birdsong of campus life, and inclined her head to listen. The lounge was a VIP space that sanctioned department news, exclusive, Anna the only one not invited. She removed her new leather backpack and molded herself against the doorframe to hear.

It was the women from her class. Martha, et al. They were talking about Hamish’s divorce. She was a beautiful professor named Nina, and she’d left him! They suspected cheating, foul play. Anna sighed, figuring she might have known. She disappeared into class where Hamish, who said to call him “Hamish,” waited.

Anna sang like a bird that first session. Nobody seemed to know where she came from, making her speak freely and without self-consciousness, though not personally.

“I love it,” she said. It probably wasn’t the right thing to say, but she said it.

Hamish asked her what she loved about it. He lingered on her name—something about the honeyed way he said it suggested only a female could love such a thing. She said that Marina and Ulay were so intense and white-hot that anybody could have predicted an end to them. Then she noted the passion between the two artists, and Hamish smirked with the pleasure of someone neither disappointed nor proven wrong. Anna gestured at a glossy photo of them kissing violently, their mouths clasped like two mussels. Breathing in concert until one of them fainted, drunk on carbon dioxide. Passion!

“No artists had ever done it before. Used each other as art objects. It’s compelling.”

Hamish was unimpressed. Perhaps Anna had no idea what she was talking about. Maybe other people had done it. She had simply blurted this out because it was him: he made you want to keep talking, to hold his attention. The women in the grad lounge had admitted it too: they wanted to sleep with him. Including a girl with short hair who swore she would. Her name was Martha, and she spoke constantly, without subtlety, sometimes chewing gum in class.

“Why do you think we break up?” Martha asked Hamish, who only shrugged.

“I can’t possibly spoil it so early in the term.”

He acted like nobody in the room knew about his separation. Surely, he sensed their eagerness—their ravenous stare. They hung on his every word, but of his own heartbreak Hamish said next to nothing. Surely he knew grad students made it a point to know everything.

Then Martha sang the tale of her last relationship. He’d been a narcissist; she’d given him everything, had done nothing wrong. Then Hamish changed his demeanor entirely, open and transparent. He made use of these breakup bromides, even wrote them down for posterity with his blue Pilot G2. He took notes like a therapist, finding depth in trivial and inoffensive things.

It annoyed her. Anna wondered what he might write if she told the truth. If she admitted she was a performance artist. She had taken videos of Patrick during his last year—a hundred hours of footage on an expensive Sony camcorder they had bought with his Get Well Soon money. She was his caregiver, he said; she deserved it. The least she could do is make it art. Whenever she felt isolated, missing her senior year, Patrick would tell her matter-of-factly, “Yes, this will be a strange chapter in your life.” What would Hamish Rawls say to that? Probably not much at all, which is what scared her. The reaction she feared most was no reaction at all.

Still, it seemed they were the only two people in class unwilling to be honest.

The fourth week was about Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. It arrived with the fanfare of a jury trial. Students came prepared, their books peacocking with colorful post-its and dog-eared pages. Anna was disgusted by it. She regarded their fascination as bloodsport. People were so in love with the Sylvia Plath story, but as she’d read Ted Hughes’ poetry she could only picture Sylvia’s corpse sticking out of the oven, plain as day. Like how young children playing hide and seek often think it sufficient to disguise only their heads, their arms and legs twitching on the couch.

In class they spoke about death like they caught it on a microscope slide: a singular picture, freeze-framed: clinical, with none of the emotions that drove one to insanity, the aftertaste that made wives leap onto funeral pyres and sent mothers adopting feral cats or lifting up parked cars with small hands and broken acrylic nails. It was all too reasonable here, too clean, as if death was only personal, with none of the theatrics of breakups and silly relationships. And so Anna hid from everyone the images that haunted her, the flickers of death that overtook her, fried the electric grid of her spine, reminding her that Patrick had sucked in a few last breaths with wet lips and like Sylvia, was gone. Like a snuffed candle. She still held the sponge in her hand when he died, the one she’d used to give him water, his body basically doing only mechanical work to keep him suffering, the days she spent saying, “stop, let go, it’s okay.” Did her classmates know how long it took for a body to give up?

But before they could discuss Sylvia—her towels blocking the door to the kitchen, cloth keeping her children in the next room from murder-suicide—there was some housekeeping. The first item was the “assignment,” 50% of the final grade. The second was that rare thing: a party. An informal class meeting at Hamish’s home.

The class perked up at this. On a Saturday. With alcohol. They were ravenous for a party, of course, but the project got the most attention. Due in a month, the assignment was documentary-based. It was confessional. Hamish described it profoundly, speaking as if he were giving them a present, and Anna watched Martha grin ear-to-ear.

Anna felt inspired. She wanted to make a video about Patrick. She had the footage in a Coleman cooler stored in a locker in the dormitory basement where it had waited for months; here was an opportunity to transfigure it, even finish it. The next day, she set off to the campus media library with the cooler and Patrick’s old office key. He had worked in the film lab as a technician years ago, a time so iced-over Anna could barely remember it. But she had the key.

The space looked the same: shaggy orange chair, a scientific smell like dead air preserved in formaldehyde. She opened the cooler and observed the film, more precious than anything else she owned. Then she fed it into a monitor costlier than her first car, so absorbed that she failed to notice the lab technician had arrived for his shift.

“Wow,” said a voice. “Nobody ever uses that machine.”

Startled, Anna moved to shield the screen. Static tickled her hands. Electricity pulled her arm hairs, drawing them forth. Patrick was under there, making an impish, scrunched-up face. The voice belonged to a skinny boy. Wiry, feline, black-haired. She recognized him from the Hamish seminar, where he rarely spoke.

“I didn’t mean to scare you,” he said.

“It’s fine,” she said. “It’s just, I haven’t ever heard your voice.”

“I’m Tim,” he said.

“Hi, Tim.”

Something about Tim’s easy demeanor grounded her. Normally she’d want to know more, but the project beckoned. They had brokered a tenuous peace so long as he didn’t keep talking, which he did do.

“Most people don’t even know this place exists,” he said.

“Yeah, my boyfriend used to work here.”

My boyfriend used to.

Tim was curious. His eyes followed the monitor.

“Sorry, I’m just busy with this,” she said. “It’s for class.”

Tim waited a beat. “I like that class, I do. I just shut down in there.”

Anna winced, searching for final words. “I know what you mean.”

Tim wasn’t catching her tone.

“Are you going to the thing? The house party?”

“I think so.”

Really, she had not known she had a choice.

“I hope to see you there,” Tim said. Then he swiveled away. Harmless. That was that.

Later she realized this was the moment when she and Tim became friends. He even greeted her warmly in their fourth class. The topic was at last the Fitzgeralds, F. Scott and the ill-fated Zelda, which quickly transitioned into a fierce debate about who had abused whom. People started yelling. Tim raised his eyebrows at Anna as the drama crescendoed. She was grateful. It was a kind of friendship one relied on in captivity: comrades-in-insanity. Meanwhile, Hamish took neither side but egged both of them on at random.

He was crazy! She was crazy!

“What’d you think?” she asked Tim at the end of class. They left together, an easy harmony.

“I think they were both crazy,” he said. “You?”

“I think we’re all crazy.”

They walked to a 24-hour deli with a famous chicken parmesan.

“What do you think about Hamish?” he said, tentative.

Tonight had gotten out of hand. They both knew it.

“I don’t think he means any of it,” Anna said. “It feels like, I dunno, he’s having fun.”

What she wanted to say was, He’s running our class like it’s a breakup.

“He’s intense. It’s like, I don’t know, he wants to see inside you. ‘Tell me all your secrets!'”

Anna took a bite of her chicken sandwich.

“Have you seen his face when they cry?” Tim asked, because lately people had begun to cry.

Of course she had. She was surprised he hadn’t pulled out a vial and a stopper, collecting a draught for his home collection.

“I wish they wouldn’t,” she said.

“What, cry?”

Weren’t they embarrassed? She knew it had everything to do with Hamish, the avarice with which he guru-ed their lovelorn troubles, but she just couldn’t imagine it. Tim said he liked it when his classmates sobbed; bitterly, he said he enjoyed making fun of them. Then Anna disappeared into another bite. The sandwich was so oven-hot that she found it difficult to detect its true quality beneath temperature. But Tim seemed to have a different experience, his lips glossed in red sauce. She was supposed to be in the lab right now, pasting together her lost memories. This week she’d only gone when Tim wasn’t working, meaning she needed to go now.

“I think… I have to work.”

She pointed at her watch, then left Tim on the curb. He called out to her.

“Don’t forget about Hamish’s next weekend!”

Anna sunk into the project as one does an elaborate lie. She wasn’t sure how to present it to the class. What would she say? Would they feel betrayed? They barely knew her already. They were so convinced they had hacked into deeper intimacy. Poor Martha had even offered a flowchart presentation of her last three breakups, treating her classmates like her shareholders. Anna wondered at what point they would start dating each other: Martha with Tim, the rest banging around like molecules in a petri dish. Or perhaps she could even pretend like Patrick had not died. She could say she made a series of sappy videos because she wasn’t over him. But her classmates would hate the videos if he had lived. That was the difference. Without death, nobody would care about Patrick. Love? Nothing compared to sorrow. Anna understood this well enough. She too had often gagged about it until she had lost it.

On Saturday, she rushed from the laboratory to make herself over. Anna had no idea what to wear. She fetched a silver cocktail dress from behind a suitcase and tiptoed to the bathroom, regarding herself anew in the smear of the dented, oily mirror. Already there was music in the hall, where doors stayed open always. The hallway was a walk-in beer fridge—a party tonight. In the shower, a girl poked her wet head from behind the curtain.

“Katieeee!” the girl yelled. “Oh shit, you’re not Katie.”

“Sorry.” She caught her reflection in the fogged mirror, apologizing for not being Katie.

“Wow, that looks good on you,” the girl said. “You should wear it!”

“You think so?” she asked.

Yes. It still felt a tad formal, but who was Anna to deny her.

She shrugged. “Maybe I will.”

It was surprisingly temperate for March. Anna met Tim on the steps, swishing her dress against her legs a little. She curtsied as if to say, Hey, I know it’s too much. Then they knocked on the door, taking deep breaths.

“Greetings!” Hamish said. “I see you’ve arrived together.”

He nudged Tim, who blushed, looking to her for direction. Hamish handed them both a glass. Anna stared at her champagne a beat too long. It was the first time a professor had given her alcohol, the first time she’d seen his house, even. The place was cluttered, lived-in. It was a slovenly duplex of mostly books and tchotchkes, each broken-down gimcrack an elaborate story, each memento a labor of love for Hamish: they lived here too—film reels and antique lamps and fixtures, old toys and dusty folios—tides risen to the ceilings. Anna wondered how there’d ever been room for a woman here. There were no traces of her, not on the walls or the bloated shelves, no images in photographs cut in half. It was louder than expected. She followed the source into the hall. It was them: Martha & Friends.

“So good to see you!” they said, as if speaking with one voice.

They were cheery. Quick to praise. Anna did not know this other Martha–the one who complimented her dress. This Martha was…kind. Anna thought she might like the Marthas for a bit, then once saw Anna with Tim and grew quiet, tightening her nucleus and falling in line. She didn’t know what else to say, and Tim shuffled his feet beside her. There again was Hamish, ascending to a blank space on his living room floor, his podium.

“Silence, silence!”

The major of Marthas hooted. “Order in the court! The master of ceremonies is here!”

He presided over them with a full highball glass. They sat in little oblong circles like children playing parlor games. Anna and Tim were split into one circle on the parquet while others clustered opposite, constantly fetching drinks for one another.

“You see,” Hamish gargled. “The reason I invited you all here is that I have had a breakthrough!”

“So far, our inquiries into love have been impassioned and aggressive. Headstrong, like love itself. Our pursuit has been emotional, not logical. When we return from spring break, I want you to have the same kind of breakthrough I’ve had.”

“What kind of breakthrough?” Martha called, more than a little soused.

“You see, I’ve been consulting a therapist,” he said, without fanfare, “and this person has helped me to face traumas I’d just as soon indulge in.”

“The process is called exposure therapy,” he continued.

Anna puzzled over this. She looked around. Martha in particular was rather disappointed.

“Next, we will learn to grow together, not gossip. Last, we grow past our old relationships together to find the missing element.”

Despite herself, she wondered if he was sincere. Was this a real change in practice or another stage of Hamish’s tricks, a setup for public shaming? Because if it was true, if he planned to dissolve them with alcohol and psychotherapy, it was not a terrible business model.

A hypnotist, he had them there in his palm, in his home, greased and ready for therapy.

“I want you to take a sheet of paper now,” he began. “I want you to write down the name of the last person who broke your heart, and I want you to write them a letter.”

Hamish explained the directions in full, his students positively chomping at the bit.

The letters came first. Not her. Anna wrote slowly at first. Her fancy blue pen ate through her paper and soaked into the dress. Fuck. Something about the indulgent bacchanal felt bad to her, forced. Then she felt a hand creep up her back, wet and sticky from champagne. It was Tim, who smiled a hopeful smile at her. An awful smile, one that sprang her forward onto slick socks.

Where were her shoes? She excused herself, murmuring something about the bathroom. She exited the room into the hallway, passing a whole three centuries’ worth of books.

She sat on the toilet for ten minutes before the knock—Martha and her friends. They were very worried! They recognized the difficulty of the process. Maybe they had observed Tim, his wandering hands, or maybe they offered helpful girl talk. Anna felt bad for Tim sitting alone out there, then felt bad for feeling bad. She was allowed to dislike a hand on her.

Then came Hamish’s deep, inquiring voice. Just as Anna collected herself, ready to emerge like nothing in the world was wrong, Hamish entered. He crossed the threshold, pushed her back in, and clenched the doorknob behind him. He loomed a foot taller, arms crossed bigly.

“Everything all right?” he puzzled.

“Great,” she said.

He inclined over her, skeptical. He knew she was lying, not for the first time. Hovering by his sink, she wondered if she might feel the caress of a hand on her body for the second time.

“You don’t talk much, do you?” he said.

She defended herself. “I talk a lot.”

“No,” Hamish said. “Not anymore. You’ve changed. What I mean is, everyone else likes to hear themselves go, but you stopped early on. You don’t like talking about it. Are you afraid?”

“I’m not afraid.”

“Because if so, it’s normal.”

“Well, I’m not.”

“Exposure therapy tells us to picture your fear,” he said. “I want you to close your eyes. Imagine his face. Imagine if he were here with us right now. What would you say to him?”

Hamish the meditation leader closed his eyes. She chose not to close anything. She would not let herself cry. Not here. It would be absurd. She did not want to remember Patrick like this: in this room, with this man. Instead, she repeated his throaty hums. She thought of her entire class outside, listening to her hum in the bathroom with a professor. Then she blurted it out.

“I’ve never been dumped before,” she said. “I lied to you.”

She feared the rest of the story could unfurl with a kind of downhill gravity. But it didn’t. He smiled. Must’ve known along.

Hamish licked his thin lips. “You can join me outside.”

Surely he’d got her now: he would share her betrayal with everyone. But he didn’t say a word. She followed to the living room where she sat crouched with her cocktail dress under her legs. Tim had moved five feet away, scared to look in her direction. She wrote nonsense until everyone had finished. She made like she was returning to the bathroom again, folded the paper in her purse, and absconded before the second phase of the night began.

It got colder: an early March resurgence. She felt silly entering the party late, but only the spoils remained: her floor a boneyard of crunched beer cans. Tonight she was alone, nearly. A girl vomited a punchbowl’s worth into the basin of the coed toilet. Showering, only smelling a little like puke after wrestling the girl into bed, Anna wondered what to do next. She couldn’t just drop her last class—the one that bought her a diploma and a ticket to the real world. But she couldn’t participate, couldn’t talk to Hamish anymore. Worse than pretending that nothing had happened? Telling the truth. So she decided. She wouldn’t participate at all.

She withdrew from the class figuratively, if not literally. Trained in invisibility at the college level, she disappeared from the room as if the individual letters of her name had gone from the roster one by one, Ann-. For the next class, she arrived only on time and not a second before. She spoke to no one. If the Marthas were curious, they dared not trespass. She was as toxic to them now as any nonbeliever. In the moments they deigned to think about her, instances that disturbed their new Buddhist peaceability, they actually felt bad for her. There was a certain freedom in this wide berth, her position at Stoddard as pariah now restored. Hamish too did not worry himself with the recalcitrant. The only person who seemed to care was Tim, who gave her the sallowest looks in their Oscar Wilde-Alfred Douglas class. Just as Wilde’s libertine beloved had sentenced him to prison, taking his legacy and resigning him to a life in shitty Italian cafes with stacks of plates and a lengthy bill in need of liberation—well, Tim looked about as cursed, which made her feel about as guilty.

Oh, the drama in thinking she’d ruined him! She felt in his betrayal a loneliness she understood. As he sat there all surly in his cable-knit sweater, she decided now wasn’t a bad time to befriend him after all.

She caught up with Tim on the street, on what had been their walk.

“To the dungeon?” she asked.

Tim gave her the once-over. He groused.

“Can I go with you?”

She was delicate with him. His eyes were saggy and deep-set—hang-dog like the body on the cross. He acceded, and they loped in silence together with him as leaden as ever.

He started. “Listen, that was a bad time to—”

Anna took his hand. “Tim, don’t worry about it.” She pointed at a couple on the street, two blond undergraduates who emerged from Campus Creamery with triple-scoop ice cream cones, exchanging them not like some spontaneous action but the very biological coordination of mating itself, Darwin’s plot laid before them as interlocking trees and animals are patterned high above and below.

Tim looked at them, not quite understanding. But she needed Tim to know that she would not love anyone for a long time, or potentially ever. Not like that.

He sounded tender, not entirely disappointed.

“I sorta figured.”

He sighed. Anna wished the class would talk about real love instead–the love that comes after young love, the mature love of wrinkled olds who married to their local limitations, who accepted that passion, flirtation, even love would mellow into something like mutual respect and Zenlike caregiving. But no! To her classmates, broaching of love as anything but salvation and bliss seemed an affront to its star quality. Nobody wanted to admit they had aged out of young love, or were about to; that time, the worst of boyfriends, had dumped them as suddenly and callously as their ex, had shipwrecked them on a beach of broken people now broken-up-with.

“How’s your project?”

“Undecided,” she sighed. Which was true, her faith so recently shaken.

Tim still had no idea what the project was, only that she had worked on it daily. But she hadn’t set foot in the lab since Hamish’s party.

“I’m, like, balls deep in mine,” he said. “Still don’t know where it’s going.”

They stood in the doorway of the lab, the very place where she’d once delivered Patrick his foam lattes or greasy falafel, or else a premade burrito that reeked of the campus freezer. She did not know what to do about Hamish, but as she thought of the materials inside the cooler, Tim granted her that thing only a Lab Manager can grant.

“Go work.”

The class was surprised to see her with Tim again. That week they discussed Frida and Diego, the Marthas changing the narrative: their quietest classmates were actually two re-married artists, sexually frustrated but artistically betrothed, wed only in sensibility. Anna didn’t care. She depended on Tim to keep track of things now that she had emotionally checked out of the class. Hamish kept pushing back their final project fandango to make room for idle chatter mostly his own. He delayed any real “grade” talk until the end of the semester was upon them—and it soon was.

All semester, nobody had turned in a single paper. Instead, they wrote weekly assignments with their mouths, little bon mots about Hemingway and Gellhorn—or worse, Anais Nin and Henry Miller—that earned them mental checkmarks. The Miller-Nin letters were so dripping in romance that they were actually dangerous for people like the Marthas, setting a new gold standard of adoration. Anna was over it by now: she saw Henry Miller for who he was, a pugilist man-child who forgot how to love as soon as the couple had returned from Paris and his novel had gotten a bad review. Their letters had taken on an entirely new tone. Mothering! Blech. Martha was undone by this separation. She asked rhetorically, “Why did they ever leave Paris?”

Now that she waged her silent protest, Anna began to worry that Hamish would eventually fail her for what she’d done, which was very little. When the sign-up sheet for the final project came around, she’d left a blank space there, unsure what to say.

“You’ve done nothing?” Hamish asked. “Or the presentation is called ‘Nothing’?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know what it’s called.”

“How about ‘Untitled’?”

As he wrote that down, even his brow had turned from her. Perhaps he’d already decided to fail her. He knew the project was moot, or else he assumed she was faking and egged her to the funeral pyre. Anna would not betray that her project felt half-done: last week, she nearly ruined the footage trying to make it sound right; now there was no sound at all, Patrick rendered mute. She could not decide whether to scrap the project or start all over. Perhaps if she cared more about the class she would restart, or try even harder, but for now she was stuck.

“’Untitled’ is great,” she smiled. “Thanks.”

◆

Living in the dorms, you felt the end the semester more acutely. It was a car driving in reverse at 80 mph: you could not see where you were going, and you panicked about exams, internships, apartments, and you cried from stress or the loss of everything. Still the result was invigorating, bittersweet, and it always arrived before you knew it.

The atmosphere in class was no less manic. Students responded to the final presentation like a star-spangled event. They came dressed to kill, as if absent lovers stood trial here. Martha wore a skimpy jumpsuit with a bikini top—Anna had inspected the tag, it was a swimsuit dry as a bone—and Hamish was fashionably late of course, arriving with deluxe refreshments that surpassed the usual soda and cheez-doodles. Instead, he dropped a case of wine on the seminar table. A bottle per every two students: Anna shared with Tim, grateful she had someone to balance the Dixie cup while she poured. Meanwhile Hamish’s load-bearing smile belied a truth only thinly disguised: he would get the best student evaluations of his life.

Tim had brought the setup from film lab. She had followed, a velvety speaker tucked under each arm. His film was called The Winter of Us. He shared the concept with her six times, but she could never remember it for dreaming about her own. She pictured her little movie debuting on screen, its secrets finally unfurling. She had stayed in the lab from 2 AM until sunrise and still could not make Patrick talk. So she decided to make the kind of lazy artistic choice that passed for sophisticated: she would let the film speak for itself. The 16mm projector was slight and handheld but still mechanically baroque, as articulated as an ancient loom. Anna had tag-teamed its assembly with Tim, making careful notes on where to sprocket the reel, where to place the aperture so it stayed in line. She did not want to rely on Tim when her time came.

“And so, we come to our end,” Hamish said.

The assignment held an atomizing power. Unstable energy ran wires through the classroom. Students budgeted their attention away from Hamish for the first time. Even Martha felt impenetrable beyond the myopia of stage fright. They were inaccessible, submerged in their little diving bells of anxiety. Anna found Hamish making direct eye contact with her first time in months. He spoke of the dissolution with course evaluations in hand: their divorce papers. Anna wished he would file them right now. Why had she even come? It wasn’t like Hamish would have a reason to pass her, with the project gone haywire at the last second. The class had been a disaster, and now her film was. She needed only to survive the other presentations, then her own, before she vomited a generic evaluation and packed up her dorm room gone inside-out.

The projects detonated one-by-one, their makers proud and embarrassed. Shallow in the way of “confessional” art. Martha’s project, EKG, was about the electrocardiogram taken moments after literal heartbreak: he had dumped her at a coffee shop, and so she had chugged two coffees and suffered palpitations so distressing she’d hobbled to the infirmary with presumptive heart failure. CODE BLUE! Even Tim’s Winter was a self-pitying opus. Snowy images appeared then saturated on screen for minutes, as if he strove to turn white into the darkest black. Hamish found things to love in these sophomoric displays. He nodded to the beat of their misery, midwifing their pain into catharsis.

When Anna’s time came last, she took the stage without fanfare. Let’s get this over with. Others self-deprecated with careful preface, but she had prepared no speech. She stood by the projector divining some sense from her notes. It felt like people had forgotten she was even here, and collective memory filled the room. Tim’s mouth gaped, confused, as she palmed the small reel from her briefcase.

“This is a silent film,” she said, and shrugged. She had tried. Action!

The silence was painful at first. The class sat in knots. On screen, a mystery was mounted then solved. Patrick–there he was. Students clucked at his handsome face in the way they had with others: finally, this was what they looked like! But he was the most handsome, not that she would accept a prize for him. Just that he was pretty you wanted to see more of, and they seemed hooked. She had not expected the silence to draw them in.

Anna had created intertitles where images would not do. Brice Patrick “Pat” Dawes, Born 1967. Then footage of the childhood home at sunset: his old playroom in the gloaming, his empty bed in light sunspots, his old rocking horse. Then the Together era: Met 1985. Outside featured a video of her dormitory. Girls from her floor stood in line for a hall meeting, wearing curlers and thick glasses, swarming her for stories. She remembered their faces, now gone.

Next came images of a beach trip: a joint family vacation with both their parents on Block Island. There he was, dressing her brother in sand. There he was, buying a pair of beige dockers that matched hers. The next scene captures on the pathetic excuse for Rhode Island dunes, a photo snapped after a round of family portraits during which someone’s mother realized: Oh yeah! You two! Her brother took the video camera to film the photograph behind-the-scenes. Anna and Patrick smiled like two criminals with a secret: they are at that moment when love has supplanted the family at last, and a mother fails to realize her usurper is a little girl more important than she.

Then the final page: Died 1989. It elicited a slight gasp, which she ignored like a speed bump. The footage darkened only slightly. They saw more of him alive. Patrick in his saggy winter gear, bending to pack a snowball he was barely strong enough to throw–at her, as she laughs. Watching it, the class cackled too. Good. She wanted people to laugh. More than anything, she wanted to display the sweetness. To laugh at these things again.

Then, abruptly, the last scene worked as planned. Sound entered the room. People gasped, the projector screaming.

“Sorry,” Anna said. “Sound here.”

This was her favorite moment in two year’s treasure, the only part she wanted sound for. And so why, at the last minute, had she decided not to include the whole thing? Anna had killed her darling, she had left it on the cutting room floor, like a memory she has decided to keep for herself: In the footage, she has made breakfast in bed for her sick beloved and carries it out to him. Eggs, bacon, and toast on a platter so hilariously large he isn’t strong enough to hold it. She passes him the plate and he struggles. Nearly buckles under its mighty weight. For a moment it even looks as though he’s fighting back tears. Anna stands idly. Her training kicks in. Let him do for himself, goddammit, no Mom interventions. But she remembers getting scared too, and actually sees herself start to intervene: the worry registers on the face now foregrounded. “Here, let me!” Then Patrick snorts, throws his head back, and screams mightily. She is terrified. She recoils as if from a gunshot, throwing her hands up in self-protection as he sneezes on the platter she’d spent an hour designing. It takes them a moment to realize: the food, each molecule a protein or carbohydrate meant to restore him, now soaked and ruined by snot and spit, and they are lost to stitches. They are thrilled by these happiest of accidents, by these little detours in life.

Then the film cut to credits. Anna sighed, not knowing she’d dreaded when it was over.

Now she waited for a response. Tim was the first to stand. Martha and Co. followed swiftly. Hands clapped like beaten erasers. Their reaction surprised Hamish, who was waiting, pursed thin red lips, a judgment nearly rendered. The rest of the class had turned to him, watching him now, waiting for him to praise Anna, or something.

Let him, she thought. Let him decide. If this is heartbreak. If it’s real.

Did she pass? Would he take pity on her? It felt like they were back in the bathroom, Anna standing a little taller now, unafraid of his husky breath, his sausage fingers, except this time the other students had rallied around her; she felt them there. What would he do now that she had the power?

Anna looked away. Sort of didn’t want to know… She could always stay another semester if she failed. It wouldn’t be so terrible, but of course it would be. So she turned from the black projector screen and looked Hamish straight on. Better late than never.

He smirked, mouthed Well done. Then he winked, because of course he had to ruin it.

Anna tried not to show relief, but of course she felt it. It was over. She returned her gaze to the black screen that spun the final inches of cheap film. The movie ended, just in time for her little post-credits scene. She felt relieved enough to enjoy it.

It was just the two of them—her and Patrick again on screen—he’d gotten her here.

She’d added a little bonus blooper reel after the sneezing, the one part where she hadn’t shredded the sound off the film. Sound screamed back into the theater: she and Patrick laughing hysterically while flanked by a griddle of food.

It wasn’t particularly funny, but it was to her. There Patrick is alone, yelling his gratitude from bed. The last lines belong to him, frozen on his body as she goes to the kitchen for a second plate.

“Thank you,” Patrick calls out to her, laughing. “Thank you, thank you, thank you!”

So that was it, Anna smiled.

“Thank you,” she said.