I conclude this week’s virtual therapy session, like always, lamenting my life’s lack of meaning.

“I just wish I was doing something more noble with my time,” I say.

“You don’t find your work spiritually fulfilling?” asks my therapist.

I tell her no, I don’t find my work spiritually fulfilling.

“Do you have a friend or colleague who does something that you feel is noble?”

“My friend Laura Cohen. She’s in med school.”

“And you consider this noble work?”

I don’t know. I haven’t spoken to Laura Cohen in three years. I assume, based on the amount of social engagements she misses, that her work is spiritually fulfilling. Through the reflection of the screen in her glasses, I can see that my therapist is online shopping. I don’t mind. Her services are covered by my insurance.

I live above a fish market in Chinatown. East Broadway smells like hot blood. Except in the winter when it smells like cold blood. You can buy anything in Chinatown like lobster or crab or squid or shark fin or PCP or a fake Burberry sun hat. I have never been to regular China. For breakfast I pop a handful of pistachios—a highly-caloric nut—into my mouth, chew, then spit them out into a dish towel. Then I fill a dropper with 6ml of Metacalciquin intended to increase metabolism and shoot it down my throat. I do this every day. I find that it’s best to do the same things every day to avoid decision fatigue. My vision blurs for about ten minutes, a common side-effect of the Metacalciquin, so I make my way to my desk by groping the walls.

I work for a marketing agency called Fresh Start. Our business has a focus on reputation laundering, which is to say, we take on clients who for one reason or another fell out of public favor and are looking for brand reinvention. The Fresh Start logo is an optical illusion or “ambiguous image.” You might at first see a beetle, dead on its back, but turning your head reveals a phoenix rising from its ashes. We pioneer campaigns for the likes of Solomon hand guns—now with a smaller grip for kids!, campaigns to reinstate Columbus Day, campaigns for dating apps with a focus on age-gap relationships, campaigns to lessen concern around the opioid crisis, campaigns for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ivory-poaching, crypto-fascism, factory farming, accused sexual predators, the recently incarcerated, puppy mills, fracking, lead-heavy paint companies. I have been working at Fresh Start for just under a year. For my anniversary, I hope they give me a new desk chair.

Xian texts me that he enjoyed our time together last night, which I assume is a formality. I met Xian on a dating app for young people living who out of financial necessity live in the ethnic diaspora of an ethnicity to which they don’t belong. He lives in Little Ethiopia. Yesterday was our third date. I thought he was taking me to the Met. Instead, he took me to a Stanford Prison Experiment themed escape room. We then held each other briefly outside of my apartment before amicably going our separate ways. I have not found much success in dating, which I attribute to a hormone or chemical lacking in my skin. Skin contact is incredibly important in intimate relationships—at least that is what I learned from The Science of Intimacy, although its writer, who also penned The Science of Marketing, has no discernible scientific background. I learned that there was a hormone or chemical lacking in my skin when a friend and I visited a spa in Mexico where you place your feet into a terrarium of small fish. I remember the proprietor kept referring to the fish as her little soldiers in Spanish. I watched as her little soldiers swarmed my friend’s feet, eating small continents of dead skin off of her heels. But when it came to my turn, the fish did not eat my foot skin. They swam to either side of the tank, collectively affronted by the intrusion. “Maybe they’re full,” I had suggested, but the proprietor just looked disturbed.

I enter the “waiting room” for a video meeting with my boss, Dorian. While in the limbo of the video stall, I browse the internet and get a pop-up ad for a small defense lawyer. If you or a loved one has taken Metacalciquin you are entitled to financial compensation. I click the ad and skim its contents. 1 in 4 regular Metacalciquin users lose their sight permanently. Dorian interrupts my reading with an overzealous hello. His enthusiasm for marketing is unparalleled. Dorian’s video background depicts an apartment much nicer than his own, his silhouette disrupting its continuity when he gesticulates, which he does often. He tells me about a new docuseries that explores the social habits of field mice, the immense detail of his account quelling any need for me to watch it myself, had I the will to watch television. His video background changes to a beach in Malaysia. Or maybe Vietnam. Large, jagged mountains protrude from the digital water. I have never been to Malaysia nor Vietnam.

“We have a super exciting new client BUT I am going to need you to come into the office for this one.”

“We have an office?”

“We have an office!”

“Why do I need to come into the office for this one?”

“It’s so not a big deal at all but I’m going to need you to sign a multilateral NDA.”

Outside my window, I see a woman tending a fire in a metal trash bin, periodically sprinkling the flames with fake money. Sometimes they do this, my neighbors, as a way of sending wealth to their deceased in the next life. I wonder if the residents of this ethereal Chinatown notice that the currency isn’t real. Perhaps fake money works in heaven.

On my way to the office, which evidently is and always had been south of Houston Street, I walk into a pizza shop and order the greasiest, most toppings-laden slice available. I eat it too quickly to detect any one specific flavor, then think about what I would take with me were my apartment to catch fire. My selections—laptop, passport—are out of convenience rather than sentimentality. I only have a brief window of time before the pizza digests irreparably into my system so I induce vomiting outside a Polish church.

Dorian meets me at the door of the office and gives me an unsolicited tour. The office is in a restored factory with a cage elevator that shakes as it ascends. Dorian points out details in the crown molding. I realize that I have never seen the lower half of Dorian’s body. In my eleven months at Fresh Start, we have never met or expressed any interest in meeting.

“This chandelier is from the 1490s,” says Dorian.

“Doesn’t look a day over 1460,” I say.

“Ha!” says Dorian instead of laughing.

We settle into a large conference room. The walls are decorated with generic modern art. Muted swaths of color. Mass-produced Rorschach tests.

“What do you see when you look at this?” Dorian asks of the amorphous blobs.

“Amoebas,” I lie.

“I see a slave ship on a choppy sea. Two lovers escaping religious persecution. A man castrating a horse.” Dorian hands me the brief which is extensive and bound with brass fasteners.

“It’s in Arabic,” I say.

“That it is. That it is.”

Dorian fans an NDA across the marble desk. It is also extensive. A non-disclosure novella.

“These folks are more sensitive so before we get into the nitty gritty…” Dorian produces a pen.

“I think I might need a lawyer.”

“I can tell you this: the client wants an entire rebrand. Lots of opportunities for creative innovation.” Dorian pushes up his sleeves to his elbows as though he’s getting ready, physically, to create and innovate right here. “We’re looking at an exclusive partnership.”

“With whom?”

“Are you familiar with any jihadist rhetoric or the literal implementation of the Quran in general?”

“What are you talking about?”

Dorian checks over his shoulder. The office remains empty. “It’s Islamic fundamentalism with a new flair.” He spreads his fingers apart to make a little firework.

“Instilling the fear of God in a modern audience.”

“I’m sorry, but…”

“Don’t use apology as a disclaimer. It’s a subservient feminine quality and I like to think of us as equals.”

“Dorian, I don’t think we should get involved with the Islamic State.”

“Why not? They want to triple our day rate. You just may need to cover your hair, nose, and mouth in future client meetings.”

“It’s objectively wrong.”

“You’re being a tad close-minded.”

“Am I though?”

“You’re writing the narrative,” says Dorian. “Wrong. Right. It’s all fictional. It’s whatever you make it.”

I stare at the office art and, for a moment, I can see a horse. A sea.

“What is it that you think we do here?” asks Dorian.

“We’re a creative marketing agency,” I say.

“We’re in the business of reality production,” Dorian corrects me. “We don’t tell people what to think. We tell people how to think.” He’s getting animated in his motion now. Gesturing more. Blinking less. “Guy Debord—are you familiar with this fellow? He’s really worth a Google!—Debord said, ‘I wanted to speak the beautiful language of my century.’ Do you know what that language is?”

“French?”

“Advertising! We are speaking the language of the consumer. We’re waxing poetic to the everyman. We don’t just supply content to hedge fund managers and South American war lords. We are the premier gateway between truth and individual.” He pats the backs of two chairs, as though truth and individual are currently in the room with us.

“Marketing is the bedrock of late capitalism. As a junior strategist, you are the arbiter of twenty-first century America. You hold the keys to an empire, albeit a smaller empire than say my empire but an empire nonetheless. What do you want to do with those keys?” Dorian makes a pyramid with his thumbs and pointer fingers.

I tell him I am going to need the rest of the day to think.

◆

When I get back to Chinatown, Xian is waiting outside of my apartment. This would constitute our fourth date though we did not have previous arrangements to get together and this spontaneity prickles me. Not a bad prickle. The way I can only imagine it might feel to have one’s feet nibbled by fish at a Mexican spa. Xian unpacks a bag of groceries and says he is going to make gratin dauphinois. I don’t know what gratin dauphinois is but I know that I will need a suite of vitamins to help me digest it. I catch Xian staring at my winter boots.

“It’s odd,” says Xian, “that you wear leather but don’t eat meat.”

I tell him that my vegetarianism is not moral but dietary.

“I understand that nihilism is in vogue for your generation”—Xian delineates between my generation and his as he is seven years older—“but there must be something you find meaningful?”

“What do you find meaningful?” I ask.

“God, French cooking, the way the sky changes from summer to fall.”

As Xian cooks, I excuse myself to the bathroom and call Laura Cohen at the New York Presbyterian School for Medicine and Medical Research. I ask her if she has ever been out in a public setting, say a cafe or train station, and witnessed someone collapse as a stranger yells, “Is anyone a doctor?” and has she, Laura Cohen, gone to their aid?

“No, thank G-d,” says Laura Cohen. “I don’t think that happens as much as you might think.”

“What’s new?” I ask.

“Not much. There are microscopic shellfish in the New York City tap water,” she says.

“That seems like it should be a bigger problem for the kosher community,” I say.

Then I ask Laura Cohen if she is spiritually fulfilled.

“I guess,” she says. “I gave a late-term abortion to a woman in Buffalo last week.”

I sense Xian listening at the door so I turn on the faucet.

“So, what are you doing these days?” Laura Cohen asks me.

I tell her that I’m the arbiter of twenty-first century America.

“That’s cool. Well, nice catching up with you.” Laura Cohen hangs up and I stare at the water as it pools in the sink, inspecting for tiny shellfish.

I wake up to the distinct clang of a Chinese funeral proceeding headed down the block. This happens about once a week. Xian is asleep next to me, still wearing the clothes in which he arrived. I climb onto my fire escape and watch the grieving men and women plod solemnly down East Broadway. Listen to their melancholic instruments being blown and strummed and picked. Little children carry whimsical flags after the casket. Xian stirs, comes to the window and looks at me.

“Are you crying?” he asks.

“Oh,” I say. “I guess so.”

◆

“You came back,” says Dorian when I come back.

` “I knew you’d come back.”

“It was touch and go there for a while.”

“Come in. I just ordered coffee. Can’t figure out this machine! Too many bells and whistles in my opinion.” Dorian glares at a twelve-hundred dollar espresso machine. I dawdle in the mouth of the elevator. It occurs to me that we are the only two people in the office for a second day in a row and I begin to wonder if anyone else works for Fresh Start.

“I have some stipulations,” I say, “for the direction of the campaign.”

Dorian smiles and ushers me inside. Despite the office being empty, he shuts the conference room door behind us.

“Alright,” he says. “Pitch me.”

“What do religious extremists in their early twenties have that we don’t have?” I ask.

“Less premarital sex?”

“Something to believe in.”

Dorian nods, sage-like.

“If we’re going to make terrorism palatable to a contemporary market, we’re going to need to shift the discourse a little. I’ve added some tenets to the brief.”

“Body-positivity. Climate consciousness. Gender-affirming,” Dorian reads aloud. “Monthly donations to the Anti-Defamation League?”

“And triple my day rate,” I confirm.

“You want to incorporate the ideology of neoliberalism into Sunni Islam.”

“This is, as they say, my hard line.”

“I like to see you taking some initiative,” says Dorian.

He lays out the NDA.

“Daniel Ortega—a client of ours!—once said to me, ‘you go to sleep with the boys, you wake up with the men.’ A funny line from someone actively trying to discourage homosexual accusations but I think it applies here.”

He plucks a pen from his jacket pocket.

“Are you ready to wake up with the men?”

I sign the papers, relinquishing my right to share any details of our work on the project digitally, verbally, or otherwise.

Dorian takes me out to celebrate. To get to the bar of his choosing, we must walk through a travel agency which is in the back of a nail salon which is in the back of an underground mall. The room is dark and smokey and music pulses from within. Dorian orders two shots that come on fire. His whitened teeth glow in the darkness. I briefly imagine Dorian murdering me, standing over my prone body with that same unflinching smile. I try to text Xian but there is no service.

“No service,” says Dorian. “That’s why it’s called Off the Grid. Isn’t that fun?”

“Really fun,” I say.

“Let’s make idle chit chat. What are your hobbies? Do you have love in your life?” Dorian asks. “I’m not being fresh, by the way. If you can’t tell by my attire or vocal affect, I am unflinchingly gay. My boyfriend’s a psychopharmacologist. Pablo.”

“Doesn’t it make you feel bad,” I ask. “The work that we do?”

“Why would it?”

“Isn’t it contradictory to what I assume, as a gay socialist, are your core values?”

“I’m not going to sit here and tell you that right or wrong have any purchase in the greater scheme of things.” Dorian takes his shot. “Do you know what it was like growing up in Durham, North Carolina? They used to run up to my dad and sing ‘don’t let your son go down on me’ to the tune of—”

“No, yeah I get it.”

“My primary assailant was a kid called Tadam Biddle. Do you know what Tadam is doing now?”

“What is Tadam doing now?”

“He made a fortune in crypto. Lives on a houseboat.”

I stare at Dorian or the teeth that are Dorian in this bar. Noting my lack of enthusiasm for the drink, he downs my flaming shot. I am not a big drinker because alcohol is highly-caloric and causes a significant disruption to my routine. I ask for a glass of water and Dorian orders another drink.

“It doesn’t matter,” says Dorian. “We’re all the same,” his voice slurring with imminent inebriation.

“And I don’t say that fatalistically, I take comfort in it. You, me, Tadam Biddle,” he gestures outward, vaguely towards the streets of Lower Manhattan. “Working stiffs, housewives, school children, church-goers, the upper class and middle class and—what are they calling it now?—working class, but then more specifically widows and illegal immigrants, truckers and people with masters degrees, drifters, retired landowners, sovereign citizens, teamsters, the mentally insane, ambulance chasers, girlbosses, teachers and nurses, protesters, Southern aristocrats, temps, sex workers, Satanists, the young and beautiful, intravenous drug users, the people who stand outside of art galleries, industry plants, Canadian jocks, rust belters, foreign heirs, Hasids, carnies, plastic surgeons, men with Napoleon complexes, engineers, podcasters, the terminally ill, Holocaust deniers, terrorists, kings and queens, in the monarchical sense not the colloquial one. All the same.”

“What are you?” I ask.

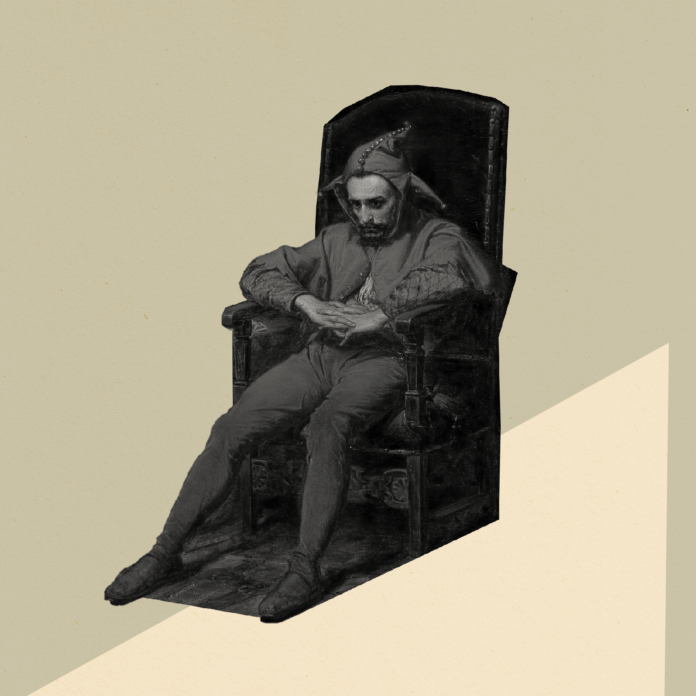

“Easy,” says Dorian. “I’m the jester. My societal role allows me to speak truth to power. I’d say you are too but you don’t seem to participate in enough self-parody.”

“I can make fun of myself.”

“Alright, then you’re the jester too. Cheers, jester.” Dorian clinks his drink with my water glass which the more superstitious consider to be bad luck.

◆

The weeks slip into months fluidly as I focus on my “work-life balance.” Xian and I continue to see each other. I once heard or read, though I have long forgotten where, that your time alone prepares you for the time when you have love in your life. I try to reflect on my time alone but cannot draw any conclusions from my past. Like receiving fake money in the next life, it’s of no use to me here. Xian doesn’t seem to sense the missing chemical in my skin. We have been intimate now, including several ways that cannot lead to procreation so I know that his motives for being with me are more than purely biological. I have gone out with Dorian and his psychopharmacologist boyfriend Pablo on several occasions and to several inconveniently located but no doubt upwardly trending bars. On Tuesdays I play mahjong with my downstairs neighbor. The game is complicated, almost intentionally so, but I am learning quickly and I like how the little tiles feel in my palm.

The increase in my day rate has allowed me to employ a better therapist and purchase a new desk chair. I once read that even the subtle improvement to one’s daily posture has immeasurable effects on one’s mood. I assume these immeasurable effects are positive. I also bought a weekend getaway to the Poconos with which I plan to surprise Xian since he seems to have a penchant for spontaneity. I have this daydream, this fantasy, that we will spot a little house in the country, dilapidated—reflected in the price—but charming, a “fixer-upper.” We’ll purchase the house and live out our days somewhere rural and in close proximity to a stream. Then, if I entertain these fantasies long enough, I win a prize for ethical marketing. Xian opens a restaurant, Parisian-Pennsylvanian fusion. We will feel a sense of great peace.

One evening, while Xian is preparing a roux (“the basis for all French cuisine!”) I dial my soon-to-be-doctor friend Laura Cohen. I tell her that I miss her. I tell her that I have made improvements to my posture and am entertaining a sense of great peace. I tell her that I have been seeing someone and he’s currently in my kitchen making a roux. Laura Cohen says that she’s happy for me. She says that she too is seeing someone, engaged to him actually. He’s also a doctor from a long line of doctors and his family is throwing them an engagement party at the Plaza on Saturday and I may attend if I like.

Dorian calls me early on a Saturday. At first, the call incorporates into my dream. It’s a Chinese funeral proceeding. The instruments are spouting my ringtone.

“Buenos días! Why are you whispering?”

I tell Dorian that I am whispering as to not wake Xian who sleeps next to me on his back like a sarcophagus.

“I’m calling from Mexico City. Roma Norte! Pablo and I adore it here and have decided…we’re going to stay! We’re seeing the cutest house this afternoon. Colonial revival. And the price of living—”

“You’re moving to Mexico?”

“Si! I will be handing in my resignation to Fresh Start on Monday. If asked whom I might want to succeed me, I will name you. All of our clients are so taken with your work, it shouldn’t be a problem.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Did I stutter? I’m genuinely asking. I’ve had quite a bit to drink already.”

“You’re quitting the agency and moving to Mexico.”

“The keys to the empire are yours, Jester. If you want them.”

Dorian hangs up and Xian shifts in his sleep next to me, instinctively moving closer to my body which, as I’ve said, does not repel him.

The grandiose lobby of the Plaza hotel reminds me of Versailles or the Kremlin. This comparison, of course, I am basing off of depictions because I’ve never been to France or Russia. But soon, I will have been to the Poconos. Making my way into the Tea Room I see Laura Cohen, surrounded by twenty or so doctors and their respective spouses, sitting next to a nebbish young man who is presumably her husband-to-be.

I settle on one of the quips I plan on using to open conversation.

“I hear the third leading cause of death in America is medical malpractice,” I say.

“What?” says Laura Cohen.

“It’s good to see you and congratulations.” I hand her a pink box.

“They’re macarons. I got them in the lobby gift shop.”

“Thanks. Yeah, it’s wild.”

“Laura..?”

“Oh, his last name is also Cohen.”

“Are you sure you’re not related?”

“Yeah, we checked. Do you want to meet him? Felix—” She taps the man next to her. He’s performing surgery on a caviar-topped tartlet with a little silver spoon. We shake hands and he offers me a glass of champagne. I pretend to sip it out of habit and then actually sip it and the liquid warms my entire body.

Felix stands and is so soft spoken that at first I don’t even realize he is delivering a speech.

“My heart, it’s no longer my own. Perhaps I’ll pivot into cardiology to better understand how she did it. Doctors, practical people that we are, like to make sense of things. We take comfort in organization, regime, strategy, etc. But at the end, and I have seen people at the end, crossing over into the next leg of their journey—I apologize for the morbid turn this has taken—but see, at the end, little else matters except, well. Love has helped me see beauty in senselessness. I’d marry you a thousand times Laura Cohen—to whom I am not even distantly related [pauses for laughter]. And even though I have palpated 3 different rectums today, you would be hard pressed to find a luckier man alive.”

Everyone in the vicinity raises a glass.

“Congrats to you both,” I say and stand to take my leave.

“Thanks for stopping by,” says Laura Cohen. “And it’s cool you got that terrorist organization to participate in affirmative action or whatever. They seem to be doing a lot of great work for the community. That was you right?”

I mime zipping my mouth shut and head out of the Tea Room. A clatter of glass and silverware draws the party’s attention to a table over where an old man has collapsed. He’s choking, perhaps on a cucumber sandwich or mille-feuille. His distressed dining mate, an elegantly dressed and significantly younger woman screeches, “Is anyone a doctor?” Everyone at Felix and Laura Cohen’s table stands. I make my way to the foyer and out the revolving door.