Driving north on the island road, they were mostly innocent. They’d done awful things, but the sort of awful that from a distance looks like resourcefulness and might even—at a seafood boil, in a certain crowd, after several drinks—offer some allure. One worked as an attorney for the oil company responsible for the Deepwater Horizon spill. One sold her child’s baby teeth, wiggling them loose prematurely with her thumbs. One raced oil trains on the mainland for dare money, her siblings shouting encouragement from the truck bed. In the last race, right as she crossed the tracks, her younger sister, Lena, bounced from the truck bed onto the track and was sliced into three by the train. Heading north, they thought they’d left those things behind them. On the island road, they drove like fishermen, fast enough through the standing water to leave a double V wake, sounding the horn as if on a gillnetter in the Gulf.

They left for better fishing. Reeled in a snapper the other day with four balls. I’m not eating anything with more balls than I have. For better weather. For better pay. They left because the flood insurance man refused to renew. He said we should think about relocating. I told him the only thing I want to relocate is your jawbone. They left because the dunes were bald, sand fleas the only life on the beaches. Because the road went under with every tide, and one day it was going under for good. They left trees with salt-encrusted roots. They left car frames rusted through by the warm, wet brine. They left the boxing club and stadium, which had never been used. They left the ground broken for an indoor ice-skating rink, the last in a series of projects designed to make their town too valuable to abandon. We made sure we didn’t look poor. You look poor, they’ll treat you poor. They left their best bird dog clipped to a high line in the backyard. They left the Easter crockery. Lena’s sister left Lena’s bed unmade, as Lena had left it. She left the skirt onto which Lena had sewn eight hundred sequins. She left the bowl from which Lena had eaten her cereal the morning she died, the milk hardened at the bottom to a gray plaque.

What did Lena’s sister take? Two things: Lena’s driver’s license with the thumbnail photo. Lena’s name. Lena’s photo looked more like her than her own did. She thought it was little enough to take. She thought Lena would stay behind.

Four-wheelers on flatbeds. Gooseneck trailers stacked with rolls of barbed wire. Carpets with spores of black mold burred in the shag. Danamarie and Salty Mare and Y-Knot. Six meat rabbits in a rusted hutch. A refrigerator with no door. Trap buoys painted in the family colors, bouncing up into the wind like flags. American flags. In the cab, three kids and a dog. A crib mattress yellowed with urine. A wide-wheeled racing chair. Four bottles of Southern Comfort. An oxygen tank. One Ruger 10/22 Sporter Camo Exclusive. A Glock Gen4. A breast pump. Vicodin. An inflatable pool. A duck decoy, carved from cedar. Holy water. A Fisher-Price Stroll & Learn. Mud boots and mudbugs and ice in a foam cooler and insulin and gasoline. All they could carry from the houses left behind them. The houses themselves, they carried in pieces—sheet metal and planks of hard pine and two-paned windows wrapped carefully in shoe paper—from which they planned to rebuild.

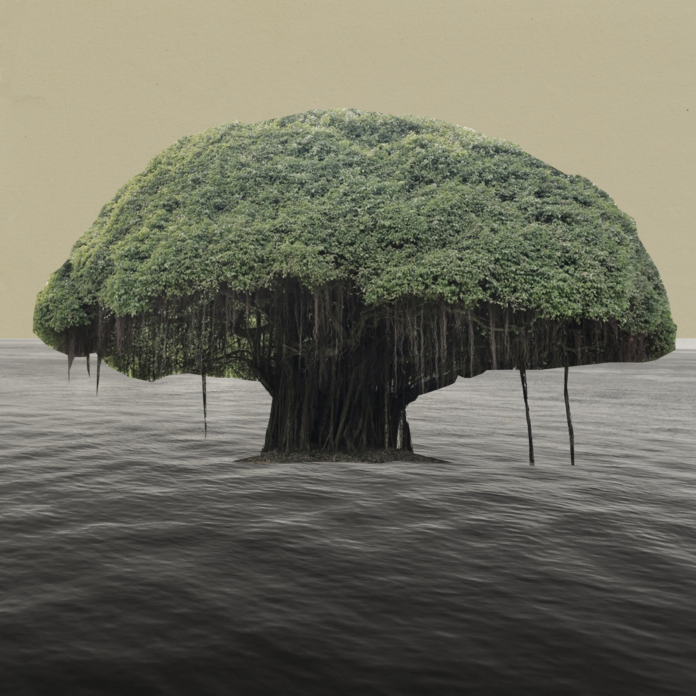

In those trucks, above the beat of air through the windows and the drawl of the radio, they talked about the land awaiting them. They’d printed grainy images from Google Earth of the plots parceled from an old sugar plantation and assigned to them in order by last name. Quarter acre backs up to a creek. Got an outbuilding already. Got a slope to it. They thumbed through copies of Architectural Digest and circled photos of stone-floored basements and game rooms large enough to fit two pool tables. They studied an old Kodak photograph of the shotgun house their great-grandfather built at the turn of the century, which they planned to replicate right down to the square-head screws. They talked about how to stretch the settlement they’d gotten for the stilt-houses they were leaving behind. They imagined his-and-hers bedrooms and dormer windows with pillowed seats and frescoed mantels and tire swings. Lena—she’d taken that name, it was her name now—imagined a room to herself and a bed draped in tulle. They all imagined dancing late into the night on a wrap-around porch. They imagined rivers so thick with crawfish you could scoop up a meal in a bucket, fingers of the Gulf tumbling north, fresh and potable.

Maybe no one had told them about us. Maybe they believed the land they’d been promised to be virginal—a green and empty paradise. Maybe they chose to forget us. Maybe they believed if they refused to think of us, we would disappear.

They stopped only when absolutely necessary. To refuel. To tighten the cables securing mattress to roof rack. To squat in the reeds, tennis shoes on the asphalt, and shit. Loose, watery shits. Giardia in the water, according to the EPA, which some believed and some thought was a trick to get them to take the settlement the government offered. One stopped to take a leak, leaving their water behind in the water. Lena stopped to cast fry nets, which sunk through silt and grew heavy with fish. One stopped to shoot a night heron for their dinner. Most birds, you need a twelve-gauge, but you can drop a night heron with dust. One, who stopped to plug their bleeding with a dry tampon, looked back at the island where an osprey pair circled a nesting tree. For a second it looked like it used to. The island was green, green, green.

Ninety-three miles north, we waited for them. We held a parade for them, to advertise our goodwill. We wore face masks made of stiffened gauze, adorned with deep-set wrinkles and antlers. We brought out our best float from the year’s Mardi Gras—a dragon sculpted from wound wrap. We brought out our best fiddler. Our best wagon. We brought out our replica of the Sears Tower, assembled from Coke bottles we couldn’t return. We brought the hand-cranked wheelchair we’d engineered with bicycle chains. We draped a banner—“Hello Islanders”—across the back of the chair. We held signs—“Refugees welcome.” They honked. They waved. Their children flattened their faces against the windows. They slowed for directions to their plots. They slowed so we could check the pressure of their right, front tire. They slowed to throw a red slushy out of the car window, splattering the hems of our trousers. We’re not refugees. We’re Americans. They stopped to shake our hands. They stopped to quiet their kids, who were clamoring to see us up close. They stopped to ask if there were more of us. We shook our heads. We numbered only sixteen. They numbered sixty-nine. They said they guessed we’d be seeing an awful lot of each other. When their kids stuck their owlish heads out the rear windows, they said, Get back in the goddamn car. They gave us corn bread. They gave us business cards. They gave us the finger. They sped past us without seeming to see us at all.

That first night, in their FEMA trailers, they slept on thin cots with metal frames. They dreamed of riding mowers clipping blankets of zoysia. They dreamed of the cremated body they’d left on the island, dreamed a strong, nowhere wind that tore the roof from their house and slurped the ashes up into the sky. They dreamed of Lena’s severed legs dancing the salsa in black hose with terrible runs. They dreamed the storm followed them here, and the trailer floated off on the waves, and they heard their oldest daughter gasping for breath, choking as the waves curled over her head, and they sat up, still half-asleep, slapping the wall where the light switch would have been if this was really their wall, their house. Their daughter sobbed in the next cot. They lay back again on their cot, which others had used before them, which smelled like the untold tragedies of other people. They turned their back. I’m trying to sleep. That first night, they drank. They smudged with sage. They fisted, fucked just for the familiarity of it. They woke every fifteen minutes to spin the handle on the crank lantern, so it wouldn’t dim and die. They lit three candles to the Virgin, the Mother, and the Beloved, asked for a blessing on this new land. They slept alone for the first time in decades, better than ever before. That first night, they woke up at four in the morning and walked out into the yard, where they saw us move through our lit bedrooms—most of us sleep fitfully, if at all—and they wondered what we were doing and if we were watching them.

We learned how not to call them. Not rednecks. Not white trash. They were Cajun—descended from the Canadian Acadians, who were put on a boat for New England in 1759, and traveled overland from there to the Louisiana colony. This isn’t our first go-round. We’ve been forced out before.

They learned how not to call us. Not lepers. Not cripples. Not contagious, not even those of us with tight-fisted hands or dimpled faces. We had Hansen’s disease, well under control in every one of us. We were barbers and journalists and engineers. We had an American Legion, a Mexican Club, a softball league. We sang choir and visited the school in Baton Rouge and stocked the freshest shrimp north of the bayou in our market. Some of us were American. All of us were Louisianan. We were the daughters of Ukrainian bankers, nieces of British smugglers, descendants of a German armadillo farmer, a Texan hog mogul, a Korean diplomat come to the National Hansen’s Disease Clinical Center for the gold-standard treatment.

Things between us were mostly ordinary. Early on, they came to us for water, their plots having no pipes. They came to us for news. They came to us for seafood, because our crabs were freshest, our shrimp wild caught. Some came to us with decks of cards, and we played gin rummy elbow to elbow, pausing between hands to pour drinks. They drank beer. We drank Bloody Marys, because gluten inflamed the disease. They kept their thumbnails long to cheat. We said, “Baby, be there,” for luck, before every draw. They came with stories. They told us about standing chest-deep in waders in a redfish pond as a water moccasin slicked past, towing an alligator three times its size. They told us about the spill. Most of them had worked it, one way or another—built booms or run skimmers. One had his boat pressed into service for the cleanup. I told them they might as well take my legs, but they only needed the boat. One had tried to outrun a plane spraying Corexit. He’d motored his skiff full throttle, watching the golden, chemical rain sweep the Gulf until it was on him. Burned my eyes worse than Mace. And I know Mace. They told us the man they’d married had been known as the Cajun Fisherman. Best fishing guide on the island, he was. Up here, what is he? They told us all the ways they’d tried to keep the water back from their front porch. All the ways you could fish panfish. All the ways you could run a dragnet. All the ways you could rear a kid wrong.

Lena was the only one who came to us for comfort. She told us how her sister had looked on the train tracks on her hands and knees—like a dog. She told us how she had taken her sister’s name and felt, sometimes, the chill of carrying the name of someone dead. We understood. We also carried the names of the dead. One of us, the story goes, had died in a knife fight in Croatia. Another at the Bay of Pigs. Our families held funerals with empty caskets and forgot us. Lena showed us her sister’s license with the thumbnail photo. “You look just like her,” we said. Early on, we told them what they wanted to hear. We matched them drink for drink, story for story. We told them about the evening we got the jukebox running in the cafeteria and two-stepped until dawn. We told them about our Fat Tuesday, when we showered the citizens of Carville with armadillo doubloons. We told them about the Saturday afternoons when our daughter came to see us, smuggled in beneath the seat of a Lincoln Continental. Children weren’t allowed onto the grounds, and we weren’t allowed off the grounds back then. We told them of the narrow moon nights when we snuck quiet and calm through the garden and the gap in the fence to fish in the river or spend a night over liquor in Baton Rouge or visit family in Puerto Rico. We told them the ugly stories. Two days locked in a sleeping compartment on the Amtrak Sunset on our way to the Home—food brought in on a plastic tray, piss taken away in plastic bottles, not allowed to leave. We told them we couldn’t have children anymore. We’d been sterilized by the disease, by the knife, by time. The ones like us who came after us, who caught the disease now from their brother or an armadillo, would never wrap their ulcered feet in moleskin, wouldn’t have to forego handshakes. They could walk in a crowd undetected. We were the last ones who’d live apart. We were dying out. These days, we could go home if we wanted to. We could leave any day. No one would stop us. We stayed, because we preferred it here, in the home we’d made for ourselves. Once, Lena tried to refuse a story. It was a private story—just Lena and one of us in a third-floor room in the Home. We tried to tell her of the rainstorm that saved our house. Our first house, in Galveston. It was one week after we left for the Home. The neighbors found out where we’d gone. They learned we had the disease. They thought we might have left something behind in the carpet or the linens that was catching, so they plugged bottles of gasoline with rags and lit them and tossed them through the windows of the house where we’d lived. The corner of the sunroom caught first, one little gleam before the flame scampered mouselike along the floorboards. Our wife was inside, and she came awake beneath a flat layer of smoke, already coughing, and she—Lena stopped us there with a hand on our arm. I’m tired. Maybe in the morning, you can finish. But we were sunk deep in memory. We saw the flames reach the roof. We saw them jig down the beams. We saw our wife in the bed we’d shared, not moving, not leaping from the bed, not making for the door. She lay as if still sleeping, making up her mind. We saw the fire truck rolling reluctantly—no lights, no sirens—up the gravel road. We saw the sparks spit from the curtains, seeding small fires in the floor. We saw our wife rise—weary and annoyed, as she often was of a morning—and walk through the small flames that pitted the floor out into the yard, burning her left foot so badly the entire sole later peeled away in one piece. We looked up then, and we saw Lena scrunched in the hand-crank chair, rolling it a little forward, a little back, her eyes fixed on the window—not looking through it. Looking at the glass. We apologized to her. We held her and promised not to tell her those things again. Privately, we thought she should be stronger.

Many of them came to us for construction supplies. We sold the supplies at a discount, because it was clear they’d expected the check they were cut by the government to go further than it did. Laid a sewage line, and I’m broke. One painted a dove in flight on a glass window and traded it to us for three months of groceries. That window is still up in our chapel. Some came to us for loans. Some hired on construction workers from companies out of Florida and Tennessee. People who knew how to square a corner, how to brace a deck, took to sitting on the concrete walls around the Home on Monday mornings, waiting to get hired on for the week. They never came to us for advice, but we found ways to offer it. We printed the plans we’d drawn up for our houses, bound them and shelved them at our library for easy reference. They didn’t reference them. We told them as we scanned their groceries that they didn’t need to build on pilings. They built up anyway. Water’s always coming. You can’t hide from the water forever. One built a house with a domed roof. For wind protection. One built a house entirely of rubber tires. One walled off the bathroom in glass, so you could see them moving from toilet to tub, a dark curve. Lena’s father planned two bedrooms, which was what he could afford, though Lena begged for a room to herself. One planned a second-floor porch, then cut it to cut costs and now has just the door, swinging out onto nothing. One was struck in the head by a falling beam and died. One built the frame for the house they’d always wanted and ran out of money and hanged themself from the rafters. Their partner put the lot up for sale, buried a statue of St. Joseph head-down in the yard, and went south again. One built an exact replica of the house they’d had on the island, hung the same photos, drew a water line in blue pen on every wall. One dug for a basement like the ones in the Digest. They hit water, of course. Underneath, it’s just like the island, same goddamn water, same goddamn place. Most built beyond their means. We resented their extravagance. Our houses were two-room boxes of various colors, which we’d built ourselves from spare lumber and scrap metal. Few had a bathroom. Fewer still a kitchen. The doctors hadn’t wanted us cooking for ourselves. All our lives, we’d fried stolen eggs, used old license plates for pans. We could still be overcome by the intimacy of a saucepan brought to a private simmer. We thought them spoiled, entitled as children. Some of them built nothing, simply continued living in their FEMA trailers, their things piling up in the yard, and we disliked them most of all.

In the center of their plots, they wanted a replica of Easy Street, complete with facades for Stein’s Cleaners, the Jazz Café, the Fatty Shack, and a jetty extending out into the trees. They built just the jetty before they ran out of scrap wood and nails. Not even a full jetty—a stub of a jetty, resting on the grass. They sat out there dawn until dusk with coolers open and empty at their feet. They invited us to join them, but direct sun inflamed the disease. As we passed with our parasols, headed to the grocery or headed to the Home, we asked them, “What are you doing out there?” They said they were fishing. We talk. We laugh. We catch a catfish. But the boats they’d hauled up from the island sat on trailers in the corners of their lots, yellowing in the sun. In the evenings, they would stagger home beneath the weight of their tackle gear and ice. We put up a “Now Hiring” sign at the grocery, though we didn’t need more hands. They didn’t apply. In the privacy of the clinic yard, we began to call them lazy.

We gave them honey sticks. We gave them gumdrop tomatoes from our garden plots. We gave them two schoolrooms in the lowest floor of the Home, so they wouldn’t have to bus their kids into town. They taught classes in French and wasted Wednesday mornings on the Bible. We said nothing. We couldn’t give them everything they wanted. They wanted to use the tennis courts, but our knees were no good for tennis. For years we’d used the courts for shuffleboard. Some of them wanted their own church, named after an obscure saint, but there was only one priest willing to come out weekly from Baton Rouge and no sense building more houses of God than you had men to shake their fists in them. Some of them wanted to print their own newspaper on our presses, but we had an award-winning paper. We didn’t need another. We thought they understood this.

We didn’t choose favorites, though if we had we’d have chosen Lena. Lena, who was not quite one of them, not quite one of us, who walked from their jetty to our rose garden with such ease you could almost believe, watching her, there was no barrier between us but distance. When others tried to follow her, they found the garden deserted, the museum closed for lunch, our doors shut against them. If they caught us outside, they stammered a greeting and walked past, like they planned to stroll all the way to the city. They preferred to meet us on the neutral, ritualized grounds of the card tables or the shuffleboard court, where the rules were long-standing. Lena was different. Some said it was because of the age she was when they came here—old enough to know her own mind, but not so old it had gone rigid and brittle as dry clay. Some said it was her sister. They pointed out the day in the Coke bottle garden when Lena caught her reflection in the distorted glass of one bottle and spooked—her breathing too fast, her hands spidering over her face. When we asked her what was wrong, she said, I saw her. We understood she meant her sister. We saw figments, sometimes, in the long-unused rooms. We sometimes woke to the smell of link sausage browning in the Home’s kitchen, though the power was cut to that kitchen at the turn of the century. Maybe Lena understood us on account of losing her sister. Some said Lena was just one of those people oblivious to the niceties of others, as a ghost is oblivious to the distinction between doorway and wall. But Lena was never oblivious. You could tell by her smile, a sly mischievous smile, which she wore when she knelt in the garden beside us—a smile that said she knew she was getting away with something. She pressed her luck. She asked us for her own room in the Home, a place to escape her family and the ghost of her sister. We didn’t give her a room. Those rooms had their own ghosts and had to stay shut. Some of us still regret that. Some of us would have shared a room with her, if she’d been interested in sharing. One of us told Lena she loved her, a confession Lena received gracefully but with a certain formality, a distance that dissuaded further admissions of that kind. Some of us believe if we’d just given her a room, one room, everything would have come out differently.

When they forgot where they were, we reminded them. When Ricardo spun up off the coast of Senegal, crossed the Atlantic, ricocheted off the Yucatán, and swept up onto the delta, we reminded them they didn’t need to board their windows or tie down their patio chairs. They didn’t need to stock jugs of water and gasoline, buy extra cartridges for their guns. They didn’t need to invest in radios—hams and handhelds with antennas long as a grown man’s arm. “We’re a hundred miles north of the delta,” we reminded them. When they let the faucet run to fill their tubs, in case the lens of groundwater went salty, we reminded them we’re on county water. When a boy died of carbon monoxide poisoning from his family’s generator, they sent Lena to tell us. Same thing happened in Rita, she said. Happens every storm. We reminded Lena there was no storm. They hadn’t needed the generator. A boy died, Lena said. A boy died—don’t you care about that? But he hadn’t died here, we said. He hadn’t died in our Home. In our Home, kids didn’t die of generators or trains. Only on the island would you hear of a thing like that.

Lena looked at us then like she didn’t know us, like we couldn’t be trusted to tell a hurricane from a leaky faucet and couldn’t be trusted to give a damn. We’d seen that look before. We’d seen it on the faces of the state workers who came monthly to trim our hedges. We’d seen it on the faces of the ones who spent their days out on the jetty. We never expected to see it on Lena’s face.

We learned the funeral for the boy would be held in our chapel from a notice on the chapel door. We didn’t attend, unsure of our welcome, but we sent two platters of deli sandwiches and a king cake to be neighborly.

Somehow, we never expected them to get old. We never expected them to settle in. We never thought they’d get jobs with the National Guard or the state prison. Never thought they’d get degrees in finance and medicine. Never thought they’d want a quarter share in our grocery store or a voting position on the Friends of the Library board. Never thought they’d get the hip surgery they’d been putting off or sell the boats sun-bleached from years out of water. We never thought Lena would get an assistant realtor job in Baton Rouge, would get insurance to cover the hormones she needed. We never thought she’d be the one to sell the Home, our Home, but she was—sold it for the state, for a 10 percent commission. Lena sold it fast to Sunset Living, the first company that placed a bid. Sunset Living planned to turn it into an assisted-living center for folks from New Orleans. We never expected the lights to flicker on again in the upstairs windows of the Home, but Sunset Living started to renovate. Sunset Living offered us rooms at a discount. They offered to make sure we were comfortable right up until our end. They sent Lena to talk us into it. Lena wanted us to stay. Lena tried to tell us she’d been thinking of us when she sold the Home, tried to tell us the change was what we needed. Lena talked fast and smooth as any salesperson, had the shine of someone who’d found a place for herself. We refused to stay. We would not live again in the too-warm rooms where doctors could enter without knocking whenever they liked. We would not die there. We left. In cars driven by nephews and third cousins. In a coach-class seat on the Amtrak Sunset. On planes bound for Incheon and Philadelphia. After we left, they sold the gauze masks and the bike chain chair. They sold the photograph prints of the front corridor for ten dollars apiece on eBay. They sold tours of the Coke bottle garden. They sold our houses. They disinfected them with medical-grade bleach, stripped the carpets and the wallpaper. They sold them as Craftsmans, which they were—every board sawed, every nail pounded, every screw drilled by hand. Once, Lena called us to tell us about the renovations of our homes. We didn’t pick up. Lena talked in the message about dormer windows with pillowed seats and frescoed mantels. We recall how she sounded in that message—with a note in her voice like she needed our approval. We called her back, left our own message—You’ve done real well for yourself, we said. We imagine Lena replays that message in front of the mirror in her Craftsman home. Sometimes, Lena hears our voice. Sometimes, the voice of her sister. Sometimes, she burns her hair with her straightening iron, and the smell reminds her, for no reason she understands, of us.

This we know to be true: When there’s a storm, they tune in to the Weather Channel. They sit before the television. They watch their old home go under, up to its neck in lapping waves. They do not think of us, but as the drones pan over their old island, they bite their cuticles and look for their houses. They say, Baby, be there, which we taught them to say. And as we, in doctor’s offices in northern cities and countries across the ocean, look at X-rays of dark fluid seeping into our weary, porous lungs, we use their words for acceptance—You can’t hide from the water forever.