Mason did not speak the entire ride home. He sat instead staring out the window, arms folded across his chest. It was the middle of the day, and there was little traffic. In the driver’s seat, Howard, his father, read aloud every sign they passed, hoping to elicit a response. “Mystic,” he said. “What a name. Makes you think it’s some sort of Brigadoon, right here in goddamn Connecticut.”

Mason remained silent, tugging down one side of his hoodie’s drawstrings then the other, until the fabric clinched his neck. The word “thrasher” was printed across his chest in flaming orange letters. He rolled down the window and craned his body out. The December air was bracing and smelled of coal. Piles of slush leftover from the previous week’s snow hemmed the road.

“Nauseous?” Howard asked.

No response. Howard turned down the heat anyway.

Disciplinary probation was the term Dean Matthews had used on the phone earlier that morning. What Howard needed to understand, Matthews said, was that the school had come under scrutiny for their prior rulings in such cases.

“Let’s call a spade a spade,” Howard interrupted. “You want to pillory my son for the sake of some institutional bullshit.”

Matthews was quiet a moment. Howard tried to picture the office a man like Matthews might have: nondescript oak furniture, microfiber chairs, a set of mullioned windows overlooking the campus quadrangle—dignified, if fusty. He tried to picture the man himself, too. A man with a cheery face that bore no hint of awareness of his profession’s encroaching obsolescence. The internet had won out. Everything was going online these days, even higher learning. The thought made Howard feel superior to Matthews, who at last said, “It’s a good thing the girl didn’t file charges with the police, Mr. Kidd.”

Howard had received the call between his second and third cups of coffee. He was supposed to be using this time to search for a job—Mason had even texted him his login to the university career portal for precisely this purpose—but he couldn’t muster the motivation. Most mornings he spent watching treacly talk shows, or occasionally jerking off. When he reached for the phone, he expected to hear his addled father-in-law on the other end, mumbling about some upcoming golf trip whose existence his home aide had denied. Instead, he was greeted by the politic voice of Mason’s college dean, saying that the committee on sexual assault had found Mason guilty and was putting him on probation. What committee? Howard asked, his volume rising despite the pill he took daily to inhibit his temper. Dean Matthews cleared his throat, embarrassed. Let’s start again, he said. There had been some trouble a few months ago, involving an allegation raised by one of Mason’s female classmates. Matthews was sorry to be the bearer of this news; he assumed Howard knew.

After obtaining what few facts he could (confidentiality barring the rest), Howard phoned Noelle at the law firm. Her secretary answered. Noelle was in a meeting with a client; would he care to leave a message? Howard recognized this business with Mason was an emergency, and that he ought to say so. But he was stymied by a vision of his wife racing out of the conference room, only to have her dread morph into displeasure when he relayed what had happened. “Can’t you take care of this?” she’d ask, in a metallic tone that implied he couldn’t.

So Howard told the secretary a message would do just fine, though he sensed Noelle wouldn’t call. She would see his name, scrawled on a Post-it note, and decide whatever it was could wait.

At forty, Noelle was the rare litigator who’d never even contemplated going in-house; so enamored was she with the trial process, the taking of depositions, the crafting of a winning opening statement. To no surprise, she won every argument that transpired between her and Howard; a single perturbed glance could reduce him to stutters. Like the time he accused her of caring more about her clients than him, and she rose from the bed and shouted that the only reason she logged so many hours at the office was because someone needed to provide for their family. It was a cruel, low blow. And Howard felt, for the first time in their marriage, a desire to slap his wife across the face.

His last layoff had come only a month ago. Noelle hadn’t taken it as harshly as Howard himself had. She said it was a good thing, that now he would have time to figure out what it was he truly wanted to do. She viewed his job at the sports streaming site as little more than a pet project, a tangled yarn for him to paw at while she raked in the real money.

Neglecting to signal, Howard turned onto their block. Their neighborhood was a relatively small one, where each street was named for a British county: Somerset, Devon, Essex. “Slow Down for Children” signs spangled the wide lawns. Nearby, the Long Island Sound nourished the marshy sedges that girded the coastline.

“Did you speak to Mom?” Mason asked.

Howard shook his head. Then, startled, said, “Did you?”

Mason nodded. “She’ll be home late.”

Howard wondered what the boy had told his mother. Had he hinted anything to her over the past few months when the investigation was taking place? Mason and Noelle were closer to each other than Howard was to either of them. During dinner, Noelle’s phone would sometimes buzz, and she would rush to pick it up, breaching the sole house rule she’d once upheld as law: no phones at the table. It was how the Buddhists ate, she said: mindfully. After she hung up, Howard would ask how Mason was doing, and Noelle would studiously peer into her risotto, offering some cursory response that ensured Howard remained on the periphery of their interaction.

After several attempts with the garage clicker, the door finally yawned open.

. “Can you get out and move those bins?” Howard asked.

“What bins?”

He pointed. The Public Works Department had recently sent the town residents new recycling carts. The carts were mammoth, practically a dirigible side by side; large enough to hold a hundred gallons each. Every time Howard pulled into the garage, he needed to shift the bins to keep from scratching the side of his car. He’d complained about this inconvenience to the town council, going so far as to attend one of their open meetings. This was the new way, the councilman replied unyieldingly. From now on, a truck with an automated arm would come around biweekly to retrieve waste, reducing the necessary manual labor from three sanitation workers to one. Ah, yes—the great Carousel of Progress.

Mason stayed outside while Howard parked. There was something imperceptibly different about the boy, though what, Howard wasn’t sure.

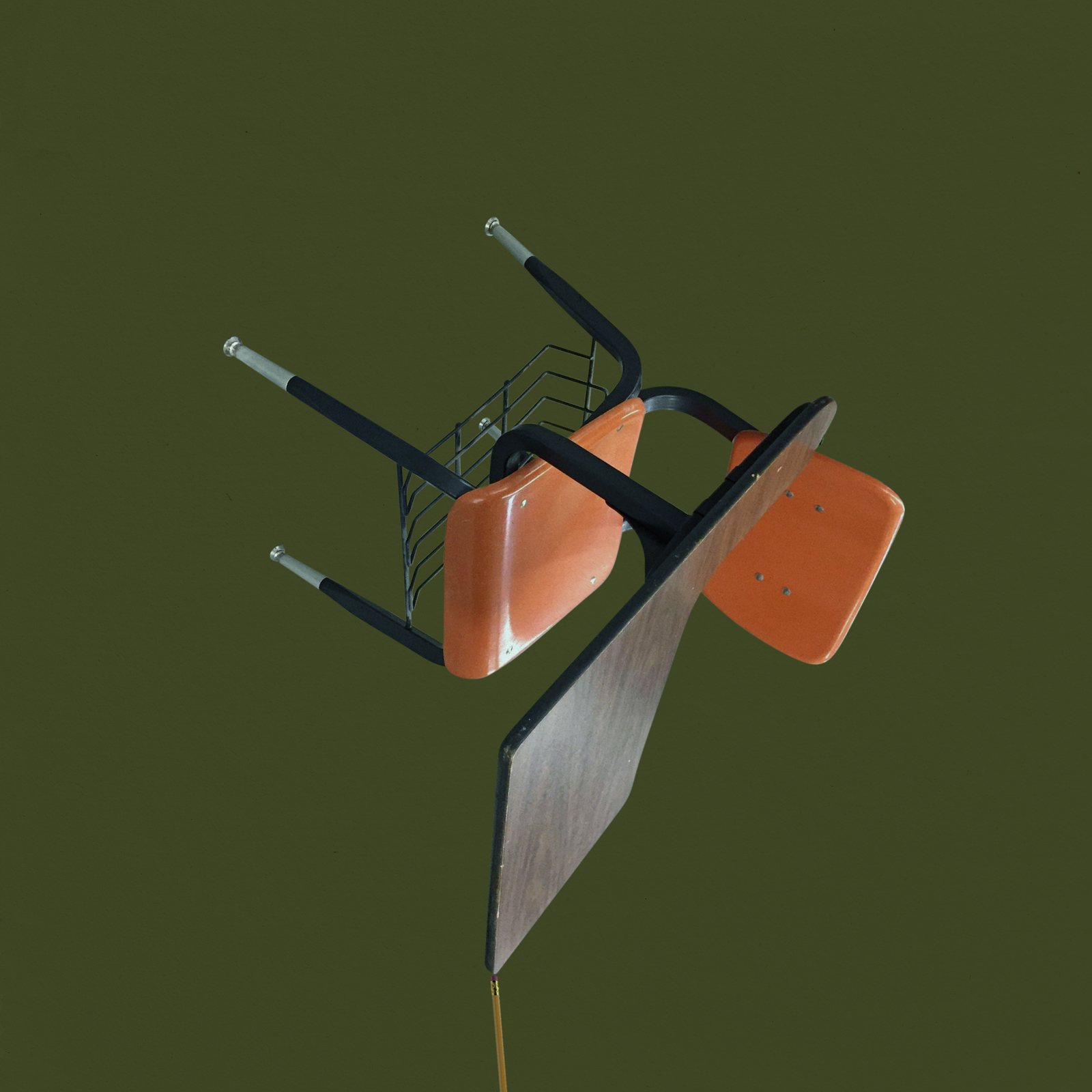

He cut the engine. From the doorway, Mason called that he’d help unload in a minute. Howard cast a glance to the backseat, where boxes were piled so high they obscured the rear windshield. The car looked as it had two years prior, when Howard and Noelle moved Mason into his freshman dormitory. Every day that summer, before departing for work, Noelle had penned a list of objects they still needed to purchase for the drop-off: extra razor blades, more socks, plastic drawers. Howard tried to make the frequent trips to Target into a bonding experience, but Mason always had somewhere else to be—the mall, a pool party, hanging out in Lindsay Fogherty’s basement. Howard suspected Mason was distancing himself, steeling his heart against the impending pain of farewell. But such understanding didn’t make his son’s withdrawal sting any less.

In a meager display of helpfulness, Howard lugged Mason’s duffel inside, past the mirror where Noelle liked to check her make-up, past the framed art projects from when Mason was in grade school, before he’d forsaken such creative passions for soccer. He had played center midfield on the varsity team. For a while, it looked as though he might have a future in the sport, or at least be good enough to be recruited by a Division I team. But in the spring of junior year, he broke his foot. What Mason had felt, sitting in that orthopedist’s office, was not despair, not insofar as Howard could surmise, but something closer to annoyance. At no point did he seem to think: My athletic career is over. This, however, is what Howard thought, because he’d seen players’ prospects crippled by lesser injuries. In the time Mason was forced to sit out, others would improve to take his spot. That Mason did not regard this setback as the terminus of his short life’s accomplishments evinced in him a cloistered idealism which Howard both envied and pitied. He wondered now if the change in Mason—the surly exasperation that flashed behind his eyes—had occurred then, in the instant his bone revealed itself to be cracked. And had it occurred slowly, a progressive corrosion, or all at once?

The previous June, the shocking totality of this change emerged when Howard received a phone call from the police, saying he needed to come pick up his son. Plunged into darkness, the neighborhood streets seemed sinister and strange as Howard wound through them, driving as fast as his nerves would allow. It wasn’t like Mason to get caught sneaking into an abandoned house to take ecstasy with his friends. The Mason he knew still enjoyed Saturday morning cartoons and cowered at the sight of a spider. Howard pulled up behind the police cruiser, whose brash lights stained the sidewalk red. Conscious of the officer’s eyes on him, he advanced hesitantly, stopping when he and Mason were still an arm’s length away. Mason recoiled, and though this manifested only in the shudder of his shoulders, Howard sensed a larger part of the boy folding in on itself.

“I guess the answer is yes,” Mason said, smirking.

“What?”

“You used to ask me: if my friends were jumping off a bridge, would I jump, too?”

In the kitchen, Mason opened the pantry. He frowned as he considered the options. “Rabbit food?” he asked, gesturing to the stacked boxes of Fiber One and Raisin Bran.

“Mom’s on a health kick.”

After a few seconds of deliberation, Mason reached for an unopened jar of peanut butter and a loaf of Ezekiel bread. His complexion, the same as Noelle’s, was pale beneath his dark hair. On one cheek shone a patch of scabbed skin where he’d picked a zit. He appeared to his father somehow dimensionless, like one of those cardboard cutouts of sports players he used to beg for every Christmas.

“Well,” Howard said. “Welcome home.”

Mason replied with a veiled, courteous smile, as he might extend to a friend’s parents. From the center pocket of his hoodie, his cell phone materialized. He tapped at the screen, swiftly immersed.

Beyond the porch door, contrails abraded the sky. Crude chalk drawings of reindeer galloped across the neighbors’ drive, drawings that had not been there yesterday and would not be there tomorrow, after the rain. In small ways, Howard managed to keep track of the world. Two young boys lived in that house, each with his own shiny bicycle. The bicycles were outfitted with bells that the boys would ding when they zipped down the street. Noelle loved that, how suburban it was. Howard never told her about the time he saw one brother shove the other into oncoming traffic. There was a beastly, Cainitic spirit in those boys that he did not trust.

The phone rang. He grabbed for it, grateful for something to do. “Hello?”

“Is this Mason Kidd?” a girl asked. Her voice was high-pitched, a register that belonged to the young. Howard thought he heard other girls, shushing each other.

“Who is this?” he asked.

“Fucking rapist. We stand with survivors and will not be silenced.”

Howard slammed the phone down, as if it were a wire that had suddenly gone live in his hands. Inside his chest, his heart wheeled, a globe spun too quickly on its axis. He glanced out the window, expecting to find a horde of paparazzi huddled in the bushes. Instead all he saw was the cold sun, unscrolling in urinous rectangles over the snow-covered grass. Next door, workers were felling a tree.

“Spam call?” Mason asked. His features were untroubled, and Howard had a vision of the two of them back in the doctor’s office, with Mason’s swollen foot propped up on the table. Was it possible the severity of this latest indiscretion had also failed to reach him? Anger ballooned behind Howard’s stomach, and he dragged his attention to the table to calm his raging pulse.

Three of Noelle’s pens were lined up on the table’s edge, which she used as a writing desk, because she liked the light through the kitchen window best. Her denim jacket, decades old but recently deemed worthy of saving, remained hung across the back of her chair. A few weeks ago she’d gone on a spree, purging her closet of items that ceased to bring her joy. She’d gone so far as to transport the jacket to the Goodwill in Westport, but when the cashier asked if she planned to donate it, she said no and walked back to the car with it slung over one shoulder.

Mason sat hunched forward, elbows on knees, as if on gym bleachers. The seat cushion beneath him was fraying; it needed to be reupholstered. Howard supposed that was his job now, too. What a humdrum existence he had stumbled into, a crater that proved to have no bottom. “You can do anything you want,” Noelle had said on the day he was laid off, her eyes roaming the contents of his office, packed tidily into a single box.

“Can I borrow the car?” Mason asked.

Howard studied his son’s face, the one he knew so well. There was an inborn quality of entitlement in that face, a moneyed composite of lineaments that Mason had inherited from his mother. This was the same boy Howard had picked up from sleepaway camp three weeks early because he wasn’t having a good time; the same boy who’d fretted the Tooth Fairy wouldn’t be able to find him if he lost his tooth while staying over at his grandparents’; the one who spent hours on the lawn, disturbing anthills with a stick. Yet this was also the boy whose name had been printed on the truancy letters that arrived in the mail senior year; the one whose report card came blackened with subpar marks. Had they been too lenient? Howard remembered the condom wrapper he discovered in Mason’s pocket while doing laundry. The wrapper struck him as a mockery; how ineffectual his and Noelle’s order of no girls in the bedroom seemed when met by a teenager’s hormonal defiance. Yes, Mason was different, and confirming this, Howard became aware of how little he himself had changed.

Last May, to celebrate their twentieth wedding anniversary, Noelle had thrown a backyard party, complete with a canopy tent and caterers attired in black and white. Over hors d’oeuvres, dozens of friends approached Howard to extend their congratulations. What a major accomplishment it was, they said. A major accomplishment what was? he wondered. But he’d felt, too, infused with pride. Mason had already been accepted to college; Noelle had recently made senior partner. Perhaps these successes indicated Howard had done something right, even if he wasn’t the obvious beneficiary of his actions.

He pulled out the seat across from Mason. “So. Should we talk about it?”

“What is there to talk about.”

“Did you do it?”

“Jesus.” Mason stood, tugging down the hem of his sweatshirt. He was so tall, his head nearly grazed the hanging light fixture. “How could you even ask me that?”

Mason slammed his hand against the back of his chair. The feet screeched over the tile. Howard glanced down to see if they’d left a mark.

The phone rang again. This time, the ring sounded shriller, more menacing. Howard considered letting the answering machine pick up but was terrified of those girls, the message they might leave. “Hello?” he answered.

An older man’s voice: “Noelle?”

“Oh, hi, Dad.”

“Hi,” Bill said. Then, after a pause, “Who’s this?”

“It’s your son-in-law, Howie.”

“Howie,” Bill repeated, without recognition.

In recent months, Bill’s cognition had plummeted. On the worst days, he had accidents while shuffling to the bathroom. He forgot how to properly sit in a car and would crawl into the passenger seat on all fours. He recited the same few sentences on a loop: “Did you hear PBS is showing Carousel tomorrow? I always liked that musical, especially that one song—how’d it go? On the subject of musicals, did you hear PBS…” Noelle couldn’t stand this. After her father parroted the same statement three times in a row, she’d snap, “We already talked about that.”

“Listen, Dad,” Howard said, “I’m in the middle of something here. Can I call you back in a few?”

“Oh, sure, sure,” Bill said, the words frayed. He was crying.

Howard’s heart started that uncomfortable wheeling again. “What’s the matter?”

“It’s nothing.” Bill inhaled, a choked sound, the air wrestling to maneuver past the obstacle course of tears in his throat. “It just feels like everything’s caving in.”

“Ain’t that the truth.”

Across the kitchen, Mason retrieved his duffel. Howard watched, wondering what it was that separated the happy from the un-. He used to believe it was money—that wealth alone formed the invisible moat—but then he married Noelle and discovered money was not the source at all.

On the end of the line, Bill cleared his throat, forgetfulness reasserting itself to both their benefit. Yesterday, he’d been in Florida, he said. What paradise! By God, those palms—wasn’t Florida just the loveliest place to be?

*

In the bathroom that evening, Howard stared at his reflection while the tap ran. When Noelle was near, he often ran the tap, to make her think he was washing his hands. Their marriage was filled with little performances like this.

She knocked.

“Come in,” he said, turning off the water.

Noelle entered in her work clothes: low black pumps, a silk shirt, a tweed pencil skirt that drew attention to her long legs. Model’s legs, Howard called them. “I bet you’ll win cases with those legs alone,” he used to say. Her hair was clamped by a tortoiseshell barrette, her nails painted an innocuous pink. Her office had relaxed the dress code several years back, but she still maintained an aspect of presentability, regarding with disdain the interns who arrived in short-sleeved shirts from Uniqlo and H&M. Howard wondered if she was having an affair with someone from the firm. Her blouses were cut lower now than they used to be, her skirts higher. An ambience of newfound confidence surrounded her like a shaft of sunlight.

It had been months since they’d last slept together. Noelle claimed she no longer enjoyed sex. Worse, it was suddenly painful to her. Howard tried going slower, faster, more foreplay. Each time, Noelle would make small noises that could not be mistaken for ones of pleasure. When this happened, Howard shut his eyes and pictured another woman beneath him, one he’d passed on the street, or in the supermarket, or had merely glimpsed on TV. Sometimes it was Noelle herself he pictured, a younger version of her, the one for whom he’d fallen twenty years before. Once, during one of her whimpering fits, he gripped her by the chin and said, “Look at me, goddammit.” At the memory, he shivered. The net of culpability had already begun to weave its constricting fibers around him.

Oh, how he despised that girl, the one causing everything in his life to spoil. What was her name—Sydney? Alyssa? What did she look like? Had he passed her on the quadrangle, at move-in day? No doubt her parents would champion her through this. It was easy for a parent to show support when their child was not the accused.

The phone rang. Howard and Noelle stiffened, a silent negotiation passing between them. All evening, the calls had been coming, their ringing filling the house like gathering smoke, the girls’ hateful words spewing fire across the line. At one point Noelle picked up, planning to yell at whoever was there, but she heard only heavy breathing. Livid, she lobbed curses into the receiver, until Howard eventually pried the phone from her shaking hands.

The ringing cut out. Noelle broke the stillness first. She uncapped her lotion and smeared it over her elbows, rubbing the excess into her neck with a practiced padding motion, as if kneading dough. After a while she said, “Did you speak to him?”

“And say what?”

In the mirror, she frowned. “Anything. That we’re on his side. You told him that at least, right?”

Howard had not said this. Hadn’t his support been implied by his willingness to drive the 150 miles from Connecticut to Boston back and forth?

“You knew about this, didn’t you,” he said.

Noelle’s eyes stayed pinned on her own reflection. A streak of lotion like a comet’s tail glistened beneath her chin. When she spoke, her jaw remained rigid, the words flattened between the vise of her teeth. “We’re going to sue the university for defamation of character, and any other charges I can tack on. I’ve already drafted the paperwork. The report said the girl was drunk. Do you have any idea how that will play in court? A private institution like this, they’ll want to settle just to avoid the bad publicity.”

“But you knew,” Howard pressed. He saw himself in the laundry room, the condom wrapper between his hands; his comprehension swerving to calculate how much he’d missed, and when.

“He’s our son, Howard. I’ll do whatever it takes to protect him, and so will you.”

They finished their evening routines in silence and retired to the bedroom. Howard went to draw the curtains, squinting into the darkness to make sure no one was lurking nearby. How long before their address surfaced online? The paranoia was too much. He fought the urge to corral Noelle and Mason into the SUV, flee far from this house.

Off the snow, the moon glinted like a searchlight. The bushes huddled, their forms faint and threatening. In summer, Noelle paid people to spray the leaves so the deer wouldn’t eat them. The deer came anyway. They reclined on the lawn, immobile as haystacks. Howard wondered if their fawns would develop mutations from all the pesticides. He tried to feel guilty for this but experienced only a dull rush of anger at the deer’s stupidity.

Noelle reached for the remote. The television pixelated with an image of a home’s lavish interior. The rooms were neat, the furniture curated to match, as it only ever did in the aspirational world of Hollywood. On opposite sides of a kitchen island, a couple went about their tasks. The woman was making macaroni. Sighing, she dumped the pasta into a strainer, steam rising to obscure her face. The man—her boyfriend—was trying to prompt her, asking what was wrong. She responded coolly; nothing productive would come of this conversation, she said.

“Is this how every couple fights?” Howard asked, laughing in jumpy recognition.

Noelle didn’t look away from the screen. “What, did you think we were unique?”

“No. I just thought there was more variation.”

How demoralizing, that even his arguments with Noelle, which appeared so particular, could not distinguish him from other men. What else did he have going for him, really? He was past the age for ambitions; everything now was about acceptance, making peace with one’s fortunes. To want more at this stage seemed inane, like waiting for a train long after its scheduled arrival had passed.

He diagnosed himself with lack of cohesive vision, purpose. Constancy bred success—that’s what Bill used to say. You put your money in the stock market one day, and eventually you would find yourself with a small trove. Forget trying to game the system. The Noelles of the world knew better than to waver. The only derailment to Noelle’s minutely planned future, in fact, had been her pregnancy with Mason. She and Howard, high school sweethearts bonded as much by comfort as by any love they felt for each other, had been dating two years when they found out. Noelle wept as she told her parents the news.

To their credit, Bill and Edie received their daughter’s announcement warmly. They celebrated with takeout and a game of Trivial Pursuit. Howard sat by sulkily as Noelle leapt to answer questions about Rembrandt and which state housed the Baseball Hall of Fame. “I hate that game,” he said on the drive home. “It doesn’t even require strategy; it’s just about reciting stupid facts.”

“Okay,” she answered tightly. “We won’t play it again.”

Howard knew he was overreacting but couldn’t stop himself. Deep down, he felt Noelle had chosen the game to humiliate him, to prove he wasn’t as worldly nor as knowledgeable as she; that her being with him was a kind of settling.

On the television, the couple’s argument fizzled into passive-aggressive looks fired across the bedroom. Soft jazz music played as the woman climbed into bed, angling away from her boyfriend. Noelle did that too, Howard thought. Closed herself off. She had done it now without his notice, fallen asleep with one hand clutching the remote, her nose hugged by an anti-snoring strip.

He peeled back the duvet and tiptoed out of the room, down the stairs. He did this when he couldn’t sleep, fashioned a bed on the sofa using the cable-knit throw. Noelle never commented on it when she left for work in the morning.

The living room was dark save for the hazy light from the entertainment center, where a QVC infomercial played mutely. For a few seconds Howard believed he was alone, until Mason’s phone flashed on the coffee table with an incoming alert. On the couch, Mason lay with one hand on his forehead like a fevered patient. He rolled over and tapped the phone, then turned away again, sanding his palms along his pajama bottoms to dispel what he’d read.

“You scared me,” Howard said, moving in closer. Around him, the air took on a granular quality. There must be something beneath it all, he thought.

The phone screen illuminated again, and Howard saw that Mason had been crying. “What am I going to do?” Mason asked.

“We’ll have to figure it out.”

“And if we can’t?”

The ceiling beams above them loosed an ancient sigh. Howard imagined Noelle awaking, her hair rumpled, her Chicago Bulls nightshirt twisted. It was a mental snapshot he’d once taken of her. He had other images like this too, preserved in the amber of his mind. It was never the ones he expected. Instead, his memory was crammed with insignificant scenes: the anthill on the lawn collapsing when prodded; the neighbors’ boys carving at the night with Fourth of July sparklers; Mason, age three, wailing after Howard tucked his thumb between his second and third fingers and teased, “I’ve got your nose”; and Noelle, later, calling this gesture cruel: “You’re his father. It’s no wonder he believes you.”

He believes you. The words echoed in Howard’s head.

“It will work out,” he said feebly.

“You don’t know that, though. You can’t say for sure.”

“You’re right, I can’t.”

He felt embarrassed by his own inadequacy. If only he could call Bill, his erstwhile conduit to the fatherly wisdom that flowed just out of reach. The poor old man. How easily Howard could envisage his funeral, months or even weeks from now. Noelle would remain composed through her eulogy, but the toll of the past year—the lawsuit she planned to file against the university, the nightly phone calls bearing increasingly specific threats, Mason spending all day in bed cycling through the same few violent video games—would be visible in the bags beneath her eyes. Visible in the diminished crowd of guests paying their respects.

Howard rocked his jaw side to side, dislodging the tension settled there.

On the couch, Mason fidgeted with the remote. He let out a breath, unlocking the sob he’d been holding back. “I fucked up big time, Dad.”

Howard opened his mouth, praying for words he did not have to coalesce in the space between them. Resigned, Mason set his head on a round accent pillow. Howard watched, thinking of that other father—the girl’s father—caring for his own child tonight. He unfolded the throw and draped it over Mason as softly as he could. Tomorrow. Tomorrow he’d tell Mason to get a job, start applying to transfer schools. Exhausted, he sat down beside his son on the sofa. They clung to each other like two passengers emerging from a shipwreck. Howard pushed back the boy’s hair. Just as he was about to speak, the phone rang.