A very thin, curved man was yelling at her. He was yelling at her to wake up! She had no reason to wake up, she had no tasks that needed to be done. They had been over this, day after day. He did not understand that a person needed a reason. He had a reason, that was the irony. He was driven by reason, by entire situations, his whole life was a series of arrows, and you could see by the way he had shaped his body like an arrow too that he very much understood, in some primal way, that people need direction. But out of her words, out of the things she merely said, he could not grasp a thing. It’s the morning! he said. And she would explain that she knew that, that this happened every day, but it did not change the fact that there was nowhere to go from here. To this he would simply fling back the curtains.

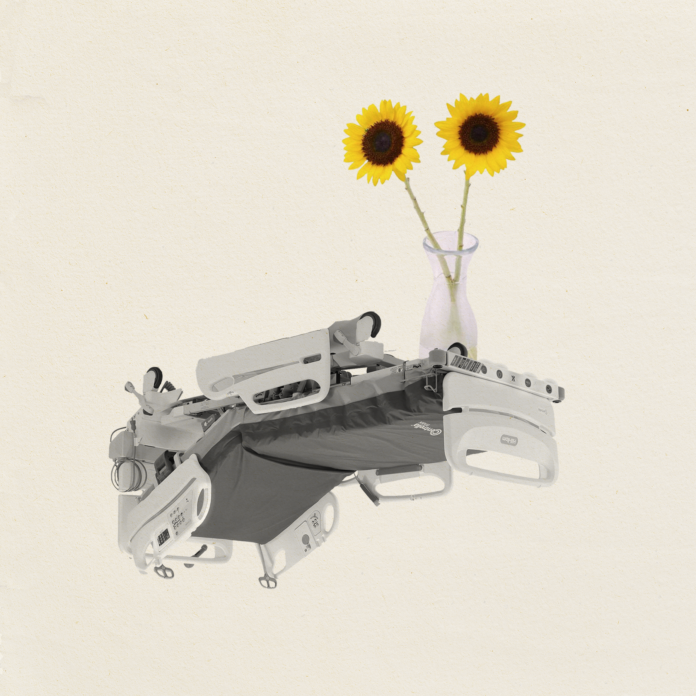

He flung. He flung constantly. He flung juice at her, he flung food at her. He flung pills at her and demanded she take them with bravado. He wanted to get the very best out of her death. He did not seem to accept that that’s all she was doing, just dying. He wanted her last breaths to be strong, full of power and emotion. He wanted her final glances to draw a person in, show them everything she’d ever seen. He did not understand that she was only waiting, that there was nothing else to do but wait. He thought if they worked together, if they gave it their all, her death could be the best one this town had ever seen.

Some weeks after he had taken charge of her she heard, from another dying person, that he had not been doing this for long. He was so moved by his own mother’s death, it turned out, that he had stopped everything he was doing and gone to nursing school. He did have a family, he had a wife and two daughters, he had told her this, and she did not understand how a person of his age and stature could have the time and energy to do this sort of thing, but apparently his mother’s death had been beautiful, perfectly executed, well received by everyone who had taken part. To create more beautiful deaths became his sole passion. He had been, before this, a chamber music director, a PhD in fact. His name before he became a nurse was Dr. Richmond. He was not a doctor here, not even close. And he never claimed to be one either. He was Nurse Paul. She hated him so much.

She wanted to die immediately, of course. That was true before she’d met Paul. But now she wanted to die horribly. She wanted to die in such a way that he would understand that there was nothing beautiful not only about death but about life too. When she ate she tried to take large, forceful bites, hoping to sputter out crumbs in her last gasps of air, choking on green beans served in plastic bowls. He wanted her to dance her daily exercises and she would not, she would stomp them, hit her leg down as hard as she could, which was never very hard at all. She hoped to break something, to fall to the ground and split in half. She hoped he would be holding her elbow when she collapsed, that it would pry itself off like it was already dust.

He did not seem to care that she wanted to crumble into several piles of limbs and skin right as he changed her sheets and nightgown. He rolled her over with a great strength that no man of his stringiness should be expected to have, delicately landing her on her other side, announcing that as always this would only take a moment, let’s just think of our very favorite things while we do it, let’s visualize the best party we ever went to! And with that he would wait, expectantly, like she might have something to add, like face-down in a cot where hundreds before her had rotted was the sort of place one could recall a thing that wasn’t death. When he rolled her back around she stared at him like he had dug into her ribs and rearranged her heart, placed it closer to the rest of her intestines as if he were arranging a plate. He wanted to eat her, she knew this now. He wanted to consume her insides, to taste every part of her, to feel in himself whatever inside her was worth something.

When you taught, she said, did you ever teach anyone good? And he laughed harder and shorter than she’d ever heard a laugh, a shout of a laugh that rang out and bounced off the windows that could not open.

He had sent, he told her, so many students to something much greater. He had pulled things out of them.

He had grabbed their voices out of their throats and strangled them until they understood how to work them. He was very good, he acknowledged. He was very, very good.

That night she wrote him a note. Dr. Richmond, it said, I do not have any talent. I do not have any wishes either. I do not have anything you can harness. I have only my death, and my death is my own. I do not want my death to be made into anything other than what it already is. I am happier this way. Not every person was made for greatness. We should die, I think, the way we lived. I want to die in peace. I want you to leave me alone.

She left it on the metal tray that moved towards and away from her, depending on what she needed. She slept not unpeacefully, but certainly not with any great calm.

In the morning he was gone. In his place was a woman named Eva. She opened the curtains without any gusto, she placed her pills down next to her and waited patiently for her swallow. She let her step out of bed slowly, move across the room without any sort of energy at all. She let her be blank. She was blank for her.

When she died Eva cleared off her desk, settled greeting cards into a pile and placed them in a paper bag. Her daughter arrived several hours after her final breath. She wanted to know how it had gone, she wanted to know how her mother had died. Eva did not really know. She held the daughter’s hand in hers and said probably it was very peaceful. Probably she felt nothing at all.