There were four tall men sent to complete the reappraisal. One of them, Devin, was the lawyer—we’d met before, five years ago, at the last estate meeting. Then there was Jeremy, Trevor, and Niko. Each had a skill: carbon dating, valuation, and damage assessment. Together they composed the team that would determine Charlene’s total worth.

The sun was barely visible over the hills when the team arrived. It was September and so warm that by midday oil evaporated from the driveway’s asphalt, forming small, rippling rainbows in the air. Charlene lived on one side of Los Angeles, toward the west where the freeway comes through the hills. The area used to be California middle-class, a place for people who believed in communal living and making cereal by yourself. It was mainly houses like hers now: multilevel, multimillion-dollar properties built into the mountainside. Each morning I went outside to observe the traffic. The horns below echoed through the canyon, its own sharp little music. Charlene and Robert’s house was above all the bad parts of the city, namely the smog, which sometimes coated the surroundings so well that I couldn’t make anything out through it.

Devin said he’d never been up this high, the air so blue you could see the ocean in it.

In fact, he said, I don’t think I’ve ever been this close to the sky.

Some people—apparently people like Devin—spent their days in the streets of the flatlands, catching only faint glimpses of the far beyond.

Wow, Niko and Jeremy and Trevor said, looking at the view.

I ushered them inside. On the other side of the canyon, I could make out the white curves of the museum and library where I’d spent a portion of my graduate studies. Its buildings were smooth, modern: they molded themselves to the hillside, their architecture the subject of numerous monographs. I’d applied to a position—Librarian III—in my final semester, only to be rejected without an interview. Like most classically trained archivists, I wanted, initially, a position at one of the major institutions: universities, museums, national databases. But the reality of it was that we were stuffed to the gills with library science students. Conservationists, archivists, whatever. Most of us fell into worlds like mine. The fear of unemployment was enough to keep us chained to people like Robert, ones who made the smart choice to invest in stable careers early on. We organized the possessions of the noble class, shelving their libraries and setting up data infrastructure.

Robert left his entire collection to Charlene when he passed on. It was a real whale of a collection. When I got the job as Robert’s new archivist, it was a small honor, out of the norm for someone with my background. I grew up in elementary schools built from groups of mobile trailers. My public libraries were small storefronts, their windows covered with metal grates.

Devin whistled as we entered the foyer.

Stained glass, he said, looking up at the ceiling.

Right this way, I said. We’ll start in the east wing.

Devin consulted the small binder I’d given each appraiser.

Barcarts and revolvers? He asked.

Ceramics, I said. Page nine.

Robert had obscure taste. The bulk of the collection belonged to an ambiguous category, Western frontier paraphernalia, made up of things like saloon decor and fur traps and ornate, embroidered bridles. He acquired a great number of old whiskey advertisements, mostly featuring nude women. Robert never met a riding crop he didn’t like. The collection of animal traps, principally from the Gold Rush era, comprised a large portion of the collection. This array in particular garnered attention from museums and colleges: I’d prepared several for exhibition over the years, packing them up carefully and shipping them to various locations across the country. His sharp curatorial impulse was one of the reasons why I remained at the house for so long. Back then my arms were no match for Robert’s wire snares. I spent many of my first days lifting boxes of them over my head, attempting to grasp the breadth and depth of his collection.

He converted one of the stagecoaches into a bed when I first moved into the basement apartment. My days were long, and it was easier that way, better than the couch in the screening room I’d fallen asleep on more than once. The stagecoach was one of the larger trolleys, big enough to fit a twin mattress and a shelf to keep my books and phone on. Robert made a window in the top of it, one I could see the ceiling through. He cut it out with his hands and an electric saw because he was practical like that, the type of man who could make skylights out of stagecoaches. I enjoyed the fact that I slept inside his collection. I updated its location in the database Robert and I developed, noting the alterations Robert had made to its composition.

- Stagecoach (Wyoming, USA, 1855): 1.

I soothed myself with the unruly parts of the collection. Robert’s interests gave me the opportunity to devise a categorical system. We created a database from scratch; I used the software I’d worked with in school and went from there, developing an information strategy that answered Robert’s needs.

We moved slowly. The ceramics collection was small, but valuable. Over the course of his lifetime, Robert amassed a few shards of Grecian pottery. I’d never seen any of it in the flesh before I arrived at Robert’s collection. Items like his—the shards, for example—were extremely rare. Most institutions sucked them up and spit them out, laden with wall text and shuttered behind bulletproof glass. To see them like this, raw, was an enormous privilege.

Jeremy insisted on dating the pottery once, then twice, then a third time. On the fourth go around, I turned to him, his face haggard and gray in the pale light of the tracing table.

They’re authentic, I told him. From a 2015 expedition near the Apennines.

He said nothing, bending over the scraps. Appraisers were like that. Tough.

By noon we’d only made it through the single-action revolvers. The Tiffany-handled Colts were next, and they would take a considerable amount of time to appraise: the silver was varnished in places and occasionally impure. Bad, amateurish engraving would knock the valuation down. Robert possessed more than a thousand firearms—all discharged—from the 19th century. I’d spent the last weeks cleaning each canister with a small white cloth.

Together with the pistols were medical items of the same period, used by frontier doctors to treat an array of maladies one might encounter on a journey west. We made it through several steel forceps, though Jeremy slowed us down with an examination of Robert’s prized artificial leeches. Some of them still had spots of oxidized blood on their exteriors, glistening like pairs of dark brown eyes. The guns and the medical equipment were the base of his collection, the items he had when I joined the enterprise. These, he told me, were instrumental to the frontier project. Objects that controlled animals, as well as people, established an American presence in California.

At noon, the team declined to stop for a meal. We worked our way through the following:

- Pulsometer (Nevada, USA, 1840): 30.

- Ipecac and Quinine Canister (Wyoming, USA, early 1800s): 5.

- Mortar and pestle, prescription residue (California, USA, 1850): 3.

Medical instruments of the past were of particular interest to Robert. In life, my employer studied in the field of gynecology. By studied, I mean that he maintained a private practice with a group of exclusive patients. In his later years, he developed a self-warming silicone speculum, The Pioneer, a device that revolutionized contemporary gynecological comfort. Each device smelled like a different species of California flora: sagebrush, eucalyptus. Robert established a company—Pioneer Obstetrics—that produced the speculum on a massive scale. The device was widely popular, affording Robert and Charlene the ability to move up here, hire me, and mostly retire. In his final years, he saw only a few patients from the community, including myself. I will say that it was convenient. I hardly had to walk two steps to get this or that checked out by one of the masters of the field.

That was before he ascended to the greater plane. I referred to Robert as my employer still, since I didn’t believe Charlene counted as such. Her part of the collection limited itself to old statuettes of American cartoon characters, all of which were held in the easternmost room on the second floor. While Robert’s collection could hardly be contained in the house, I fit Charlene’s in tiny drawers and cheap storage units.

We moved to Charlene’s items just before noon. When I opened the thick wooden door, I winced. Laid out on the table, Charlene’s action figures looked like emaciated dolls.

- Snoopy statue (American, mid 20th c): 176.

- Charlie Brown Collected (1st ed., 1955): 1.

I turned to Jeremy and Trevor while Niko was checking one of the final Snoopys for cracks and holes.

She’s from the Midwest, I said to them, by way of explanation.

Early in my tenure, I caught Robert and Charlene kissing in this room, on my way to repair one of the lesser Snoopys’ ears. The small enclosure was private but maintained the allure of public discovery, even if the only public they really encountered was me. They were younger then. Robert kept his figure well and swam in the pool daily—he was stronger than she was, commanding the shape of the air around him. By then I’d gotten to know him well. I knew the way he flipped the pages of a rare French psalter, for example, or cut open a box of blood-red decanters. I’d barely spoken to Charlene at all. He had her up on the table, a chunky orange pump hanging from her left big toe. She wore a dress that looked too bright for the environment, a short blue sheath embroidered with multicolored thread. Every move he made was deliberate. Charlene flailed around him making loud noises, hitting his back, biting his ear. Her thighs stuck against the surface and periodically she lifted one, producing an ugly sound. I coughed at the doorway so they would hear me. Robert looked embarrassed, but Charlene laughed.

I didn’t know the help was in today, she said to Robert, giggling.

It was a joke because, by then, I lived downstairs. The help was always in.

Sorry, I said, moving to shut the door.

As I left, I saw Robert grab her again, their bodies moving together like sandpaper and rough wood. Robert’s desire for Charlene was one of the mysteries of my tenure. Even after his death, I couldn’t enter that room without feeling bile rise in my stomach. I saw his hand stroking her back, his thin lips pressed to hers.

Devin stroked the last of the Betty Boops with a fibrous wand. She’d acquired far more of them than I anticipated. The team was behind schedule as a result, only through half the contents of the Charlene Collection when they should have made it to the library by lunch. I’d learned—though not well enough—what Charlene could be like with her purchases. Her deliveries often arrived in the middle of the night, slipping by me when I was asleep. I did my best to catch everything before it arrived at her door—I knew that, once it got there, the chance of it leaving again was slim to none. Often, I would find them strewn about her bedroom, flaked with bits of food and drink. One of her Mickey Mouses was sticky with old ketchup and mustard, their residue obscuring his oblong eyes and circular ears. I mostly didn’t bother to clean them, handling each character with latex gloves to avoid getting any of Charlene’s leftovers on my bare skin.

- Betty Boop (Mexican, mid-20th c): 3.

- Betty Boop Ceramic Mug (Russian, 20th c): 4.

Jeremy held one of the Boops up to a magnifying glass. Betty wore a short black dress.

I think my daughter would like this one, he said, laughing.

I felt my cheeks grow hot.

The sound of a loud, electronic bell rang through the wing. The landline hung on the wall lit up red. It was Charlene’s Intercom, an antiquated device connected to phones throughout the mansion. She was the only one who used it, and as she aged, it became the device she used to communicate with me from her bed.

Barbie, she said. Your presence is requested in my quarters.

She let out a laugh at the end of the sentence. Barbie was the name that Robert gave me in the first few weeks of my employment at the estate, after I arrived one morning wearing an old pink dress. By now even the appraisers used it: Barbie this, Barbie that. It still felt like a compliment.

Excuse me, I said to the appraisers. My presence is requested.

I left the team, making my way upstairs to Charlene.

She spent most of the day in bed. When I opened her door, she was propped up against an orange throw pillow with all the blinds drawn. There was a bed with a tall frame, like a canopy if someone forgot the cloth. The only furniture was a small desk that had a large desktop computer on it, which Robert and Charlene shared. The computer’s background had a picture of Robert on it still, smiling at Charlene’s camera. I knew that she kissed it before she went to bed—I’d put her to sleep once, when she fell asleep at the dining room table—like she was saying goodnight to him. I looked away from his screensaver eyes. I could see the faint outline of her red lipstick on his pixelated cheek.

You should have knocked, Charlene giggled. I hate when you catch me off guard.

She raised her hand, motioning me closer. Charlene’s skin was coarse and broken in the places around her wrists and fingers. She’d been thin all her life, but a bout with breast cancer a few years back weakened her. Some days it seemed she could hardly walk. She was double mastectomied: her cardigan lay across her chest, rail-tight, wrinkled up only under the arms.

What can I assist you with? I asked her, raising my voice and enunciating clearly.

Charlene’s hearing got worse and worse. She acted like I hadn’t said a word, tapping her long fake nails together. Even in her advanced age, Charlene didn’t stop getting new ones put on. A manicurist came to the house each month, a young woman from Palmdale, equipped with glue and polymer and the colors Charlene liked. She never got a simple brown or beige. Her nails, sometimes adorned with small gems, were covered in bright pinks, oranges, and one persistent, garish green.

Where are the men now? She asked.

With your items, I said, projecting.

Those old things, she said. If I knew they were going to cause this much trouble, I would’ve stopped buying them!

They’re part of the collection, I said.

They’re nice little things, aren’t they, she said, as though she hadn’t heard me.

Yes, I said.

Barbie, she said. Don’t be dull. I’ve been up here all day by myself.

She acted like it was a choice she had made. Charlene liked to downplay her age and her difficulties around it. She’d found the perfect doctors, too, the ones that would insist she was doing perfectly fine.

It was a busy morning, I said.

Charlene liked me to come up around breakfast and read her the paper. She requested that I put on a few different voices to read the articles, like a play. New big war, I would say in a gruff man’s tone. President bruises hip in China.

If Robert only knew how you treated me, she said.

I flinched. I imagined Robert’s cool blue hands unwrapping a rat’s cage. The understanding built up in his eyes, staring into space. Sometimes I thought we knew two different people, men who switched bodies at night.

My apologies, I said.

Her only response was a vigorous nod of her head. Her dyed hair bobbed in the dark, a bright red orb cutting against the glow from the curtains. She rested her nails on the bedside table, tapping them one by one against the wood.

I left her room and made my way downstairs. Exhaled. I always held my breath with Charlene, like I was going underwater. With the team still occupied with Charlene’s acquisitions, I would have a moment to myself to rest and prepare the items in the library.

The library was the main reason I took the position in the first place: Robert’s books covered at least as much material as the nearest university collection. It smelled of cracked paper and specialized cleaning agents, its windows coated in film that blocked UV radiation. The light was a soothing, artificial yellow. Located in the western wing, its stacks were relatively private.

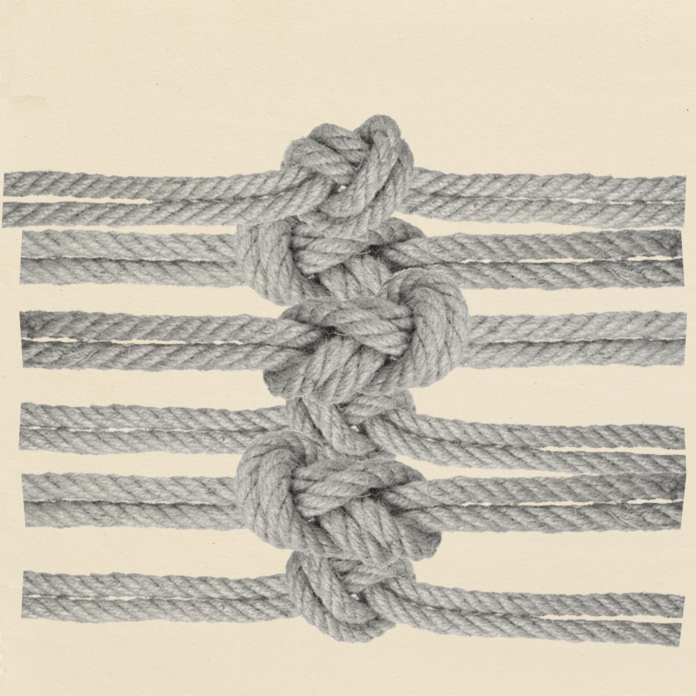

I made my way to the flat file storage, where Robert kept the more valuable items in his collection. He’d amassed a growing number of books on animal trapping before acquiring the objects themselves. Volumes on taxidermy, tanning, and mounting filled the library. There were many strategies, from simple synthetic glue traps to steel-jaw enclosures that fur trappers used as they crossed the Rockies. I imagined that, in the cold, the raccoons and big cats didn’t really mind their fates. They may have even liked it that way, sheltered from the elements, kept in isolation while their fur grew to the ideal length for skinning.

Many of the snares he acquired fit in with previous acquisitions in his collection, with the hunting rifles and primitive animal sedatives. These items demanded a special categorization, a set of alphanumeric codes used to pull up each individual trap with the specificity Robert had required. He would never ask for the normal ones. He wanted the traps that broke a rat’s neck on impact, and he wanted those separated out from ones that used poisons or crates. I sorted by material, too. Wire kept away from wood.

- {45b, 11ax}: Animal trap, no-kill (American, 20th century). 301.

For most of the animal traps, I used a corresponding numeric set to articulate the sweetness of the bait used in the trap and the relative brutality of the animal’s murder. It was the simplest way to categorize the wide variety of traps, spanning from the 15th century to the near-present. The set listed above pulled a variety of salty, sticky lures (45b) and no-kill traps that immobilized creatures until they died of starvation or sleeplessness (11ax). These were used to catch insects, mostly, though by the time they got to Robert the lures were usually dried up. The older ones kept bugs alive in sugar until their natural passing. I imagined them smiling into stillness, glucose coursing through their veins.

I pulled on white cotton gloves meant to shield the objects from my skin’s oils. I unlocked the set of drawers. I knew the team, especially Jeremy, the dater, would want to see the older ones first. These were the ones with the highest monetary value. I grasped both ends of a simple Paiute deadfall snare, a wooden beam mounted on rocks with a twirl of intestinal string wrapped on one side. Used to kill larger animals, the trap was long and heavy. I gathered a few glue traps for good measure. They’d fallen out of favor more recently; their adhesive was indiscriminate. Glue traps often caught animals they didn’t intend to.

The flat file storage also held some of the more vulgar items in Robert’s collection. At first, when I began the position, his interest in erotic art repulsed me. Over time, however, I came to respect his intricate knowledge of the genre. I even came to enjoy looking at them, the different ways the women could contort their bodies and mouths. You can spend your whole life in the narrow seams between paperbacks and decimal points and then someone like Robert comes along and blows your world wide open. The majority were beer advertisements and rare frontier pornography, stretches of canvas that featured near-naked women in various stages of excitement. We had developed a unique classification system for these, too, one that could accommodate the vast selection in Robert’s possession.

We devised a schematic structured around two characteristics: the size of male genitalia pictured, and the perceived variety of pleasure experienced by each figure in the work. This specific combination of numbers referred to a sector of works where the male member was obscured (11), but the pleasure experienced by the partner was a kind of sharp physical pain (010). Letters were added to specify artist, year, and wagon train, if applicable. This way, a barcode could be generated, and a range of prints easily sourced from the archive.

I set four or five of them on the library table, removing the glassine from each mount so the print could be clearly viewed by the appraisal team.

The door of the library opened. Devin, Niko, and Trevor walked in. I was amazed I could tell them apart: each had hair closely cropped to their skulls, their skin the color of light cowhide.

Where’s Jeremy? I asked.

They looked at each other.

He’s finishing up with Charlene in her quarters, Devin replied.

I breathed in sharply. Charlene’s interference in the appraisal process could derail us for a few hours. Charlene had little to no idea how the database worked. With Robert around, Charlene’s negligence had never been an issue; he knew the specificities of the database top-to-bottom. He knew that just one misstep could throw off years of work. Any false identification or wrong application of code altered wide swaths of data. Robert had a justified reverence for the system I devised. We spent lots of time just looking at it in the library together, seeing the way our little codes could get his objects into the correct order. How we could pull up whatever he wanted and whatever I wanted.

Devin lifted each print out of its cardboard sleeve, examining it for nicks and discoloration. He made notes on a slim black tablet. Niko peered at the Paiute snare.

Paiute, 1600, he said, whistling. Never seen one of these outside a museum.

I smiled, my eyes crinkling. I looked sideways at Devin, noticing the way he held a magnifying glass up to the Anheuser-Busch advertisement.

This is the whole sample? Devin asked.

Yes sir, I said, staring at the table.

I was taken aback. An appraiser had never questioned my judgment before. The sample set had to directly correspond to the rest of the items in question. Since the animal traps and erotica comprised a large part of the collection, the sample was especially important: anything left out could drastically alter the valuation.

I knew, in fact, that there were a few objects missing, ones I had never put under valuation. Their inclusion wasn’t necessary. Before Robert died, he moved some of the items into my bequest. Some erotic Western novels and a few animal traps; a speculum or two for good measure. I wasn’t sure if Charlene knew about my side of the collection, so I kept it to myself.

I wouldn’t possess the items Robert bequeathed to me until after Charlene’s death. For several more appraisals, at least, that seemed clear. Charlene had her claws on life. I’ve seen people die before, people like Robert, and they won’t go until they’re ready to go. It’s one of the miracles, the not going. It was one of my personal problems too. I imagined a small cabin in the hills surrounding the house, one that I would build and fill with all the different things he gave me.

Devin put down the print, satisfied.

Beautiful stuff, he said. You must not get tired of working here.

No sir, I said.

The cotton gloves were sticky with my sweat. I switched pairs with my back turned, hurrying to open the cabinets. In addition to the larger pornography and animal trap collections, the library held relics that didn’t belong to any subset, so the appraisers would be able to complete the valuation easily.

- {11b, 010n}: Riders of the Purple Sage (Zane Grey, 1st ed: 1912).

- {45b, 7a}: Artificial leech (metal, American, mid-19th c). 25.

The sun set as we finished up with the last of the steel snares. Jeremy joined us at nearly the last one. Charlene must have given up on him. Or maybe she’d finally exhausted her Betty Boops. The sunlight disappeared from the window. I could hardly see my hands, their fingers illuminated by my soaked-through gloves. Reappraisals always made me nervous.

After reviewing inventory today, the team would retreat in private before issuing a final valuation. We broke before dinner. The four men wandered around outside, admiring the land.

I went downstairs. Even though it was completely enclosed, the air seemed cleaner underground. It was very private. Usually, I stripped off my clothes as soon as the day was finished, lying my back on the concrete. The basement was host to all the weird little creatures that got sanitized out of the upstairs: ants, cockroaches, the occasional rat. I saw a spider crawl across the ceiling, her legs spread. I had a few of them frozen in cornstarch in mason jars I took from upstairs, but I hadn’t perfected the process. Their bodies deteriorated far too quickly. I let the one above me go.

I had just stretched myself out when the black speaker embedded in the wall next to my bed’s pillow turned on. Then came a man’s voice: Devin or Niko.

Barbie, the voice said through the speaker. Would you come to the library for a minute?

When I opened the door of the library, all the lights were off. Through the dimness, I could see the appraisers, sitting around the conference table at the left end of the shelves.

Sit down, Jeremy said. His voice was higher than the others, almost a squeak.

I’ll get the lights, I said.

No, said Jeremy. Charlene, can you get them?

Charlene wasn’t supposed to be here, not yet, not until the valuation announcement. I pulled out a chair, feeling for it. I noticed my hands shaking. In the corner of the room, I felt what must have been Charlene, fumbling around for the switch.

Now, Barbie, Devin’s voice came from my right. You know that we have a duty to investigate all parts of the database. And when something does not correspond to the inventory given to us, it’s an appraiser’s responsibility to note any discrepancies and report them to the board.

Of course, I said. I put my hands in my lap, pinching my stomach. The lights came on.

Laid out in front of us were the traps Robert gave me. Their wires crusted with age. The best ones had bits of fur still stuck to their crevices, where possums and rats and rabbits had been. I saw, floating above one of the glue traps, a strand of my long brown hair. During one of my viewings of the traps, I must have gotten too close, my follicles caught on the lures. I saw another, too, dangling from one of the squirrel nooses. The noose was a specialized trap that used no bait and few, if any, supplies. I put my hand to the clip that secured my bun, wedging it in tighter.

Charlene made her way from the light switch to a chair at the conference table, which she pulled back and sat in easily. I noticed that her hands were still. She looked healthier than I remembered, her cheeks flushed, the hint of a bicep poking through her silk blouse.

I looked down at myself, my lumpy dress, my twisted hands.

I felt the eyes of the appraisers staring at me.

What are we seeing? Devin asked.

It was a gift, I whispered.

Right before Robert died, he came into the library when I was working on dating a new Old Overholt whiskey print. I was in the middle of the stacks. He carried a large cardboard box, one he rolled toward me using a metal dolly. I knew he must have seen me on the cameras set up for library security. I’d seen the cameras and footage before, up on screens lining the walls of his office. He admitted to me, once, that he enjoyed watching me go through the maze of shelves and rooms and objects. He said he liked knowing I was there, navigating the house and making sure everything was in the place that it should be. On the tapes he’d shown me, I looked as small as a tiny bug, skittering through the library’s tall walls.

Robert gestured for me to join him at the table, setting down the cart. By then his movements were short, stuttered. He told me that he’d been waiting to show me something.

They were the finest animal traps I had ever seen. Their wiring was pristine. Each lure maintained its distinct shape. When he said they were mine, or at least mine after he and Charlene passed, I turned to him in awe. We examined each trap until sunrise the next day. I held his hand steady as we set up each trap and lure, watching how it would close on an animal’s neck. Sometimes, even now, I could feel the weight of his small body next to my own.

Charlene cleared her throat. I jumped, startled, but avoided her gaze.

Barbie, Devin said softly. This kind of discrepancy is no laughing matter.

I saw my house on the hill going up in smoke. I laughed.

The Board was known for their frequent revocations of licenses. It was part of their creed. Archivists could not keep any objects hidden from the appraisal process. They couldn’t get too close to the collections either. We were not meant to mistake the items for our own, substituting our devotion for actual possession.

My breath felt hot against the walls of my mouth.

Charlene alerted me to the presence of these objects this afternoon, Jeremy said.

I stared at the traps laid out on the table. I looked up at Charlene and back at the traps. Jeremy placed a greasy string deadfall in front of us, its small strip of lacquered twine rolled around a forked branch. The string, typical for the type of snare, had been dipped in animal fat, which sufficed as a bait. I could smell it still, its thick, dark odor. A large rock was attached to the twine’s opposite end.

Hanging from the middle of the string, I saw a shard of one of Charlene’s pink acrylic nails. Along its rim were four sparkling rhinestones. I looked closer at the traps in front of us. I saw another nail caught in the trap on the side of the table closest to Devin. Its bright yellow ridge bulged into the glue, broken off at its ragged edge, unable to move.

After the appraisers left, Charlene stayed next to me, sitting at the table.

I didn’t know you knew, I said. About what Robert gave me.

I’ve always loved those traps, she said, staring into space.

Me too, I said.

I’ll call a car for you in the morning, she said.

I thought about how we might look on the cameras: like two pebbles caught in the same gutter. Her fingers twitched, hovering over my own. I felt the air conditioning on my scalp. It was better, I thought, to live in the small darkness of the shelves. Better than it was out there. Without my license, access to collections as expansive as this one would be extremely limited. I focused on my breathing.

I looked at the far wall, where I had hung one of the portraits of a naked barmaid. She buckled under the hooves of a large stallion, her mouth open, ecstatic. In front of me, all of Robert’s snares were still set up. The fluorescents in the library glinted off each trap, their steel clasps casting shadows across my arms. The smell of lard mingled with my sweat.

When I went to gather my things that morning, I realized I had nothing at all to pack.