The famous black writer was in town to give a reading, and Coleman was not sure if he would go. He had known the famous black writer for a few years, but only indirectly. They had many friends in common and had gone to the same university, though years apart. The famous black writer had a kind of totally useless fame, which was to say that he was notable among a small group of people interested in highly experimental fiction that was really memoir but also a poem. The famous black writer had built a reputation for pyrotechnic readings that sometimes included slideshows of brutalized slave bodies and sometimes involved moan-singing. Coleman had watched videos of the famous black writer and had felt a nauseating secondhand embarrassment, thinking Is this how people see me?

The famous black writer was handsome—tall, with striking bone structure, and a real classic elegance. He looked like an adult, like a finished version of an expensive product. His hair was quite architectural. The night of the reading, he wore a mohair coat and slim-cut, all-black ensemble right out of a photograph from the 1950s.

Coleman sat in the center of a back row. He had come from teaching his class of interested if somewhat baffled students, feeling as he always did that he was letting them down. Their work was passionate and strange, shot through with a crackling anxiety that manifested in a kind of formal daring. They wrote stories in the forms of Spotify mixtapes, research articles, blog posts, found footage, a dreamspinner, a fortune teller, a set of building blocks with story parts scribbled on the sides. One of them turned in a Twitterbot that dispensed lyrical lorem ipsum at fifteen-minute intervals. They were not writers and did not want to become writers, which felt at once like a relief and a rebuke to him. He felt unable to really steer them in any particular direction, and so he settled for doing as little harm as possible to their strange little selves. This was not the way Coleman had been taught to write. His own education had been a series of brutal corrections and public embarrassments. He had been harassed into line and made to heel. He would not do that to his own students, but still, sometimes, he thought he was failing them.

At the front, the famous black writer sat behind a small table while the bookstore attendant read his biography into the microphone. There was a constant, low-level of feedback from the overhead speakers which were too close to the podium, but no one ever thought to move it or to adjust the volume of the microphone, and so when you listened to the recordings of readings, there was always something sharp layered over the audio that made it unpleasant and uneven. In the room, the sound was less biting but it was there, like listening to two things at once, one trailing just slightly behind the other at a higher pitch, a doubling. After the biography, quite long, had been read, the famous black writer got up and stood for a moment with his eyes closed. Without opening his eyes or his book, he began to sing, quite loudly, a hymn that Coleman recognized as “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.” It was a song he always associated both with his grandmother and with Patsy Cline, whom his grandmother called a Godly Woman, and whom Coleman always thought of as being a lesbian icon though she was not a lesbian. The famous black writer was not a gifted singer, but nor was he interested in sounding good, it seemed. He sang in a warbling tenor that sometimes brightened considerably and broke on high notes, and after a literal minute and a half, he stopped.

The famous black writer opened his eyes, smiled broadly, and said, “Let the church say amen,” and a few of the white people in the audience yelped and said Amen! But in the way that people in the North said it, plural and with no distinct break between the syllables. The famous black writer laughed into the microphone.

“Wow, I’m really in Iowa,” he said.

The famous black writer was from Mississippi, but he lived in Boston, and hadn’t lived in the South since he was eighteen and had left for college. He had a slight Southern accent and was, according to his internet presence, Atheist but culturally Baptist. Coleman sometimes remembered his own childhood going to the small white Baptist church out in the country. He remembered the sermons about Elijah and Luke particularly well, but more than that, he remembered the rasp of the preacher’s beard after service when he came down from the pulpit and kissed all of the children sitting in the front pews, offered to him as if to stave off the wrath of a mighty God. Down he would come, dark-skinned with gray whiskers, brushing his lips across their heads and cheeks and necks, smelling sweet and bitter at the same time. And sometimes, he’d take them onto his lap, and would sing hymns while he held them, the strange hardness of his body beneath the shifting robes, and if they squirmed, he held them tighter, and if they sat still, he dug his fingers into their sides, and the whole church watched and laughed, and the children waited their turns with hard, calm faces.

A memory of the preacher rose in Coleman, unbidden, unasked for, unneeded. It came like a wave, like the full-body recollection of a favorite song. There it was. The preacher’s office. His high bookcases. His music playing. The couch small and dusty. The preacher shedding his robes and showing Coleman how to unbutton his own shirt. One at a time, the buttons came open, and Coleman shivered as the preacher touched his belly. His outie belly button. The preacher said I have one too and unbuttoned his shirt and showed Coleman. His dark skin. The white fur of his stomach, and there, a slightly tubular protrusion, firm and soft at the same time. Coleman touched it, could remember the feel it, how alien another body was to him, who had come from a family where no one touched anyone. The preacher had then laid on him and pressed him flat into the couch and Coleman squirmed and tried to get free, but he could not, and the preacher lay on him for a long time, sometimes grunting, sometimes biting at Coleman’s shoulder and Coleman cried out but the preacher put his hand on Coleman’s mouth and he said, in a quiet and tearful voice, How terrible art thou in thy works. Through the greatness of thy power shall thine enemies submit themselves unto thee. And he stroked Coleman’s head while he writhed on top of Coleman and then he panted and was done, and then he dressed himself and dressed Coleman too and sent him out into the cool dark kitchen of the church which had been built in a recent addition. Coleman ran to his mother who was waiting in the car for him. She had brought him for additional instruction. That’s what they called it. Additional instruction.

“This book,” the famous black writer said, “took me a long time to write. To get the story right. It took a long time.” He looked out at them, his head turning this way and that. The people in the crowd sighed softly, meaningfully. “I’m grateful to this book. It made me better. More in my life. You know? Like, I’m really here. On Planet Earth now. I wasn’t before.”

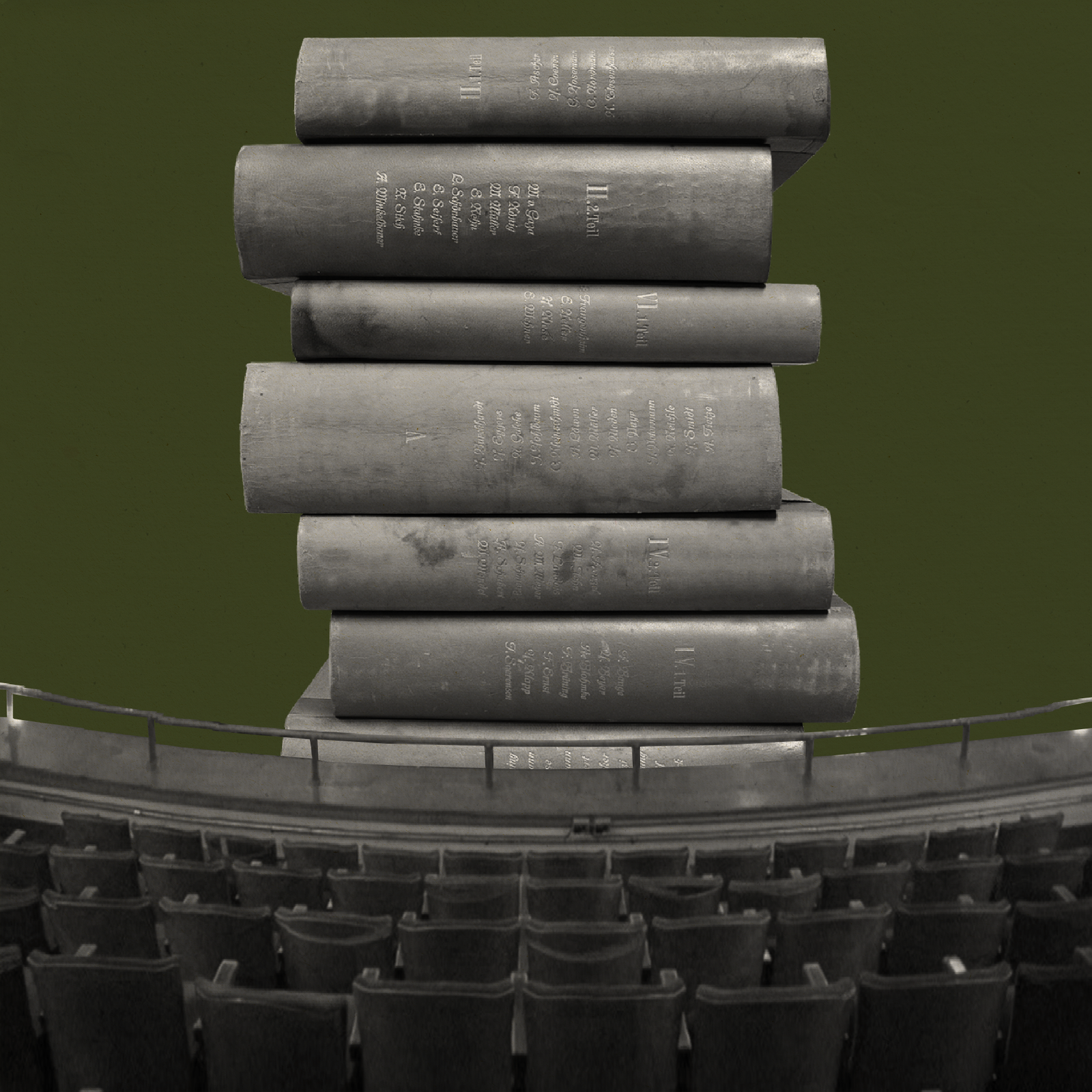

The book in question was a slim blue volume of six essays or stories. Whether they were fiction or not seemed beside the point. Each piece was in the first-person, narrated from some vague point in the future. Coleman had read an excerpt online, thinking the whole time he was reading that it felt vague to him. That the outline of the story seemed diffuse or else was so contrived that it ceased to serve as an actual frame. It felt like he was reading the interior dictation of a very boring person who woke up and had brunch in Williamsburg and thought sometimes, however fleetingly, about the warming world or about race in America, thoughts which themselves were so vague and insubstantial that they amounted basically to aphorisms. That is, the excerpt Coleman had read made gestures toward large thought and feeling, and it said things like, When you are black and gay, the whole world is against you or I knew then that I would be expected to change to suit those around me or My mother told me that I could be gay but that I better not bring a white man home or Walking back from a party in the Bowery, I thought, wow, this is my life, all those slaves died so that I could be here, now, and I’d just let some white man cum in me. Coleman had thought the excerpt was satire. But when he checked the internet, he saw that people had passed the link around in great earnestness and depth of feeling. They felt that something real had been articulated. The famous black writer flipped through the book a few times, and landed on a page and sighed.

“Here we go,” he said, looking up at them. But then, he paused. He took a drink of water. Cleared his throat. Began, “When I was seventeen. My mother told me that my father was dead. I had always suspected that this was the case, but I never knew, for sure, that he was. Most boys grow up thinking of their fathers as versions of themselves they’d like to be one day. I grew up thinking that my father was Bill Cosby or Martin Lawrence or Eddie Murphy, any one of all the black men who came into our lives back then, via television or the radio. I had a whole world of black fathers, but because of the distorting way of media, they were not real. They were digital projections of an idealized black male state, which is to say, they were clowns. And I always wondered where I’d come from. The real man. The human man. The flesh man. Where was he? Out there, somewhere? But my mother told me when I was seventeen that my father was dead. From AIDS. He had been in hospice for many months, and had known he was dying for a year. I would find this out later. I would find out that my heritage was to be, in many ways, the eradication of my kind: black men, gay men, black gay men raised by badass women. That would be my lot in life. I’d be forever a species struggling for survival. I didn’t know that when I was seventeen. But I would soon find out.”

The reading went on that way as the famous black writer described finding out more about his father and about how his mother had kept it from him because she didn’t want him to grow up feeling ashamed. She was not ashamed to have loved the man who later left her. She was not afraid of queerness. But she was afraid that her son would think that something was wrong with being queer or that there was something wrong with him that had caused his father to leave, and so she’d kept it a secret. There was a scene in which the famous black writer discovered his father’s shirt in the back of the closet and draped it over himself and spun around like he was wearing a dress because the shirt was quite big and he was quite small. But his mother had punished him. He thought for a long time that it was because he’d been effeminate. But it was because he had disturbed a shrine of some sort that she had been so angry. The essay was quite narrative, a kind of ekphrasis of dailiness that was common among a group of poets who had recently become essayists and novelists, as though by paying careful attention, they could elevate the tedium of their lives into significance.

Coleman had already read the book and had posted a supportive note on social media, to which some of his mutual friends had responded and had tagged the famous black writer so that he would see the note. And the famous black writer had responded and said something kind. And then Coleman had said congratulations, it’s really great and the famous black writer had first followed him on Twitter and then unfollowed him two weeks later when Coleman published a small essay on his own childhood on the internet. His essay had been about the preacher, who had recently been released from prison on compassionate release. He had liver cancer and was dying a gruesome death that had at once seemed horrible and also like justice. Coleman’s essay was about the preacher and about God and about believing but not believing. The essay went viral in very particular internet niches, and the famous black writer had shared it himself, and Coleman went to thank him privately in a message but found that he could not message him privately because the famous black writer had unfollowed him. It was a strange thing, this retraction of intimacy, and Coleman didn’t know what to make of it. Particularly because he had not asked for it in the first place. It was all petty and small, and it hurt him in a way that he did not know he could be hurt, and this new knowledge about himself made him sad because in some way it said that he was as petty and small as the famous black writer. But perhaps that was the way it always was, that when someone did something to you, you became a little more like them and a little less like yourself.

At a moment of violence in the essay, the famous black writer’s voice trembled and softened as though it might break. He raised his arm in front of his face to defend himself and he shrank away. All of the volume in his voice dropped out, and he began to whisper, plaintively, beseechingly, “I just wanted him to love me and to be loved by me, a desire as old as humankind itself, the longing for kinship, brotherhood, but with all the violence in his heart, he denied me and thrust me out.”

Coleman remembered that part of the book, remembered that it recounted a scene in which the famous black writer followed a white man into a bathroom at a memorial service for another famous writer. They wrestled briefly, and the famous black writer thought that he had made a gross miscalculation, but he didn’t. The other man wanted it too, and they fucked silently in the stalls, but instead of kissing him, the man spat in the famous black writer’s mouth and pressed his face to the wall so roughly that he had cuts on his forehead.

“That’s how one faggot loves another,” the famous black writer read into the microphone that fuzzed and sharpened from the feedback overhead. A jolt, blue electricity leaping from his lips to the mic. “Thank you.”

The applause came in staggered waves, but it built to something loud and forceful. Some people even stood up. The famous black writer stood there with a dazed look on his face, as though he was far far away. Coleman clapped and nodded, and the famous black writer sat behind the table and gave his body a little shake.

“Are there any questions?” the bookstore attendant asked, brow sweating. He had a harried, frustrated look, roaming the aisles as if a question might materialize before him at any moment.

“Yeah, over here,” someone said, and the attendant fetched the mic to them. “That was a great reading.”

“Thank you,” the famous black writer said.

“I was wondering about the way you describe sex. It’s so, like, emotional and forceful and powerful. I was moved. But, at the same time, there’s like, this…potential, for danger, you know? So, I just wanted to know, how do you approach sex in your work.”

“Oh, starting light,” the famous black writer quipped. The audience tittered as if he had physically stroked it. Truly, the audience purred like a pleased cat. “Well, I think, primarily, the thing to remember about sex is that it’s like, fundamentally, an act of violence and an act of union. It’s both of those things, you know? So, when you’re writing, you’ve to just, like, pay attention to all of the things that are happening. You can’t let anything get by you.”

“Makes sense, yeah,” the person said, and then sat down. And someone else stood up.

“What about this question of like, race? You know. I mean. You’re black—”

“I hadn’t noticed!”

Laughter, low, anxious. Someone laughed so hard they coughed and sounded as though they had hurt themselves.

“Oh funny. Yeah, but like. Okay. So you’re black, but oftentimes, because you know, you move through different spaces, and stuff, like, how do you negotiate race and power in all of the spaces you inhabit? And how do you queer and make new those spaces and institutions which seek to exclude you?”

The famous black writer narrowed his eyes and hummed for a moment. Coleman thought the question was stupid, but it was the kind of question people who went to college were always thinking up. Nonsense questions derived from the notion that the personal was political and that the political was personal. More of the trivium of life being made much of. The stupid chatter of neoliberal dinner parties and socialist potlucks. It was the kind of question you asked when the material concerns of life were abstract like Monopoly money or thought experiments. Coleman pressed his tongue to the roof his mouth. Heat filled his nostrils, and he stared so hard into the pattern of the carpet that it went diffuse and fuzzy. His vision went out of focus.

“That’s an interesting question,” the famous black writer said. “I think a lot about, what it means that I’m up here, in front of y’all. You know? A kid like me from where I’m from? Up here? Talking about books? About my life? Words? Yo. I mean, I never saw it coming. And y’all didn’t see it coming either, I bet. How could you? You’re white. Midwestern.” Here, another laugh, the famous black writer relaxing into himself. “But word, yeah, I think about it. I think about it means to be a black body. It’s why I start every reading with a hymn, you know? To center us in blackness. To situate us in the context. I can’t summon my people for y’all if you don’t know us, if you can’t hold us. And yeah, that’s like. Yeah, it’s what I do.”

There was a spontaneous applause then, and Coleman looked left and then right, out among the rows of white people, their hands slapping together and falling apart, the noise so thunderous that his ears rang with it.

Nothing had been said, really. Nothing of particular interest or note, and yet they clapped as though the fundamental structures of their lives had been elucidated to them somehow. But perhaps that’s why people came to these readings, to the famous black writer, to have something illuminated for them even if they were the ones holding the flashlight all along. People believed what they wanted and they felt what they needed to feel.

The thing about prophets, even bad prophets, was that they were always in search of an audience. They were hungry and deprived. If no one listened to your prophecy then you were not a prophet. It was similar to writing in this way. If no one read you, were you a writer? The preacher had been a prophet. He predicted lottery numbers. He predicted health scares. He predicted many things. They gave him everything in return, including their children. Including themselves. He took their homes and their cars. He took out credit cards and bank accounts in their names. He robbed them except it wasn’t stealing because they offered it to him. Coleman was not stolen. He was offered. The essay about the preacher had been titled “The Offering.”

It’s what you called the price you paid to pretend that the world was as you wanted it to be. An offering was a toll for entry.

“What was that hymn that you sang?” someone asked.

“Oh that nigger music?” the famous black poet asked with a mean little laugh. The audience gasped at it. The suddenness of the word which felt like a betrayal to them. Coleman flinched a little when he heard it. The famous black writer preened. “Oh, so now you’re uncomfortable? You listened to all those stories about me getting punched and spat on, but nigger makes you jump? Interesting. Look it up. I’m not a dictionary.”

There were more questions, then, and the famous black writer got more and more comfortable. Skewering people with quips and comments that got slightly meanspirited toward the end. The laughter got more and more nervous. At the end of the reading, there was a signing, but Coleman did not go up to have his book signed. He stood and put on his coat as people trooped up to make small talk and laugh with the famous black writer. Coleman wound his scarf around his neck and went down the stairs and out into the cold.

*

The night was smooth and dark, and the wind felt as though it had come a long way from the end of the Earth. The moon was so bright that he almost raised his hand to shield his eyes from it. He paused outside of the bookstore to check his phone, the emails and messages that might have come in during the reading, and people began to pass out of the store and around him. Some of them talked quite loudly until they saw Coleman and their voices dropped.

“You coming to this after party?” someone asked him, and he turned to find the famous black writer standing there before him.

“Oh, hey,” he said. “Good to see you. Great reading.”

“Yeah?” the famous black writer asked. He raised his eyebrows and took a step toward Coleman. His cologne was rich and dark.

“Yeah, it was good.” They hugged there on the sidewalk. The wind grew sharp. The famous black writer recoiled, shivered.

“Fuck man. It’s cold in Iowa.”

Coleman smiled though his face had gone dry and tight in the wind. Behind the famous black writer, he could see the booksellers taking down the large cardboard poster that had been hanging up, announcing the event. It was no longer necessary and would be pasted up in the elevator along with the other posters from other events. He wondered which poster that was already up in the elevator would come down to make room for it, and the famous black writer looked at him rather expectantly.

“So are you coming to this party?”

Coleman had not intended to go to the party, and his silence must have given this away because the famous black writer shook his head and put his hand on Coleman’s shoulder.

“Come on, man, walk me.”

They turned and went up the street. Coleman knew that the party was being held in the house of one of his former classmates from the writing program. They had graduated back in the spring, but had both stuck around town. For different reasons. Coleman needed the health insurance and didn’t think he could get a good faculty position (which was to say, a shitty faculty position because there were no good faculty positions for adjuncts) without the teaching experience, so he got a contract teaching undergraduates. His classmate was a poet and visual artist, Monroe Baptiste, and he had a small fellowship with a local arts org, doing planning for literary and artist events. It was this reading series that had brought the famous black writer to town. It was strange however that Coleman had not seen Monroe at the reading, at all, and it was further strange that no one from the arts org was doing the walking.

“They left you?” Coleman asked. They had reached a stoplight and were waiting for it to change. The famous black writer shivered in the cold, black wind. He looked to Coleman, and his eyes flashed with fear, as though this cold were an existential threat.

“Nah, I just didn’t feel like walking with a bunch of white folks. After this. You know?”

Coleman did not know what this meant exactly, but he nodded just the same because it was kind.

“Did Monroe abandon you?”

“He had to get ready, he said. But like, it’s fine,” the famous black writer said.

They crossed the street and went along. There was a Catholic church on the corner. The church was long with a broad facade. It had elegant arches and a cross on a high spire. The trees glowed in the streetlights, orange and yellow, impossibly soft like wool. On the bench, there was a man with one leg who sat holding a limp cardboard sign that enumerated all of the awful things that had happened to him and which had warped the dimensions of his life. The writing was quite neat and quite straight though the cardboard had been punched through and bent. They were walking and it was dim, so Coleman couldn’t read the sign except the bit at the top VETERAN DOWN ON HIS LUCK, ANY HELP APPRECIATED. The man started to say something to them, but the famous black writer put up his hand and said that they didn’t have anything and were very sorry and the man said, “God bless y’all.”

There was a moment then, brief as anything, just a moment, when the famous black writer paused. It was short. It was so brief. He hardly stopped at all. It was like he stepped on something unevenly. Coleman saw it happen and saw also the instantaneous correction. He righted himself. They went on.

At Monroe’s house, the party was just starting. Because few people had arrived at the time, the music felt louder than it actually was. Monroe had taken a lot of the furniture out of the living room to make room for, what, a dancefloor? Standing around? Socializing? He and Coleman hugged at the door as the famous black writer went inside.

“How was it?” Monroe asked.

“Oh, yeah, it was great, you know,” Coleman said.

“You are such a judgy bitch sometimes,” Monroe said.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But Coleman had begun to smile a little. His face flushed. “It really was okay.”

“Yeah, I’m sure. Truth be told, I don’t…I mean, I don’t know. Anyway. You staying? Come in, it’s cold.”

Coleman laughed and shed his coat onto the small pile in the bedroom. The famous black writer was in the kitchen with the four other people who had already arrived. The music was quieter now. Coleman leaned against the door frame and watched as the famous black writer, sitting on the countertop, recounted his day, his evening, the reading, the hotel, his lunch at the diner where presidents and candidates visited when they came through on the election trail. He talked about the river, the wind snapping off of it and into the high trees, how beautiful it was, not unlike Cambridge in a way, its sleepiness, the impression of hidden depths and tradition. He said that phrase with a glint in his eye not unlike, a slight quaver in his voice. He knew that he was being a ham, but he had been brought here to do so, to show off and show out.

They were passing around a bowl of grapes, lush, green, large. They passed it Coleman, and he joined their circle. The famous black writer motioned to him.

“On our way over here,” he said, “we passed this man.”

Coleman handed the bowl to his left, to Monroe. The other people in the semicircle were unknown to him. Other black graduate students, he presumed because why else would a black person come to Iowa unless they had been born there.

“And, I swear to God, he called us fucking niggers when we wouldn’t give him money.”

The room grew suddenly quite bright and Coleman stepped back, as if staggered.

“You heard, right? Like, he said that.”

“No,” Coleman said. “I did not hear that.”

“Well, he said it,” the famous black writer said. “He said it sure as I am sitting here.”

“That is so fucked up,” the woman to his right said. “God. That’s so Iowa.”

“Bunch of rednecks,” another of the graduate students said.

The music was a prelude by Clara Schumann. He recognized it quite clearly. The room dimmed again and Coleman felt that he could see again.

“I don’t think that’s what. He meant,” Coleman said. “I don’t think that’s what he said.”

“He said it. Like. There’s no. It’s not subtle,” the famous black writer said, shrugging, sensing then perhaps that Coleman would not be of use to him. “But you know, hey, you didn’t hear it.”

“Was the reading okay?” Monroe asked.

“Man, it was alright. It wasn’t hittin. But that’s okay. They wanted me to like, explain blackness to them. But, hey. It’s what it is.”

“God, fuck. I’m sorry,” Monroe said. The graduate student to his right, the woman, stepped forward and put her arms around the famous black writer.

“We have to come together in times like this. I been saying that. It’s not right. They always other us. But like, we’re not other. They are other.”

Coleman received the bowl of grapes again, except this time he set it on the counter next to the famous black writer. His stomach hurt, and his vision grew cloudy and indistinct again. He went out of the kitchen as they began to talk more about the incident with the veteran. He sat on the edge of the couch arm and tried to catch his breath.

It was what people did, he knew, inventing things out of what was at hand to make it more interesting. To make the world make sense. To order things. It was possible that he himself had simply missed something. It was possible that he himself had simply not heard it. But it was also possible that the famous black writer was just a liar who created and invented things to suit him and his needs. Or else, maybe he just heard that word everywhere. Maybe it followed him through all the years of his life.

Coleman knew then that the famous black writer was the sort of person for whom getting called a nigger was the worst thing to have ever happened to him. It was something that they could never forgive or forget, being called into space and rendered visibly, irrevocably black. Sometimes, in his less generous moments, Coleman wondered if the tragedy of such a moment was the use of the slur or if it was that thereafter, the person who had received it could never again pretend to not know what they were. Was it the slur or was it that the slur foreclosed possibility of merging into whiteness?

You couldn’t in good conscience pretend to be white if you had been called a nigger, no. Coleman thought it was a symptom of something gone wrong in a person if they lingered on being called a nigger. If that was, in fact, the worst thing to go wrong in a life, it said that no matter what else happened, the primary and formative event of your life was an act of violence so mundane that it was hardly an act of violence at all. It wasn’t the slur they feared, Coleman thought. It the loss of the ability to pretend that they were above it. That they lived lives of such lofty beauty that they could never be brought down. And so their revenge on the rest of the world was to fling nigger around and dig it in and keen and show their teeth when they smiled, this particular breed of black people who had once harbored dreams of being white.

It was too boring and too dreary to Coleman. In Alabama, you just sort of expected it. You couldn’t be surprised when it happened. And when it did happen, it stung a little, it hurt a little, and then the day went on. Your life went on. And you could no longer remember which of the people you knew had been the one to call you that and which were the others, and soon that distinction too dropped away because there was something else going wrong.

Sometimes, you didn’t care.

Sometimes life had such abundance of wild and awful things that you had your choice of woe.

Monroe came through the door with seltzer and a small plate of saltines. Coleman looked up at him and felt a bright pain of love and friendship and guilt.

“You don’t look okay,” Monroe said. He tested Coleman’s forehead, and Coleman closed his eyes. The touch was warm and good. He did not feel well, it was true. He drank the seltzer and ate the crackers. The music shifted from Clara Schumann to Jay Z, and it was in passing this invisible, irrefutable line that the party began.

Other people’s steps were heavy on the porch as they ascended and knocked, came in. Everyone hugged everyone else. They shook hands. They brought dishes of food, snacks. Coleman stood in the corner eating the saltines, sipping the seltzer, thinking about the famous black writer and his lie and how it was hard to tell what someone else wanted or needed until they extracted it from you, and was that love? Taking?

Coleman had not seen this many black people in one place in years. He did not go to parties or mixers or to the Black Student Union. He did not go to their readings or to their events. He stayed alone and to himself. He graded his papers. He taught his class. He tried to write and failed to write. Sometimes, he went with Monroe to the movies or out to dinner. Sometimes, he found himself in a café sitting next to someone he knew, and they’d talk, briefly, like two lost people passing in the woods or else out on the vast, churning surface of the sea, flashing their lights to each other through the great dark.

But at the party, he stood alone, watching their shining faces as they talked about critical theory and affect theory and Jung and Audre Lorde and Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison and the differences between James Baldwin and Richard Wright and Beyoncé and Nina Simone and black radical feminism and queerness. They talked like the sort of black people in a story written by a white person meant to demonstrate the gleaming interior of their innerselves, but in fact, they were just like black people anywhere, which was to say that they were anxious and furious and happy and sad and lonely and bright and brilliant and beautiful and hideous and grotesque and fearsome and powerful. They were ordinary. They were young, about to set the world on fire. They were here to show to each other and themselves what they were worth and to hope, perhaps, that their worth would be acknowledged. They were, at the very core of themselves, something new and something old, and it all ran together in Monroe’s room, and Coleman stood apart from them, for once in his life not sad to be watching, but feeling lucky, so lucky, privileged, to witness them.

The famous black writer gave another reading. He stood in the center of the dancefloor right after someone played via their cellphone an extended clip of Toni Morrison dragging Bill Moyers. The famous black writer opened his slim book and read in a voice that was neither poet nor spiritual singer:

“I am alone. I am free. I am alone. I am free. I am alone. I am free. I am alone. I am free. But what choice did I have? At the end of the day, what choice in these events did I have? How could I say that I was free when I had no choice? If I make my home at the bottom of a well and do not ask how I came to be in that well, am I free? No. I am alone. I am free. I am alone. I am free. I am alone. I came to be in this world by way of mysterious and strange circumstances. I continue to be in this world by way of radical self-love and via the love of those who see me. And so, I am not alone. I am free. But I am not alone. Because the two categories are mutually destructive. We come to be free by being loved. We come to be loved by being free. And so, I am not alone. And I am free. And I am loved.”

They all watched the famous black writer read. Coleman waited for it to end, feeling uncomfortable, densely uncomfortable as he remembered, against his will, the rasp of the preacher’s beard, the heat of his mouth, the pressure of his teeth biting. Remembering how his mother had quietly driven him home, the rising hills covered in pine and spruce. The deep, vegetal beauty of Alabama lifting all around them in soft green waves. The music on the radio “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” or “How Great Thou Art.” Mahalia or The Blind Boys of Alabama or someone else. They did not listen to secular music, only to God’s music, what the famous black writer had called Nigger music. Coleman remembered it and wished that he could stop remembering it. But his nose filled with the smell of his mother’s light perfume, lilac, and the cigarette burning in the ash tray, left there, forgotten. She hadn’t even remembered to hide it from him.

The applause was both louder and more stilted than the reading at the bookstore. Coleman set his plate on the window sill. He set his cup on it. Then he along the edge of the crowd and collected his coat. The famous black writer was answering questions in the center of the room. The music pulsed around them.

It was a stupid thing to stay at this party. To have gone to the party in the first place. It was a stupid thing to have thought of the preacher at all. He had died recently. The cancer had killed him. It took a long time, longer than Coleman had thought, but it had killed him.

Coleman went down the steps and into the street and he walked along it, not on the sidewalk, but in the street itself, watching cars come toward him.

Coleman thought of the all the prophets in the world. All their glorious singing. And all of the people who burned to make their offerings. What was it worth? What did they see except vague and mysterious shapes attaining and losing form in the smoke that rose from the ash?