In the spring of the first of the seven quarantines, there lived a young man in a small house on Lantern Drive in a small town in Washington state. He lived there with his mother who loved him very much but worried constantly about him and, after he left for work each day, she would stand on the threshold of his room, heave a great sigh, and slowly shake her head at the life of the son she had birthed who lived therein. His name was Little Nico and he was twenty-one years old.

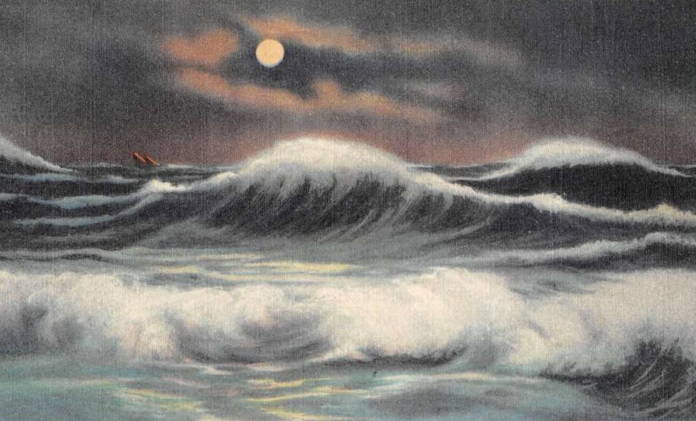

Nico worked every day as a line cook at a restaurant up the freeway until, on the eve of the first lockdown, he was laid off along with all the rest of the staff there and many others across the state, the country, and around the world. It was a time of great change. Holding back tears, he walked slowly across the parking lot, turned the key in his father’s truck, and headed immediately north and west on Ocean Beach Highway, towards his grandma’s trailer where it sat on the Long Beach Peninsula, facing the Pacific and the far, gray edge of the world.

It rained all night. He called his mother and they argued on speakerphone as he drove through the rain, both crying as they argued, as was their way, she begging him to turn around and he ignoring her requests, speaking over her and insisting again and again that he was stupid and a failure and a hopelss waste of life.

He crossed the river at midnight, the great bridge eerily empty above the spring-flush Columbia.

“I’m crossing the bridge,” he told his mom. “I’m a fucking loser. I just want to leave, to leave and go away forever.”

“You’re not supposed to travel!” his mom replied. And indeed a DOT sign flashed ticking at the bridge’s peak: “STAY HOME. AVOID TRAVEL. SAVE LIVES.”

Still they argued on as he drove and with intensity ever greater until, reaching the stormy coast, Nico drove up the first approach he found, drove directly out onto the sand, leapt from the idling truck, and threw his cell phone into the ocean. He watched its light sail over the black waves, his mother’s begging voice still audible a moment longer, then not. Relieved, he heaved a sigh of his own, turned around, and found laid out in the sand behind him the body of a seal whose head he had crushed driving over the approach. Her long, dark body glistened, otherwise pristine in the blinking hazard lights of the truck.

Nico stood frozen, horrified at what he’d done. He then watched as the dead seal raised her partially caved-in head and stared back at him through her good eye, some light still glowing there.

“You have returned to us,” she said. And it was true, for Nico had often spent his summers growing up here on the peninsula at his grandma’s trailer, summers and Christmases and weekends, periods when his parents’ lives had been too stressful for him and he’d wound up here. A nervous, sullen child, he’d trailed his grandma like a rescue dog through the beachgrass of these days, crying when he lost sight of her, wetting the bed when he could not sleep beside her. He had seen seals before but only as curious heads watching from out beyond the breakers. This was the first time he’d seen one up close.

“I didn’t know where else to go,” he said.

The next morning he awoke curled in the cab of his truck parked beside his grandma’s trailer. Her birdbath tumbled beside him into her raised beds high with weeds. Inside he found his grandma sick in bed, feverish and dehydrated, the once spotless trailer now stained and rain-warped and fallen into disarray.

“Little Nico!” she said, finding him knelt there in the shadows of her bedroom. “What are you doing here? I’m sick, you shouldn’t be here. You should go home.”

“I’m here to help you, Grandma,” he said. And despite her protests, when his hand found hers beneath the soggy sheets, a guilty smile broke across her face.

“Oh Nico, my little Nico.” Her voice was faint and raw and broke often into coughing. She fought to breathe. The waves crashed in the distance.

For three days then Nico did not leave the trailer but cared for her always. He spooned food into her mouth, brought her water, pills he found in her cabinet, the only thing that helped her sleep. He carried her to the bathroom when she needed it (which was almost never) and set the radio to the local Catholic station that now played only rebroadcasts of old hymns and vespers, their live programming suspended indefinitely. Each time he left her room, he nudged the volume a little lower.

On the third day, he was washing dishes in the evening when he broke a glass and cut a gash up the side of his hand. Finding no band-aids and dripping blood across the floor, he taped a wad of paper towels over the cut, held his hand at chest-level before him (to slow the bleeding), and stepped out into the cool night air.

Standing on his grandma’s porch, he saw a campfire burning across the way, over the fence of the blackberries and chicken-wire dividing the trailer lots. Three figures stood around the fire, a man and two women. They noticed Nico almost immediately, one of the women pointing at him and whispering to her companions.

“Uh…hello!” he called to the three figures in the night.

The first woman, younger, smiled but did not reply, whispered further to the man who faced the fire. The other woman was older, and pointedly did not smile but frowned stoically into the evening, the world, and at Nico himself.

“How is she?” the older woman called to him.

Nico glanced towards the trailer behind him. “Uh…she’s okay,” he said. He said that her cough was bad if they couldn’t hear it, that she only ate a little, slept as much as she could. He said he’d been giving her Tylenol for the fever, other stuff too, but admitted he didn’t know much about it, how much was safe. The wind stirred the trees above them and bellowsed the fire to glow upon the figures’ faces. The man’s eyes caught Nico’s.

“She’s not coughing now,” the older woman said.

“Uh, no. She’s asleep now.” And then: “I think she might be dying.”

The older woman nodded. The waves.

“Hey,” called the man, “what else you giving your grandma over there, besides that Tylenol, huh? What all else you got over there, son?”

“What?” said Nico. “I don’t—are you asking me to give you some of my grandma’s pills?”

The older woman turned, walked back into her trailer.

“I’ll pay you,” said the man

“Jesus Christ,” said Nico, and he felt his cut hand throb.

“Don’t be like that. You aren’t the only one having a hard time out here,” said the man, “you and every other out-of-towner showing up now, with your little face masks, bringing God-knows-what with you. You know my ex-wife just died?”

“Oh. I’m sorry,” said Nico.

“Yeah well, we didn’t talk that much. But I still thought about her every day, felt her presence out there somewhere, you know? Imagined what she was doing, even if we didn’t talk. But that’s gone now,” he said. “Now it’s just an emptiness.”

The two had to raise their voices to be heard across the space between them, over the fence, and so their conversation echoed a little in the night.

“How—” asked Nico, “was it—the virus—”

“She was a seal,” the man said, and his eyes fixed hard on Nico’s. “She didn’t die of no coronavirus.”

Nico searched the night around him, mouth open, searched for what to say. The younger woman’s expression changed as she realized something.

“I may have me a season’s share of ex-wives,” said the man, “but none of ’em were like her. And not just because she was a seal,” he said. “So come on. Help a local out. You said yourself your grandma’s dying. Why let her stash go to waste?”

Nico held his paper-toweled finger throbbing at his chest where the panic swelled. He reached with his good hand for the pocket where he’d once kept his cell phone but then remembered. The panic turned to anger. He clenched his good hand into a fist.

“No. No,” he said. “What the fuck? No, listen, I’m not gonna—”

“I know you,” said the younger woman, interrupting just as something was about to happen. “You used to come and stay here with her, when you were a kid, right?”

“I—yeah,” said Nico. “Yes, I did.”

“You’re Little Nico,” she said. And her smile grew wider still.

Nico said nothing.

“We’ve met before,” she said. “You played frisbee with me, right here, or over there actually, in the grass over there. Must have been ten years ago. Do you remember? It’s okay if you don’t. I was about this tall then, frizzy ponytail. It was my first summer here and I was miserable, bored as hell. You seemed a lot older than me then but it was probably just a year or two, huh? I’d see you over there at your grandma’s every day. And then one day I asked you to play frisbee with me. And so you did.

“And I didn’t even know how to throw it,” she said. “I’d just whip it off in any direction, and then you’d walk over and get it. Every time. You did that for—I feel like it was hours. One afternoon,” she said.

Nico stared at them both, quietly astonished. The man said no more but neither did he look away.

“I…I don’t know if I remember that,” Nico said. “But—” He searched his memories for something like what she described but they all seemed to dodge away, like animals from the light.

The older woman reemerged then from her trailer, a first-aid kit in her hand. The door of her trailer clapped closing behind her and the sound of it roused Nico’s grandma, and Nico heard her stir and begin to cough once more inside.

The older woman beckoned for Nico to meet her at the fence. She took his hand in hers, cut away the paper towels, cleaned the gash, and dressed it in fresh gauze and tape. When she’d finished, Nico turned his hand over to examine her work as the coughing continued behind him, and he thanked her, but the older woman only nodded, indicating the source of the coughing.

“Better go take care of that,” she said.

And he nodded, eyed the three figures stood quiet in the night once more. He gave a final wave and went inside.

The wind stirred the trees and the sparks flew up into the sky. The coughing eventually stopped.

Later that night there came a tapping on the kitchen window. Nico, still up wiping his own blood drips from the floor, cranked the window open, and into the screenless frame beyond it he saw arise a hand there, square of twenties folded in its fingers. The hand waited. Nico stared at it a long time, then got up. He returned a moment later, took the money from the hand (causing it to open) and in the open hand he placed three white pills. The hand closed around the pills, lowered slowly down once more. Nico cranked the window shut, the night outside grown cold.

But still he could not sleep, only tossed and turned on the cushions outside his grandma’s door. The waves seemed so loud sometimes while others he noticed them not at all. When he could stand the weight of life no longer, he rose, took a shovel from the raised beds, and drove his father’s truck back down to the approach, to where he’d thrown his cell phone in the ocean and spoken to the seal.

He trolled the night dunes with a headlamp, scoured the beach for any sign of her, shovel in his good hand. A cough tickled his throat.

He never found the seal, only a thin trail of blood between the approach and the sea. It was not clear which way it led.