My friend Puma had an opening the other day for her solo exhibition at a gallery in Mitte, Berlin. It has become a kind of cliché in contemporary art to present the explicitly sexual in stone-faced ways—think of Jeff Koons’s Made in Heaven, or Tracy Emin’s My Bed—and Puma, who was always a little late to the party, was doing so here. The exhibition, called Critique My, was a white room with a dozen paintings of men holding their penises; tenderly, almost. The paintings, oil and tempera on wood with accents of gold leaf, were rendered in the flat perspective of medieval iconography. The juxtaposition was deliberately jarring; the level of hostility present in the creative act, ambiguous.

My date for the evening looked at the paintings and then said to me, “what’s with all the dicks.” Puma had been working with dicks for a while, though it was, in her words, “an investigation into modes of subjugation and power, representation and distortion, and a way of taking control—not by trying to recover or reclaim a type of power my gender will never be afforded in my lifetime, however. Such an attempt would be an invitation to further subjugation, a misplaced, utopic wish. So instead, I take the dicks as I can get them, and the dicks become me.” It was a rhetorically lazy statement, although I thought I sort of knew what Puma was aiming for, still—slap a fuzzy artist’s statement on gallery letterhead, and you can justify most anything.

If I were to do something like that, write about dicks and the like, I’d never be able to escape it. Literature is a conservative art form after all, still fairly wedded to the imperatives of narrative, description, and representation, which perhaps is what people— myself included—like about it. In any case, here in the gallery space, a gold-leaf penis stared back at me, hard. The man in the painting held it up and out so that it pointed at the viewer, his own gaze directed down at the appendage as if surprised to find it there. His longish hair hung down, obscuring his face, so that the pyramidal composition of the painting necessarily drew one’s gaze to the foregrounded penis.

◆

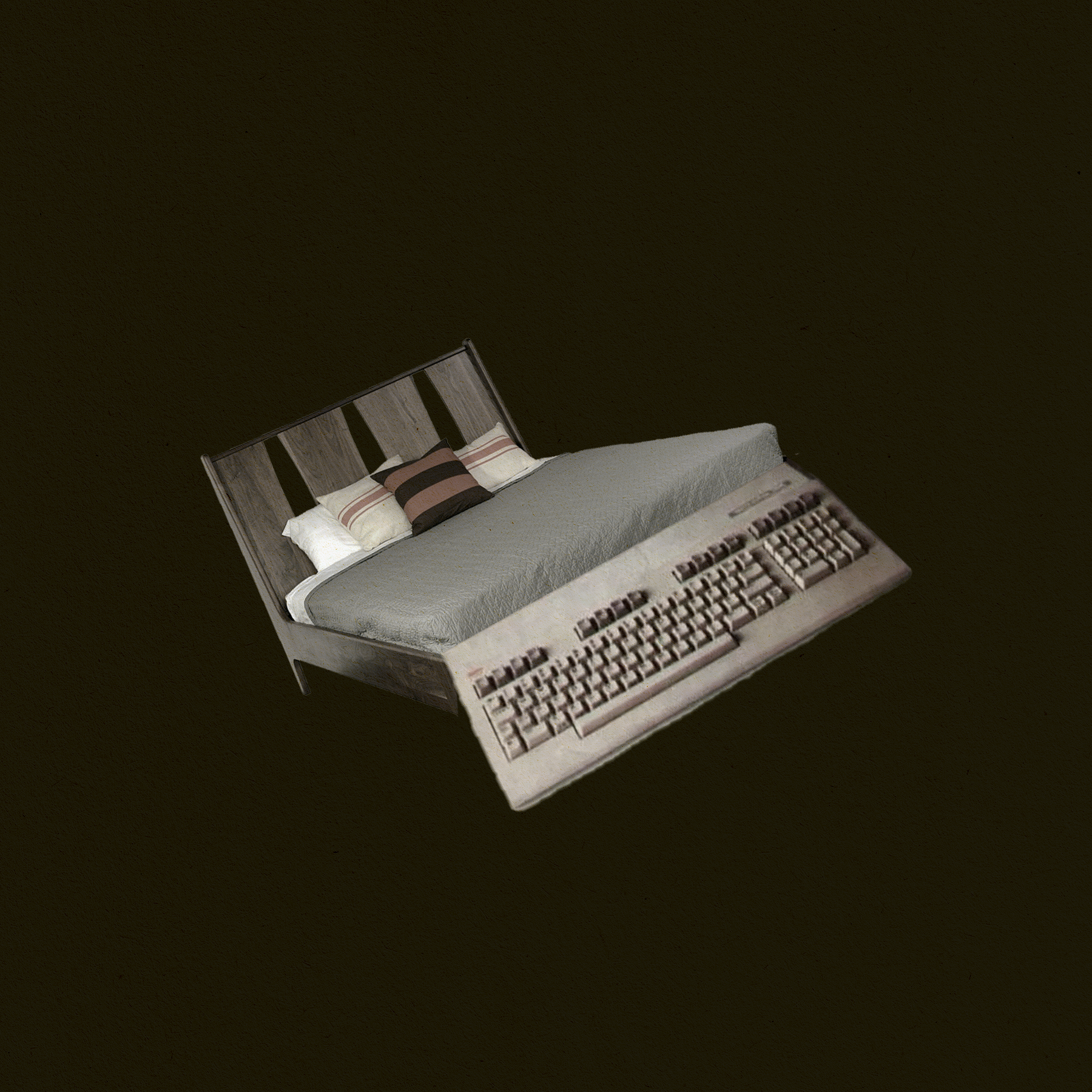

The other night I couldn’t sleep, and rather than read the news on my web browser or browse the web searching for news on how distracted we all are by browsing the web, I went to a website for an American women’s magazine, knowing hair and makeup tips would make no demands beyond asking me to believe in the time-honored notion that if I bought more when I felt bad about myself I would be prettier, ergo less inadequate. So I visited the website of this fourth-wave feminist mag, with links to articles such as “What Your Topknot Says about You,” “Fifteen Ways to Rock a Romper This Summer,” that sort of thing, when I came upon one with the headline: “Why Dick Pics Are Always Awful,” and I clicked.

There has been a phenomenon in recent years of men sending dick pics, uninvited, to so-called outspoken women who use Twitter to speak out. After receiving a random pic, one woman had apparently flipped the narrative and was now making money off a Tumblr she’d created, called Critique My Dick Pic. In the interview with the women’s magazine, the site’s creator said that people would send her pictures of their dicks, and she would give them a letter grade based on the photo’s composition. (The letter grade on the photo’s composition and not the dick was, I imagined, an attempt by the creator of the Tumblr to protect the egos of those who submitted, by making it clear that this was not a size thing.) For thirty bucks you could get a guaranteed review on the site, for fifteen, a private one over email. I had never heard of this Tumblr and so clicked on the link with a combination of sociological curiosity and natural prurience. The photos weren’t erotic—or at least I didn’t find them arousing—but rather, funny: there was such, well, naked need in the pictures, a desperate, reductive, almost plaintive wish to show oneself. A photo of a flaccid penis with a red bow tied around it. A person wearing a strap-on gazing proudly at the camera. Six-pack abs and a thin, erect one. A meek one, half-hidden behind a thicket of hair. Looking at such flagrant representations of the self was more interesting and less demanding than reading tips on how to make one’s pores look smaller, so—even if I did wish for smaller pores—I spent a good ten minutes clicking through the first three pages of the Tumblr, when I happened upon a photograph of someone I recognized (though to be clear what I recognized was his face, which was turned away from the camera, and not his dick, which was turned toward it).

In the sterile white box of my Berlin bedroom, only two page-clicks in, I came across a picture of someone I had slept with: Federico. He was a man I knew during the brief period I lived in Santiago de Chile, a corporate attorney from Buenos Aires who was sophisticated in that entitled way that allowed him to feel entitled to everything. As a woman who was always apologizing when other people stepped on my toes, I was drawn to his sense of entitlement and wanted to bask in his blitheness, as though I might absorb some of its power through sheer proximity, even though I knew that’s not how this sort of thing works.

We had a great two months together, easy and uncomplicated. He was attentive in bed in that way some men are, where they make it about them; but, since neither of us was looking for some deep soul connection, I wasn’t too bothered by how his ego was wrapped up in my pleasure; I felt entitled to it, like he did. I’d spend my mornings editing medical textbooks from home and afternoons wandering the cafés of Providencia, meeting Federico in the evenings for ceviche and pisco sours at any one of the innumerable chic Peruvian restaurants in Ñuñoa, where I’d let him buy the two of us dinners I could never afford on my own. Money for him was such an abstraction that it excited me—not the money itself, for the way I lived my life around him wasn’t all that different than the way I’d lived in other relationships, or alone, really—but the freedom from worry the abstraction of his wealth represented; that was what seduced me, the idea that sums I’d normally fret about were just as easily there for forgetting. I know of course that nothing is ever free, but it was fun while it lasted, fun precisely because it wasn’t something to be taken seriously. He could be kind, too, although there was a remote sadness to him, kept tucked away in a pocket of unknown provenance. It was something I intuitively understood and felt a certain affection toward, as I had my own little purse of grief, one in which I kept tiny coins with no real tender. So I was glad we could give each other this light summertime fling.

Still, after a few weeks, when it became clear we had nothing in common and I could no longer tolerate my discomfort over playing princess-to-be-pleased, we parted ways in a friendly manner and never saw each other again—losing contact without bitterness, but also without any special longing.

Years had passed and there I was, unable to sleep, while Federico’s body seemed to stare back at me from my screen: the particularities of his pigeon chest, those renaissance hands and long limbs, along with his carefully presented, fully erect penis. The photograph was a full body shot, a black-and-white image with Federico in repose and soft light coming through the window; it was a genteel image and seemed carefully produced—so much so that even the name he had chosen for the photo was fussy: Impromptu, he had titled it, although his computer’s camera (or current partner) had no doubt needed several attempts to get the perfect angle for the portrait. The only measure he had taken to conceal his identity was to turn away from the camera, letting his dark bangs fall forward, obscuring his eyes. Below the image, the author of the Tumblr had given his photo an A- and called it “intriguing.”

His body had a particular morphology that I’ll never forget—in part because I was perhaps nostalgic for his actuality, but also because his torso was delicate in a way that reminded me of one of my favorite paintings in the Prado, a late fifteenth-century portrait of Christ by Antonello da Messina, possessing an eroticism both exquisite and unsettling, especially in da Messina’s masterful rendering of Christ’s flesh.

In my last year in Madrid when I lived a short walk from the museum, in barrio Lavapíes, I used to stroll through during the Prado’s free opening hours before meeting friends for dinner, waving hello to the da Messina, the Goyas, the Raphael, the Velázquez. There was a certain delight in the causal consumption of so much greatness; it felt extravagant in a way that my life was not, the equivalent of, had I been able to afford such an indulgent and impractical gesture, populating my tiny apartment with multiple bouquets of fresh flowers.

This painting by Antonello da Messina was more erotic to me than any other that I’d seen. It was executed in a mixture of oil and tempera on wooden panel, the same techniques Puma had cribbed for her Critique My exhibition. Thinking of da Messina’s painting as I stared at the image on my laptop of the man I figured was Federico, I felt certain that what I was looking at was a pic of Federico, because his body had the same peculiar contradictions as da Messina’s Cristo: a porcelain chest underlining the ardent masculinity of his face and clear, taut lines delineating the features of his neck.

In the painting, Christ is seated, naked, his genitals discreetly covered by a loincloth, his head tilted back, mouth agape, in agony from the stigmata—one wound piercing the space between his ribs, the other, his left hand. An angel of indeterminate gender embraces Christ from behind, wrapping a regal blue cloth around his torso while looking away from the viewer in sorrow, as if no amount of succor could comfort Christ in his agony. And well, the angel is right, because Christ is already dead as the painting’s title reveals; despite the gangrenous pallor of Christ’s skin in the image, I always forgot that the depiction of his body was not one of suffering but one of repose, of death, so enraptured was I by the beauty of the image. Christ’s dead body has been depositioned, and yet the presence of the living angel staring back at us, confronting us with this physicality, made the image seem, to me, irredeemably needy. Appropriate, then, that although the painting in the Prado was entitled Cristo muerto sostenido por un ángel (The Dead Christ Supported by an Angel), in Italian it was better known quite simply as Pietà.

As the angel lifts the heavy body, da Messina paints the loincloth not squarely across the hips as in most paintings of Jesus, but over the front of his thighs, as though the loincloth has ever-so-slightly slipped, the shadows and the blood from the stigmata drawing the viewer’s gaze toward the figure’s sex, his humanness. This was the endless allure of the painting and its tension, as the dynamic between the entreaties of the living angel and the carnality of the fallen god felt urgent and impossible all at once: there has never been a death so desirous.

There was something of this contradiction inherent in Federico’s portrait and, I realized then, in looking at his pic, also contained in Puma’s paintings, rendering them almost humorous. It seemed to me that in trying to conceal his vulnerability in the photo, Federico had exposed it: it was there in the lighting and the awkwardly flattering pose, which, in its studied casualness, held forth a transparent wish to be perfectly seen. Or maybe I was projecting, because I needed to believe: that there was some deeper meaning behind him taking and sending and having someone post online and grade a picture of his dick, when perhaps his actions were like what I overheard a woman at Puma’s vernissage dismiss the paintings in Critique My of being: without interiority. Here was a presentation of his power, an erect penis, held forth, but the immutability of the invitation and its failure to be met left me lying there, half-awake in bed, with a benumbed sense of pity. For him or for me, it didn’t matter; almost. This is my body, which has been given up for you, I thought, taking one last look and then closing my laptop.