“Con Safos Rifa” by Lou Mathews is an excerpt from the novel Shaky Town (2021, Tiger Van Books). All graffiti inked by the writer.

◆

There were nine of them on the roof. They all wore the St. Patrick’s school jacket, nubbly green wool with white vinyl sleeves. It was a cold day for March, for Los Angeles, and most of the boys kept their hands jammed in their jacket pockets. The wind reddened the cheeks of the white boys.

From the roof they had a good view of the south gate, the black asphalt basketball courts, the red dirt running track around the football field and the fan-shaped sweep of the surrounding chain-link fence—all of the places the boys from Hamilton High School would have to cross on their way to the fight.

They could see the tops of the Hamilton buildings, across the freeway. The Hamilton boys would be ganging in the yard, they would cross through the walkway, the long pedestrian tunnel under the freeway, come down Salsipuedes Street to the edge of the campus, jump the fence there and cross the football field. St. Patrick’s was a new high school, dedicated three years before; this year the school would have its first graduating class. Seven of the boys on the roof were seniors, members of the inaugural class. This was the first fight in the history of the school.

The reasons for the fight were not entirely clear. There had been slurs, casually exchanged since the opening of St. Patrick’s, the usual tensions to be expected from proximity, but these had never progressed to a flashpoint before. Few St. Patrick’s boys lived in the immediate neighborhood; once school was let out, a half-hour before Hamilton was dismissed, most headed for their bus stops. There was only one place that could be considered disputed territory—the huge car and railway underpass below the freeway, adjacent to St. Patrick’s. Smokers from St. Patrick’s hid there in the morning. Hamilton boys came there in the evening to write on the immense walls of the underpass, but so did many others. Most of the 600-foot walls were sprayed with a tripartite running argument between 42nd Flats, Avenues, and White Fence, three gangs from Shaky Town.

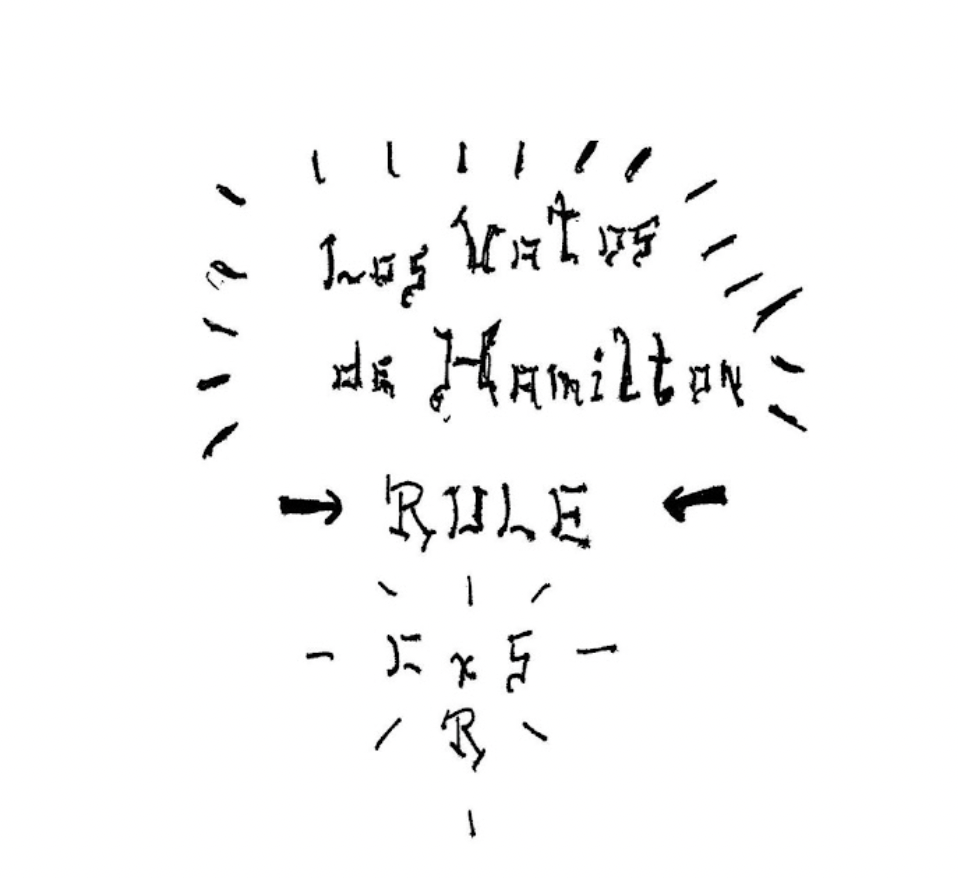

Interspersed, at lower levels, were Hamilton signings. A recent message had been defaced. The original tag said:

Con Safos Rifa, or C.S.R., accompanied nearly every message on the walls. Roughly, it meant: Same on you, anything you write or say bounces back. Con Safos Rifa had been scratched out and a new message appended:

While it was not certain that a St. Patrick’s boy had done this, the choice of words and crude lettering style made St. Patrick’s suspect and may have been cause for the attack upon two St. Patrick’s freshmen: Chuey Limón and Benny Garcia. Chuey and Benny had been beaten up in the tunnel under the freeway that led to Hamilton. There were complications, however. Besides being St. Patrick’s freshmen, Chuey and Benny were also lifelong residents of Toonerville, a barrio on the west edge of Glendale, which had a long, historical enmity with the Shaky Town neighborhood, a neighborhood that provided Hamilton with many students. Also, Benny had thrown firecrackers in the tunnel.

The only person who probably knew the actual reasons for the Hamilton-St. Patrick’s fight was Frank Sanchez, and Frank was not talking. Or rather, Frank was not clear. The first thing he was not clear about was the actual challenge. He did not say whether St. Patrick’s had challenged Hamilton or if Hamilton had issued the invitation. He had simply announced to a number of seniors and a few juniors he could trust, that “There’s a rumble on. Saturday. Noon. Those punks from Hamilton can’t get away with it. We’re going to kick their cojones.”

Frank Sanchez leaned forward against the parapet out across the football field. At his feet was an open brown gym bag. Frank prodded the bag with his toe. There was a clink and a dry tumbling rattle as he shifted the bag closer. The boy next to him, a slight, big-headed boy named Jim Wylie, stared down at the gaping mouth of the bag and the short lengths of pipe and rusty chain.

“I didn’t bring anything,” he said. “I thought it was going to be fists.”

Frank was fingering the long hairs in the crease between his mouth and chin. He twirled them together and tugged on them, pulling out his lower lip until it looked like the spout of a pitcher. He nodded solemnly. “What do you think they’ll have?” Jim asked. Frank released his chin hairs and shrugged. His heavy-lidded eyes and round face were placid. “Same stuff,” Frank said. “Maybe some bats. Some sticks. Aerials. Like that.” He prodded the bag again until it clanked. “No knives. No guns. We agreed on that.”

Three boys squatted in a corner, backs bent and heads tucked so they were below the level of the parapet, and passed a cigarette. The boy holding the cigarette kept it cupped and waggled his hand vigorously so no smoke appeared, and when exhaling, he blew down into his jacket. The boy who was next to him popped his head up and looked in all directions before hunkering to accept the cigarette. He had a round, flat face, a long neck, and ears that stood straight out from his head, and when he got up to look around again, it made the blond boy holding the cigarette, Kenny Culver, think of something funny.

“Casey,” he said, “You look like a fucking radar.”

Kenny put his fingers behind his ears, pushing them out like wings, and swiveled his head in small, metronomic jerks, “Radar head.”

Casey took a deep drag, squinted at him, and gave the finger.

Behind the smokers, two juniors, John Martinez and his brother, Ralph, sat with the other football players, Don Cherzniak, a heavy, slump-shouldered boy with a spatulate nose—a defensive lineman—and Sandy Furillo. Sandy was a red-haired, handsome boy with the gaze of a Collie—a long nose starting high on his forehead, and close-set eyes. Sandy was a flanker, the Martinez brothers were offensive linemen. The other three were watching Sandy, who stood in the middle of the roof, swinging a bat. Sandy tapped the bat on an imaginary plate and took his stance, squinting at an imaginary pitcher. His elbow cocked, his front foot picked up and he strode forward. The bat wheeled in a level, hissing arc. On the next pitch, Sandy squared to bunt. As his hand slid up the barrel of the bat, he changed his mind, and instead of leveling the bat in front of him, he brought it overhead and smashed it down on the graveled roof. Cherzniak’s face split in an open-mouthed grin. Frank Sanchez said, “Shut up. Somebody’s coming.”

Someone was banging up the three flights of steel steps that led to the roof. Frank leaned over the railing. A short, freckled boy carrying a long piece of pipe had reached the landing just below. Frank said, “Bobby, what are you doing?”

Bobby looked up at him. “Did you see them yet?”

“Where’s Reuben?” Frank asked.

“He’s still watching the street.”

“Get back,” Frank told him. “We’ll yell if we see them.”

They were all at the railing now. They watched Bobby descend and walk back toward the gate. Another boy, tall and frizzle-haired, was there. Bobby waved at him with the pipe, “Get back, Reuben.”

“Where are they?” Reuben called. Bobby made a shushing noise, bringing his finger up to his lips. Sandy said, “What time is it?”

The Martinez brothers checked their watches. “Quarter of,” Ralph said.

Cherzniak said, “Where the fuck are they?”

Frank said, “We told them twelve. They’ll be here at twelve.”

Jim Wiley looked around the group, counting. “Do you think any more of our guys are coming?”

At five to twelve they were all lined along the edge, staring out across the playing field. The wind was snatching up powder from the track, whirling it into dust devils at the north end. Beyond the track was the chain-link fence, the slope and Salsipuedes Street below. There were two cars parked on the right side of the street; a vacuum cleaner repair van was parked facing them. Otherwise, the street was empty. Twelve exactly. Bobby and Reuben ran up the street toward the south gate, yelling. A green sedan was cruising up the hill, behind them. Two more sedans, white ones, rolled down the center of Salsipuedes Street. All the doors of the vacuum cleaner van burst open and four men in sweatshirts, jeans and sneakers, ran toward the fence. They scrambled up the slope, hit the fence and swung over, almost in unison. One man, in a sportscoat, remained with the van, standing behind the open driver’s door, speaking into a radio microphone. A uniform car came onto Salsipuedes, then another, heading for the tunnel, their lights blinking. “Oh shit,” Frank said. He tore open the weapons bag and started dropping pipes and chain down a standpipe. The plainclothes cops were halfway across the football field.

The boys were halfway down as the detective put his foot on the first step and raised the bullhorn. “All right,” he said. “You’re surrounded. All of you. Come on down.” Sandy and the others stopped at the first landing and looked back up. Casey peeked over the side, then the rest of them, led by Frank Sanchez, started down the stairs. They were all down and herded together with Bobby and Reuben, but the detective continued to look up the stairs. He switched the bullhorn on again, “All right. I said all of you. Now!!”

“We’re it,” Kenny said. “There’s nobody else up there.” The priest, a pudgy, solemn man of fifty, stood well away from everyone else, on the lawn. He stood with his arms folded precisely, above the swell of his stomach, and watched everything.

The detective jerked his head at two of the cops in sneakers and sweatshirts. “Garber. Swayne.” The two unsheathed their revolvers from the snap holsters on the back of their belts and crept up the stairs. As they neared the railing, they flattened close to the wall, and the leader edged up until his eyes were level with the parapet. The roof was flat and without obstruction. His head craned forward until he could see over the parapet and see there was no one hiding behind it. He straightened, stood, and then both of them bounded onto the roof, guns held out. They reappeared, leaning over the railing, “That’s all.” The detective turned and counted them in disbelief. “Eleven?” You’re starting a war with eleven of you? Jesus Christ. You’re out of your minds!”

“Sorry, Father,” he said. This was addressed to the thin, red-haired Brother beside the boys.

The red-haired Brother stared with bright eyed intensity at the boys. Some were embarrassed and their gazes dropped. “Casey, of course,” the Brother said. “Culver, Sanchez, I expected. But Wiley? What are you doing, Wiley? What are you doing, man?” The Brother’s face was reddening, and his voice had gone high, tight and tinny. His brogue was cutting. “And Martinez. Oh, that’s very fine. Martinez and Martinez.” He turned to the policeman beside him, “The president and vice-president of our junior class.” Ralph and John stood silently, two tall, clean-cut boys, their eyes and faces blank. “And the athletes, of course. Oh that’s very fine.” He stopped and looked them over, his black pupils wide with anger. “We will talk, gentlemen. We will discuss this in the future.” He spun on his sole and stalked away, a tall stick of a man, neck crimson, hands locked together behind his back, his arms a rigid V against his cassock and green sash. The priest watched him go and took out his pipe.

Kenny Culver, who had been looking around, dropped his gaze and nudged the boy beside him, Frank Sanchez. “Check the roof,” Kenny said. “I knew the bastard had to be here.” Sanchez looked at the roof of the main building, where a small man in a cassock studied them through binoculars. “Brother Cyril,” Sanchez said.

The school’s dean of discipline had apparently directed the operation; now, as they watched, Cyril beckoned to someone in the street beyond. They began loading the boys into the cars, a random operation. Wiley went by himself, into the front seat of the green sedan, with his hands handcuffed in back of him. Sandy Furillo was handcuffed. Roy and Casey were cuffed and the three were lowered into the back of a white sedan. The policemen supported them by an arm, guiding them in with a hand flat on their heads, to keep them from hitting the window frame. Bobby was cuffed, Reuben was not, and they went with the unfettered Martinez brothers in the back of the second white sedan. Kenny Culver, Frank Sanchez and Don Cherzniak were led to the last car. The two uniform officers fingered their cuffs and looked them over there. The driver said, “Any of you desperados going to make an escape on us?” He pronounced it “desper-ay-does.” Frank shook his head, Cherzniak shook his head, and Kenny said, “No sir.”

The cars backed and turned and rolled down the hill, in a convoy, heading for Eagle Rock Boulevard. On Eagle Rock Boulevard, every place they looked and down every side street, there were boys running—hurdling trash cans, crashing through hedges, hiding behind palm trees. “Look at all those guys,” Kenny said. “Did you see that?” Four young men in bulky car coats had burst out of a doorway after the police car had passed them. They broke through traffic and piled into a dangerously lowered copper-colored ’51 Chevy. “Those dudes aren’t from Hamilton,” Kenny said.

The policeman on the passenger side turned around. “You guys are damn lucky we showed up. You would’ve gotten massacred.”

Frank pulled on his chin hairs, his eyes narrowing into a slow blink. Cherzniak’s eyes were wide and startled, his mouth was open, and his tongue moved as he silently counted the running boys and men. A boy in a blue windbreaker skidded around a corner store, arms flailing, the taps on his heels scraping and throwing sparks. He fell, saw them, got up and sauntered into the store. In the lead car, Jim Wiley put his head down on the seat and cried, “I’m so ashamed. I’m so ashamed.” The detective tried to lift him, “Get up son. Don’t lie down.”

“I don’t want anyone to see me,” Wiley said.

They stopped for the light at York Boulevard, and the detective lifted him by the armpits and set him against the door. Wiley shook his head. His nose was running and tears were dripping from his chin. “I don’t want anyone to see me.”

The detective said, “You should’ve thought about that before.”

“Oh shit. Oh shit,” Wiley said, “my poor mother.”

As they neared the Highland Park Police Station, there was a small traffic jam, a double line of police and plainclothes cars, each stuffed with boys. There were five and six in some back seats, waving to friends in other cars, giving each other the finger, holding up handcuffed wrists, the hands clasped, shaking them like winners. The double line was squeezing into the station driveway, which was nearly blocked by a large black van. The faces of five or six boys periodically appeared in the grilled window at the back of the van. The van was rocking sideways, swaying on its springs from the impact of bodies, thumping from side to side.

There was a steady procession from the parking lot, policemen shepherding their charges up the steps and through the blocked open double doors. As they climbed out of the car, Cherzniak told Kenny and Frank, “I counted eighty-two and I missed some.”

“Most of those guys weren’t kids,” Kenny said. “Some of those dudes were nineteen or twenty.”

They were tramping up the stairs. A uniform officer held them up as they reached the top, “This all of the Catholic contingent?”

“Bring them in here.” He ushered them into an anteroom. “I don’t want them going in there wearing their colors.” The boys looked at him, mystified. “Get your jackets off!” Handcuffs were unlocked, jackets shed. A plainclothesman stuck his head in and looked at them. “Bright boys,” he said. There was a scuffling noise, and someone banged against the wall outside. They could hear the plainclothesman talking to someone in the corridor, “Did you see some of those guys? Half of White Fence was out there. So were the Flats, and the Avenues. Uncles, brothers, cousins, granddaddies. You laugh; there was a guy out there with a cane. You take on Shaky Town, you get all three generations. And all we caught were the babies.” There was laughter in the corridor. The plainclothesman stuck his head back in and told the uniform officer, “Ready when you are,” and then looked directly at the St. Patrick’s boys closest to him, Frank and Kenny. “You guys don’t know nothing about it, do you?”

The St. Patrick’s boys were led back to the corridor and became part of the knot of bodies jostling toward the roll-call room. Inside, a freckled man in a white shirt and a thin tie leaned on a lectern, watching them come through the doorway. He was clean-featured, just starting to bald. The plaque pinned to his shirt said: Captain Costello. A uniform officer came in from a doorway at the back of the room. “We’re full up in here,” he told the captain. The captain straightened, pushing up from the lectern. “Okay. Start filling in the rows here.” The St. Patrick’s boys were passing through the doorway now. The large room they were entering was walled, with lockers on three sides. Rows of long benches sat behind rows of bench-like tables. The tables had slanted tops, like school desks. Fifty or sixty boys were already seated—talking, laughing, combing their hair, checking out the newcomers. The St. Patrick’s boys were dispersed throughout the room. Bobby, Reuben and Casey were directed to the front row. Sandy Furillo, Don Cherzniak, Ray Flynn and Frank Sanchez sat in the third row. Jim Wylie, pale and distressed, was sent to the back. The Martinez brothers followed him, and Kenny Culver was sent to an empty place in the middle of a row, about halfway back. Kenny sat down. The boy on his right was dressed in an oversize blue work shirt, stiff and glazed from starch and careful ironing, and pleated, baggy black dress slacks. The shirt was buttoned at the cuffs and neck and the scalloped tails draped over the pockets of the pants. He was pulling matches from a book and arranging them in a circular pattern, red heads in, on the table. The boy on Kenny’s left wore a fuzzy green Sir Guy shirt with a slit pocket and thick, pearlescent green buttons that gleamed discreetly. The nap of the shirt was like mohair and looked as if it had been brushed. It was buttoned to the top, and his thin neck and arms looked frail in the rolled collar and wide half-sleeves. The cuffs of his starched khakis were cut and rolled down. The glassy tips of his Shriner French-toed shoes showed beneath the bell of the khaki bottoms. He was buffing the shoe tips with a folded bandanna. After Kenny sat down, the boy looked up. An imposing pompadour swept up from his small forehead. “Hey,” the boy told Kenny. “So howseet going?”

“All right,” Kenny said. The boy in back of him was drumming on the tabletop, eyes closed, head jogging. Two rows in front, a boy with a shaved head, wearing an army shirt, was bent low over the table. Within the sheltering crook of his left arm, he was industriously carving, digging into the wood with a small white pushbutton knife. Finished, he swept the chips and splinters to the floor and nudged his seatmate. “Check it out.”

The noise level of the room was rising as the police gathered around Captain Costello to confer. Emboldened by this lack of attention, boys stood to yell across the room to friends: “Jesse. Hey, homeboy.” “Pinche Pete. Que paso?” “Jesse. Over here, dude.” “Nada, man. Still hanging.”

Captain Costello broke from the group and returned to the lectern. “Okay,” he yelled, “let’s settle down.” In the comparative quiet that followed, clipboards were passed out to each row. Pencils were attached by strings to the spring clasps and a pad of lined paper was on each board. “You’re going to pass these boards down the row,” Captain Costello said, “When it reaches you, write down your name, address and phone number.”

“What if you don’t got a phone?”

“If you don’t have a phone, write down a neighbor’s phone.”

“Yeah? What if you don’t know it?”

“Write down your neighbor’s name. We’ll look it up.”

Another voice called, “Hey. What if you don’t like each other?”

“Hey,” the Captain responded with irritated mimicry. “That’s your problem. We need a phone number. If we cannot locate a parent, or responsible relative who will come collect you, then you will sit here.”

“Shit. My old man won’t come down.”

“That’s enough.”

“I’m going to be here all night. That’s bullshit.”

“What’s your name?”

“Gil.”

“What?”

“Gilbert Reyes. Gilberto. Gil. No, use my real name, El Vato Loco.” The boy who spoke was the drummer behind Kenny.

“I’ll remember you Gilbert,” the Captain said. “Now shut up.”

Gilbert grinned at the boys around him. When Captain Costello looked down at the papers on the lectern, Gilbert told them, “He don’t scare me.”

The Captain spoke in a reasonable sing-song, “Shut up Gilbert. Or you get to sit against the lockers.” The Captain did not look up. Gilbert grinned again, his eyebrows shifting and his eyes rolling to show his continued courage.

The clipboards crossed the rows. “Print,” Captain Costello said. Someone called out, “You want like the last name first and the first name last and that jive?”

“Just write your name, the way you always do. And be sure to print.”

When the clipboards returned to the aisle, policemen picked them up and transferred the names, phone numbers and addresses from the pads to large index cards. These cards were taken to the Captain and he began to call out names, check the information and ask for more. “Felix Cruz. What’s your mother’s name, Felix?”

“Linda.”

“Your dad?”

“Ernie.”

“Age?”

“My age?”

“Your age.”

“Fifteen.”

“Any nicknames or gang names?”

Felix thought a moment. “El Gato?”

“The Cat? Felix the Cat. Great.” The Captain wrote it down. “Sandy Furillo. Where’s Furillo? How old are you Sandy? Any gang names or nicknames?”

Sandy thought it over, “The Eagle.” Cherzniak reacted with a violent start, jerking his head back to stare at Sandy. “I always liked that name,” Sandy told him.

“Don Cherzniak.”

“Seventeen.”

“Any names?”

“Nah.”

“Wait, wait,” Sandy said. “Yeah you do. Banana.”

“What?” the Captain said.

“He eats a lot of bananas. He’s known for it.”

“Oh yeah,” Cherzniak said, “Banana.”

Nearly everyone had nicknames after that. Kenny Culver pointed to a large raised patch of keloid tissue on his elbow, the result of a childhood burn. “They call me Scar-Arm,” Kenny said. Sandy and the other St. Patrick’s boys started laughing.

“Scar arm?” Captain Costello said doubtfully.

“Yeah!”

The boy with the pompadour reached out and fingered the scar, “That’s really cool. Where’d you get that?”

Kenny looked around them and whispered, “I can’t talk about it with cops around.”

“Henrique Gomez?”

“Yeah.”

“Age?”

“Fourteen.”

“Nicknames?”

“Chili Henry.”

The boy who’d carved the message on the desk called out, “Tell him your other name.”

“Shut up,” Chili Henry said.

“It’s Maricón.”

“Shut up.”

“Maricon?” Captain Costello said. “You mean like fairy?”

The carver called out, “The dude’s from Mexico, man. First day of school, they ask him who he is and all he says is, ‘I American. I American.'”

Chili Henry turned all the way around, “I’m going to cut your huevos off.”

The boy to Kenny’s right was rearranging his matches in a spiral pattern. The boy with the pompadour nudged Kenny. “That guy, there,” he said. Kenny pointed his head toward the boy with the matches, said, “That guy?”

“Yeah,” said the boy with the pompadour. “He’s been busted three times for arson.”

“Arson?” Kenny said.

“Yeah. He rides along on his bike and throws matches into cars that gots their windows rolled down. He burned three of them on his own street. To the ground. To the ground!”

“Pete Madrid,” the Captain called out. “Where’s Pete Madrid?” The boy with the pompadour leaned across Kenny to talk to the boy with the matches, “Pedro. Hey, they’re calling you.”

Pedro looked up. “Oh yeah. I forgot. Hey,” he said, and raised his hand. “That’s me.”

“Any nicknames?”

“Uhm. Pedro?”

“Do I know you from someplace?” The Captain stared at him.

“I don’t know,” Pedro said. “Maybe.”

“Where?”

“Como?” Pedro said. “Where, what?”

“Where do I know you from, Pedro?”

“Maybe you busted me once. I don’t know.” Pedro leaned back, latched his hands behind his head and grinned.

“Pedro Madrid. Pedro Madrid.”

The Captain repeated until the name fell into place. He snapped his fingers and pointed. “Bicycle Boy. You like fires, don’t you?” Pedro shrugged and continued to grin. The boy with the pompadour was nudging Kenny again. “Hey, you want to see something? Dig this.” The boy raised his left foot and rested the ankle on his knee. He lifted the slit cuff of his khakis until his sock showed. There was a lump in the sock. He peeled it down to expose the curved pearl handle and chrome hammer of a derringer. Kenny stared. “Is it loaded?”

“Fucking aye,” the boy said. He tugged the sock up and put his foot on the floor. Kenny nodded, impressed. “You ever shoot it?” he whispered.

“Yeah. It don’t shoot too straight. You got to be pretty close to hit something.”

“What’s your name?” Kenny said.

“Freddy.”

There was a commotion behind them. Gilbert Reyes, the drummer, had jumped to his feet and was threatening the boy behind him. The boy had apparently hit Gilbert in the neck with a pencil; he was still retrieving it when Gilbert turned around, Gilbert saw him pulling it back by the string.

“What’s going on?” Captain Costello said.

Gilbert jerked a thumb, “This cabrón has got to play. He hit me in the back.” “Reyes,” the Captain said, “I told you once before to shut up.”

“I didn’t do nothing,” Gilbert said. “It was all this puto.”

“No tengo miedo,” the other boy said. “Besamé culo.”

“That’s it, Reyes,” the Captain said. “Go sit by the wall.”

“I didn’t do nothing.” Gilbert’s voice swelled with innocence and injury.

“Move!” Captain Costello pointed to the wall of lockers.

Gilbert shrugged and ambled toward the lockers. “I never do nothing. Trouble just follows me around.” He sat down on the floor, his back to the lockers.

“Face the lockers. I don’t want to see your face.” Gilbert sighed noisily and scooted around. He turned back to give the finger to the boy with the pencil and say, “Fucker. I’ll take care of you at home.”

“Wylie,” the Captain called. “Where’s James Wylie?” Jim Wylie lifted his pale, pinched face and slowly raised his hand. “Wylie,” Captain Costello said. “How come you didn’t put down any address or phone number?”

“I don’t live at home. I live by myself.”

“What’s the address?”

“I just moved. I don’t know.”

“Right,” the Captain said. “Right. Okay. What’s your father’s name, Wylie?”

“He’s dead.”

“What’s your mother’s name?”

Wylie’s head dropped so they could no longer see his face.

“I haven’t got time to play with you Wylie. If I have to, I’ll call the school.” Wylie shook his head. Captain Costello crooked his finger at one of the plainclothes cops in the doorway. He handed him Wylie’s card—”Call the school. Ask for Brother Cyril.” The Captain read another name: “Anthony Villareal. Where’s Anthony?”

Gilbert Reyes was twisting a bobby pin in the lock in front of his face. His head rested against the louvers in the locker door and he was concentrating so hard on the lock that he didn’t see the policeman approaching. The policeman snatched him upright by his collar and Gilbert faced Captain Costello with the bobby pin still in his hand.

“That’s it,” Costello said. “Cuff him.” The policeman pulled Gilbert’s wrists together behind his back, clicked the handcuffs shut and lowered him to face the lockers again. Gilbert arched, twisted his head sideways and looked down, past his ribs, at the handcuffs and his waggling fingers. He craned the other way to squint open-mouthed at Captain Costello, and after a moment Gilbert addressed him. “Can I talk to my probation officer?”

The names had all been called. The cards were passed to a sergeant and the sergeant went out. Captain Costello went back behind the lectern. He grasped it at the sides and rocked a little, looking at them until they settled down. “Your parents are being called. You’ll be released when someone comes to get you.” There was a burst of noise, congratulatory and relieved talk and laughter. The Captain’s face reddened as he shouted at them. “Shut up!” The room quieted. “We will keep your names on file. If you are ever picked up for anything else, this will count against you.” Again the room swelled with noise. Pedro Madrid threw a match at Chili Henry’s neck and told him, “See, Baby, I told you they couldn’t bust us. What a cherry.”

This time the Captain waited them out. The noise descended to an anticipatory buzz. His cheeks and the tops of his ears were still flushed. “Nothing happened,” Captain Costello said. “So let me tell you what could have happened….

“You could have been shot. You could have been stabbed. You could have had your teeth broken by a pipe. You could have had an eye whipped out by an aerial. You could have been killed. I’ve been on gang detail for twelve years. I’ve seen all those things.” The room continued to buzz, and the Captain raised his voice. “It didn’t happen this time. It could have. Don’t trust your luck.” Gilbert Reyes, still facing the lockers, made two loud kissing noises. That side of the room began to laugh. The Captain slowly closed his eyes and shook his head. Freddy told Kenny Culver, “Oh man. That guy’s full a shit.”

“Yeah,” Kenny said, “Cops are always full a shit.”

It took a long time for the room to empty. The first set of parents showed in half an hour. There was a gap of ten minutes and then, boys were called out regularly. The boys who remained did not get to view the transfers; the parents were taken to a room near the top of the stairs and the boys were brought to them. Most of the exchanges were quiet. Sometimes there was yelling, weeping; once it sounded like someone rolled down the stairs, and once, the boys were entertained by a female voice screaming abuse at the policemen.

Captain Costello had left the room, returning only to inform Jim Wylie that they had reached his mother, and she preferred that they keep him overnight, so he’d learn his lesson. Bright spots of color appeared on Wylie’s cheeks, but his features remained determinedly stony. The four uniformed policeman monitoring the room kept it in good order. Gilbert Reyes had been removed. They were allowed to talk, quietly, but as the hours passed and spaces along the benches increased, boredom and anxiety dampened the conversations. Only one parent made it as far as the roll-call room. Frank Sanchez’s father, a small man in overalls and a hardhat, his clothes and shoes spotted with tar, pushed through, calling for his son. Frank reached the doorway as his father came in, clutched by two plainclothesmen, who released him there. Frank’s father embraced him fiercely, and then stared over Frank’s shoulder angrily, his eyes sweeping the room and the remaining boys. Kenny Culver was the last St. Patrick’s boy to be called out. He waved goodbye to Jim Wylie and followed the sergeant. His older brother, Tom, a recent high school graduate, was waiting at the desk. Tom laughed at the sight of him, “Fucking Kenny.”

The plainclothesman who had ragged them on the way in was standing there, leaning against the desk and laughing at something he was hearing on the phone. “Can’t believe what they say on these 800 numbers. It’s like a two-minute honeymoon,” he said. He cupped his hand over the receiver, pointed at Tom and told the sergeant, “You had better check.” The sergeant went to see if Tom was old enough to be considered a responsible relative. The plainclothesman watched them, listened to the phone and rasped his palm back and forth against the stubble on his cheek. Kenny whispered to Tom, “Where’s Mother?” Tom shook his head and looked away from the plainclothesman.

Just in back of them, the swing doors leading out broke slightly, joined, and broke again, sucked and released by a draft from the stairway below. The plainclothesman hung up the phone and put his palm on his stomach. “You guys still don’t know nothing about it, do you?” The sergeant came back. He had Kenny’s school jacket with him. They signed the release and Kenny was given his jacket. The sergeant held open a swing door and pointed to the stairs. They stopped on the landing so Kenny could put on his jacket. They heard the plainclothesman talking to the sergeant. “Good Catholic boys,” the plainclothesman said. “Good and dumb. They’re lucky to be alive.” Kenny whipped around and thrust his fist and upraised finger towards the doors. They clattered down the stairs and went out. It was still light outside. “Where’s Mother?” Kenny said.

“She was still at the teachers’ meeting when they called,” Tom said. “I got the Harrises to drive me down.” Mr. and Mrs. Harris were their neighbors, a pleasant couple in their sixties.

“So Mother doesn’t know?” Kenny asked.

“Nope.”

“Great!” Kenny’s heart lifted. He had a quick flash on the first moment that day, when his heart had dropped, as the rank of Brothers in their black cassocks and wide green sashes had wheeled around the corner of the school building. It brought him down a little, and then he steadied. It was Saturday. There was still Sunday. The complications and consequences were deferred one day, and for Kenny that was reason enough not to think about them at all.

They went out the gate and once on the sidewalk, off police property, their gait changed to street bop—chins up and pointing, shoulders back, elbows out. Their fingertips were tucked in the front pockets of their jeans. Their hips remained locked. Their knees lifted and broke with each sliding pop and stride. Their shoulders rolled side to side like sailors’. The Harrises’ car was on a side street and they angled that way without once breaking step, making minute adjustments, the necessary slides and skips, without checking. They wheeled around the corner, their knees bobbing together in elaborate cadence. Kenny smiled without looking at his brother, enjoying the feel of the walk, the way they must look to watchers.

A green Mustang on the opposite side of the street wheeled out of a parking place and idled forward. The back window of the Mustang cranked halfway down. There was movement in the shadowed back seat. The snout of a shotgun edged out over the glass. The twin barrels lowered to rest on the glass and probed forward uncertainly, like a mole sniffing the air. The Mustang glided into the wrong lane as it closed on the two white boys on the sidewalk, the shotgun barrels steadied and swiveled, tracking. Then stopped, and kicked up, once and again with the blast of each barrel.