The RV barreled down the 40 East towards Flagstaff at 70 mph. Chidinma’s father had rented it a day ago and had spent close to an hour disinfecting it, the leather seats, the wide windows. “You never know who has been in these things,” he had said as he shined the table. “Lepers, dogs with worms.” Chidinma had wondered why a leper would need an RV. But she had said nothing to her father. Now, a day later, the RV was an hour into an eight-hour drive from Los Angeles to the Grand Canyon.

Chidinma’s aunt, Agnes, and her cousin, Tobechi, were wide-eyed, marveling at all the space, at the Mojave Desert stretching for miles on both sides of the moving vehicle. Her three brothers, Soluchi, Chiefo and Chike, were seated at the booth on the opposite side, taking turns on the Nintendo Switch. In front, her mother sat in the passenger seat and her father behind the wheel. Chidinma felt suffocated.

When the RV stopped in Needles, near the California-Nevada border, Chidinma rushed out of the vehicle. The whole family had pancakes at a roadside diner. Aunty Agnes took out her cellphone and snapped pictures, taking selfies with random objects, a worn sign, an overflowing trash can.

Back in the RV, however, and Chidinma had had enough of their oohs and aahs. She was tired of her aunt proclaiming every few minutes that God was good, tired of her cousin, Tobechi, sitting with his face pressed against the RV’s windows, his breath forming shapes against the glass. Chidinma had brought along three books. But she found that her head hurt when she tried to read them. So she focused her eyes, instead, on the shape of her father’s head in the driver’s seat, her mother handing him trail mix from the large bag they had bought at the grocery store.

As they neared the Grand Canyon’s south rim after nearly seven and a half hours of driving, Aunty Agnes opened her mouth and a shrill cry came out, not unlike that of a dying animal. Agnes began a raucous song about favor and blessings. Her voice was high pitched, and it reminded Chidinma of the voices of the women at church, nasal and unbearable. Chidinma wanted to cover her ears. The tears in her aunt’s eyes, dripping down her cheeks as she sang, filled Chidinma with a strange rage.

Aunty Agnes and Tobechi had arrived in America from Nigeria just six months ago, carrying all their earthly belongings in three suitcases, their worn clothes and battered shoes. They were running from their crazy husband and father. Chidinma did not know the full details of her aunt’s plight; she only knew that her aunt’s husband was violent and mentally disturbed. The saga had been at the center of her parents’ arguments for the nearly ten years it had taken her father to bring his sister to Los Angeles from Lagos. Chidinma’s father was on a crusade to save his younger sister, his only sibling. And though Chidinma’s mother was sympathetic, she was worried that Agnes, who had never worked, would become a burden on the family.

Chidinma could still remember the first time she became aware of her father’s crusade. It was six years ago, when she was six, and her father was seated on the sofa in their living room, his head buried in his palms. Aunty Agnes was in the hospital, near death after her husband had beaten her. Chidinma could not understand exactly what was happening, but she could hear her father’s despair. It was strange to her because she had never seen her father so upset. Sadness was an emotion he seldom allowed anyone in the family to display, saying it showed a lack of gratitude for the way the Lord had blessed the family. So watching her father sob into his hands had left an impression on Chidinma.

The night she had finally arrived in America, Aunty Agnes had thrown herself into her brother’s arms. Chidinma’s father had smiled the biggest smile she had ever seen on his face, showing off immaculate teeth. “We will give you a new life here,” he had said.

◆

Now, they were on their way to the Grand Canyon. This trip was to introduce Aunty Agnes to America and especially to the western United States, land of cowboys and yurts and deserts and sprawling cities. It was a part of the country that held a certain mythological cachet in the Agu family. For years, the lure of the West had preoccupied her father. Chidinma’s father had first arrived in America from Nigeria a penniless student in 1984. He had settled in frigid Minnesota where Chidinma was born, but for years all he really wanted was to be out West, in Nevada or Arizona or California. After years of planning and plotting, he was finally able to move the family from Minneapolis to Southern California in 2012.

Chidinma’s father had grown up in Nigeria watching westerns, John Wayne crisscrossing sandy deserts on horseback. He could recite huge chunks of dialogue from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Stagecoach, High Noon. Chidinma’s earliest memories were of watching Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly on her father’s lap, listening to him hoot and holler in excitement.

Her father’s idea of the American West was thus still of outlaws and gun slinging sheriffs, dusty saloons and vigilante justice. He owned seventeen pairs of cowboy boots, nine belt buckles, six pairs of boot spurs, and a revolver. The revolver was encased in glass and hung over the mantel in the family living room. Years ago, her mother had begged him to take it down. “I don’t want my children to grow up around guns,” said her mother, whose father had been shot to death in front of her during a robbery in Enugu. But Chidinma’s father had moved it to the den instead and placed it in a corner, out of sight but not out of reach.

Every year, Chidinma’s father also flew to Las Vegas for the National Finals Rodeo. He prepared for these trips by shining his boots and starching his shirts. Days before the trips and her father would dance around the house in his shined boots, drinking bourbon. Once, Chidinma had caught her father on television at the rodeo, waving into the camera. He did not look out of place, not with his cowboy hat and pressed shirt, his eyeglasses gleaming in the stadium lights.

◆

It was now hot in the RV and her father was singing along to an old country song. Aunty Agnes was fiddling with her cellphone, murmuring prayers under her breath. The twins had switched to playing WHOT. Outside, a sign indicated that they were thirty miles away from their destination. Chidinma fanned herself with her hands.

Chidinma’s oldest brother, Soluchi, peered over her shoulder.

“What are you reading?” he said. At fifteen, Soluchi was already nearing six feet, muscles rippling from his neck. He was wearing blue jeans and a Washington Redskins shirt their father had bought on a work trip to DC.

“None of your business,” Chidinma said.

Their father stopped singing, listening to the exchange. Chidinma could see him peering at her from the rearview mirror.

“Look at your sister,” he shouted at Soluchi. “She always has her head in a book. Not playing around like she doesn’t want a bright future.”

When their father became distracted by the road again, Chike, one of the twins, knocked the book out of Chidinma’s hands. It fell to the floor.

“Goody two shoes,” Chiefo, the other twin said.

“Suck up,” Chike said. They too wore matching Dallas Cowboys shirts. Her father had thought it clever to pair the two shirts, Cowboys and Indians, and the boys thought it funny to always wear them in tandem.

Chidinma stuck her tongue out at her brothers. She tried to pick up her book but Soluchi had kicked it hard across the floor. It was her cousin, Tobechi, who bent over and picked up the book. He dusted its covers. Then he handed it to Chidinma. He said something, but Chidinma did not catch what he said, and she did not ask him to repeat himself.

◆

When they finally arrived at the RV park, it was late afternoon. The sun’s rays were still merciless and Chidinma felt its violence on her skin. Her father eased the RV into a small parking space between two other RVs. He shut the engine, clapped his hands.

Outside, families milled about. Some were barbecuing on portable grills, others were lounging in lawn chairs. The RV park was large, thin trees and dead grass. It was filled with vehicles, white and gray and silver RVs, campers, trucks. Several children ran between cars, throwing a football.

Chidinma’s brothers began to jostle each other like brothers did. Soluchi corralled the twins into a short-lived game kicking rocks in each other’s directions. But when their father climbed down from the RV, the boys stopped, fearing that he would give them a tongue lashing for misbehaving in front of white people.

When he said such things, her mother would launch into a lecture aimed at no one in particular about how America was not really our country, so it did not matter how people saw us. But if America wasn’t our country, Chidinma always wondered, then whose was it? They had been born here, raised here. All they knew was here.

As the sun set over the RV park, her father busied himself with connecting the RV to the park’s amenities, running water and electricity. He hummed under his breath and Chidinma could see how happy he was. She saw her father’s delight, his excitement at being out in the wilderness, doing something he felt brought him closer to his cowboy heroes.

An hour later, with the RV all connected and then meticulously cleaned again, they began the mile-long journey to the first vista point, kicking up dust as they went. Aunty Agnes sang the whole way. Her wig, old and matted, obscured much of her face. Nevertheless, Chidinma could still see the tears in her aunt’s eyes. She wondered if Aunty Agnes would keep crying for the rest of her life.

Aunty Agnes sang about God’s glory, about his ability to deliver his disciples from the jaws of Satan. She pointed at the valley in the distance and then at the sky. “Come and see American wonder,” she sang.

Tobechi followed closely behind his mother. His hands were jammed into his pant pockets. In the six months since they had arrived from Lagos, Chidinma had hardly heard her cousin’s voice. And when she did, it was that familiar murmur, an inaudible question directed always at her. Tobechi seemed comfortable around her, which naturally made Chidinma uncomfortable, so much so that she walked away whenever she heard one of his muffled questions, whenever he tried to talk to her. Lately, he had begun to avoid them, her and her brothers, and stuck closely to his mother.

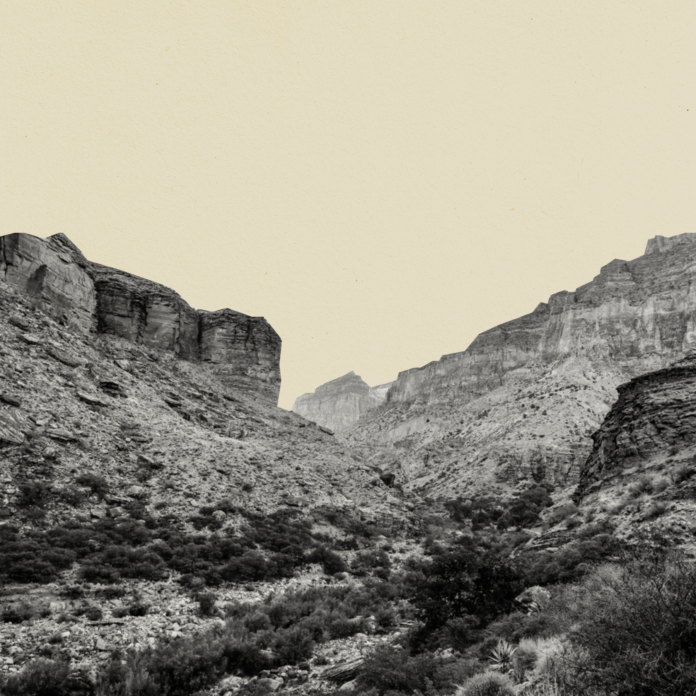

At the vista point, they stared in amazement at the magnificence before them, the sky, pink-purple over their heads. The gully was deep and wide, surrounded by jagged, red rock. They stood at the very edge of the cliff, nothing separating them from the depths below. Down in the curve of rock and sediment, the Colorado River snaked through, green and luminous. Birds criss-crossed the open sky and settled on the desert trees, watching the tourists with muted concentration, as though the birds were assassins, killers stalking their prey.

It was still hot and Chidinma’s father was wearing the same pressed shirt and jeans he wore to the rodeos. He had also put on his white cowboy hat and studded boots, and he strutted the 20 yards from one end of the vista point to the other, his thumbs hooked into his belt loops.

Her brothers were shielding their faces from the sun with their hands. They bounced on the balls of their feet, already bored with the scenery. But Chidinma found the expanse breathtaking and looking at her cousin, Tobechi, she saw that he too was enthralled by the landscape. His small mouth was open in a silent “O,” his hands limp at his sides.

Chidinma was thirsty. She went over to her mother who was holding a bottle of water, watching the scenery with Aunty Agnes, feigning interest as Agnes described a vision she had received three years ago in which she was standing in this exact spot. The look on her mother’s face, a sour look, her lips pursed, let Chidinma know that her mother was in one of her irritable moods. So Chidinma returned to the edge of the cliff where she peered into the depths below, her head spinning at the distance between her and the very bottom of the canyon.

After many minutes of strutting, Chidinma’s father announced that it was time for pictures. He began to pose, one hand on his hip. Her mother joined him, then Aunty Agnes, then the boys, then Tobechi, reluctantly. Chidinma clicked away on the digital camera, capturing a variety of angles, the sky as a backdrop in one photo, the starving trees in another. When it was time to take one with the whole family, her father asked a white man wearing sandals and a Hawaiian shirt to do the honor.

Chidinma’s brothers threw rocks in the direction of the Canyon to see how far they could go. Tobechi watched them but did not join. His mother burst into fresh tears. After a series of loud wails that made other tourists turn to them, Aunty Agnes gave her brother another long hug, tears dripping down her face.

“Thank you,” she murmured between hiccups. “Thank you for fighting for me.”

Then she turned to Chidinma’s mother, who smiled one of her fake smiles, her face pinched up, lips folded. It was her white people smile, the smile she gave the receptionist at the pediatrician’s office when he asked her to repeat her name because he couldn’t understand her accent.

◆

Chidinma knew her mother was trying. Her mother took Aunty Agnes to the grocery store with her, to the women’s meetings. But Aunty Agnes was a battered woman, Chidinma’s mother would tell her father when she didn’t think anyone else was within earshot. Aunty Agnes was afraid to use the stove because her husband had once held her face against it. She was afraid to ride in the car because her husband had once shoved her out of a moving one. And Tobechi? Chidinma’s mother was most worried about him. He seemed troubled, a boy who had seen such violence needed the type of special attention that they could not provide.

For years, Chidinma’s mother had insisted that it was best to keep Aunty Agnes in Nigeria, help her leave her husband, and provide her with financial support while she looked for some type of paying work.

“We have four children,” her mother had said. “Our oldest will soon go to university. How can we afford to take in your sister and her young son? Where will we find the money?”

But Chidinma’s father had shaken his head so violently it looked like it would fall from his neck.

“She’s my only sister,” he had said. “And I’m bringing her here. So find a way to make it work.”

And now, Chidinma’s mother was resentful. The burden of seeing to Aunty Agnes and Tobechi fell on her because Chidinma’s father worked hours away in a power plant in central California. He came home only on weekends and holidays, leaving the day to day running of the household to Chidinma’s mother. Thus, when Tobechi’s eighth grade teacher called a parent/teacher conference to discuss Tobechi’s reticence and refusal to participate in classroom activities, it was Chidinma’s mother who went to explain that he was new to the country, that he needed some time to adjust. She was the one who refused to put him in a special education class, a branding she said followed Black boys for life.

◆

One thing Chidinma had noticed about her cousin was that he ate very little. He hardly finished the rice and stew, the farina and ofe egusi that her mother put on his plate.

“That’s how he eats,” Aunty Agnes had said of her son. “He’s a good boy,” she had added, as though in apology. Chidinma had overheard her father scolding Tobechi for incurring detention and a parent/teacher conference so early in his American schooling.

“We did not bring you here to become useless,” her father had said to Tobechi.

But her mother had interjected.

“Don’t mind the idiots,” she had said of the school administration. “Detention for something so silly? They don’t do that to the white kids.”

Her father had insisted it was not a race thing.

“When they tell you to do something, you do it,” he had said.

But her mother had reminded him of the Black girl in some school in Denver who police had pinned to the ground for coming to school late.

“She was probably mouthing off,” her father had said.

It wasn’t that her father didn’t understand racism, Chidinma knew now. It was that he saw it as interpersonal rather than systemic, something that could be overcome by good behavior. And so when he came home from work one weekend with the word “nigger” sprawled in black paint across the body of his silver Honda, or when he was passed over for a promotion for a younger, less experienced coworker, or when he was pulled over and then manhandled by a Fresno cop, he had simply vowed to work harder, to give them no reason to single him out.

◆

They continued on to another vista point, the sun’s powerful rays setting over the expanse. Tobechi inched closer to Chidinma.

“I like to read too,” he said. It was the first complete sentence Chidinma had heard out of his mouth in days.

Chidinma did not look at him.

“What were you reading earlier?” he said.

Chidinma did not respond. Tobechi turned his face back to the rock and silt.

“I’ve started reading about Arizona,” Tobechi said, coming even closer to Chidinma. “Did you know that much of this land once belonged to the Havasupai?”

Chidinma nodded.

“Sure,” she said.

“Yes, they were violently pushed off this land of course,” Tobechi said. “But they are still here. Along with the Diné, and the Hualapai, and the Hopi.”

Chidinma turned to her cousin. He was rail thin, his angular face devastated by pockmarks and pimples. Her mother had given him a package of Proactiv, along with deodorant because his eighth grade teacher had told her he smelled. In a brief moment of closeness last week, he had confided in Chidinma that his classmates laughed when he spoke, that they kicked him during P.E class, threw the ball at his head, called him an African baboon. Chidinma had nodded as she did now, offering no words of comfort or encouragement.

“There’s a Diné boy in my class,” Tobechi said. This time he was louder and there was excitement in his squeaky voice. “He refuses to say the pledge of allegiance in the morning. Mrs. Presley has tried to make him do it. But he refuses. So one day, I refused to do it too. And that’s why they called your mother. That’s why they threatened to put me in a special education class.”

Chidinma’s father had lectured her and her three brothers countless times about getting involved in “anti-American movements.”

“Do you want to get arrested?” he had told them. “Do you want to end up dead or worse, in jail?”

So now, Chidinma felt a sense of awe and respect for her cousin. And fear too. For her father was lethal with his belt when he was angry. She imagined her father flogging her cousin, stretching his shirt taut, telling him that he would send him back to the village to shit in a pit toilet and bathe out in the open.

“If you’re bent on being useless,” she imagined her father saying. “Then you’ll be sent back to where you’ve come from.”

◆

Once, when Soluchi was thirteen, he had come home from the playground with his shirt torn, a bloody wound on his forehead. He’d been beaten up in a fight on the basketball court. That evening, their father was so angry that he threw his shoe at Soluchi’s head.

“It wasn’t my fault,” Soluchi said. “These dudes just jumped me out of nowhere.”

Her father didn’t believe him.

“Out of all the people on God’s green earth,” her father said. “They found you and jumped you?”

He retrieved his shoe from where it had landed on the sofa and grabbed Soluchi. He pinned Soluchi to the ground, beating him with the shoe until their mother intervened, calling their father a nonentity and an agboro.

“Leave my child alone,” her mother screamed. “You crazy bastard.”

But her father would not relent.

“I am God in this house,” he said.

Her parents were staunch Catholics. It was the one thing they both agreed on. And so Chidinma had been raised with prayer and the fear of eternal damnation. Each of the children had gone through the sacraments, baptism, holy communion. Soluchi was in the process of receiving his confirmation.

Yet her father called himself the one seated at the right hand of the father. “I am your God,” he would say to his children. “I am your alpha and omega. When you pray, you pray to me.” Her mother, who was always apt to challenge her father on such matters, kept mum.

But for days after the beating, their mother was distraught, accusing their father of being a tyrant with a God complex, no different from Agnes’s husband. Her father was so wounded by the comparison that he did not eat for two days.

“You dare compare me to that craze man?” he said on the third day. “Nwando, you’ve never said something so hurtful to me before.”

◆

When Chidinma went to confession, she often told the priest about her father’s blasphemy.

“He calls himself the son of man,” she said. “I know it’s wrong. But I’m too afraid to say anything.”

The priest had then told her the story of Joan of Arc, burned to death because of her crusade on behalf of Christ.

“When you’re a follower of Jesus,” he had said. “You’ll be faced with many trials and tribulations. You have to be brave enough to withstand them.”

Chidinma had told the priest that she didn’t want to be burned at the stake. He had told her that sometimes, that was the only way to get to heaven.

◆

Chidinma had decided at nine years old that she would save her whole family by becoming a saint. Her mother had given her a book of saints, Saint Anthony, Saint Mary, Saint Leo, Saint Agatha. She had read the book from cover to cover, reading about piousness, miracles, violent deaths. She had decided that she would be like Mother Theresa, who she had decided was her favorite saint because her mother had a framed picture of the Mother in the living room next to a picture of Jesus and his disciples. If she worked hard enough, she reasoned, she would make it to heaven and bring her family, including her father, along with her.

For a whole year, Chidinma prayed the rosary every week. She would climb out of bed at 6 o’clock in the morning, kneel at her bedside and will herself to reach God. She prayed for her father, for her mother and for her brothers, for Aunty Agnes in Nigeria with her crazy husband.

When she’d told her mother at ten years old that she was going to be a nun, her mother had choked on her soda.

“Why would you say such a thing?” her mother had coughed.

“I want to be a saint,” Chidinma had said. “That way, we will all go to heaven.”

“There’s no way my only daughter will join a convent,” her mother had said. “There are other ways to become a saint, dear.”

Her father had said the same thing.

“Do good deeds on earth and you’ll surely go to heaven.”

For months, Chidinma was wracked with anxiety. How else would her family get to heaven? If she could not save their souls, then who would? She had spent many sleepless nights imagining her mother and her father and her brothers and even Agnes burning in hell. And she had become almost fanatical about her faith.

◆

On the second night, the RV park was loud with the noises of families gathered to break bread. As they sat around the grill waiting for a dinner of hot dogs and hamburgers, her father turned up his Kenny Rogers playlist and sang the words as he worked the grill. Next to the RV, Tobechi sat beside Chidinma, drawing lines in the sand with a long stick. His ears jutted out from his head, his shoulders hunched. Across from them, Tobechi’s mother and Chidinma’s mother discussed various pastors from back home, which ones could work the most potent miracles, which ones had become seduced by money and fame. Her parents were obsessed with miracle workers, priests and pastors who could raise the sick from their deathbeds and make the barren bear fruit. As the mothers talked about Pastor This and Father That, their voices drifted over the grill to the children, snatches of conversation mixed with her father’s singing and the noise of the other occupants of the RV park.

Soluchi finished his first hot dog and asked for seconds. Their mother fished out a second hot dog from the grill, but their father warned Soluchi about becoming too greedy.

“It’s grotesque,” her father said.

Soluchi sat back down.

“Never mind,” he said.

Their mother gave him the hot dog anyway.

“Let the boy eat,” she said. “The way you go on and on, you’d think these children have killed someone.”

“America is the kind of place where children can easily lose their heads,” her father said.

Chidinma’s father had many contradictory opinions on America. On one hand it was the land of opportunity, a place that had elevated his personal standard of living. On the other hand, it was a Sodom and Gomorrah, a place where anything goes, where children one day woke up and murdered their own parents in their sleep. As she grew older, Chidinma would come to understand that her father feared so much, that he was driven by a discomfort so visceral that he sometimes walked the halls of her childhood home at night, putting things in order until he was convinced that the rug would not suddenly be pulled out from underneath him.

Chidinma was sitting against the RV, trying to read in the darkness. Her father was now singing along to a country track about life on a Texas ranch. All he listened to was country music, not Osadebe or Oliver de Coque or King Sunny Ade like his friends. He preferred old country music as well as newer artists like Garth Brooks and Keith Urban. He had a turntable at home and he collected an entire library of country music, men with crystal blue eyes on the album covers with titles like Honky Tonk Lady and Redneck Gospel.

After many minutes, Tobechi got up and pulled his chair closer to Chidinma.

In the dim light, Tobechi’s eyes were glowing.

“Does your father know that there are Black cowboys?” he said suddenly.

Chidinma did not look at him.

“I wonder what your father would say if I told him that he doesn’t have to be white to be a cowboy, ” Tobechi said.

Chidinma was irritated.

“And what’s it to you?” Chidinma asked defensively. She didn’t like the idea of some stranger coming in and pointing out that there were holes in the fabric of her life. Besides, what did Tobechi know?

Tobechi shrugged. He looked at his uncle, opened his mouth to say something, and then closed it without speaking.

◆

The next morning, after prayers in which Aunty Agnes spoke in tongues for nearly an hour, Chidinma’s mother declared that she was sick of sleeping in the RV.

They were all seated in their respective corners of the vehicle, Aunty Agnes breathing heavily, Bible in hand, when Chidinma’s mother stood up.

“I want a proper shower,” she said. “To sit down at a table like a human being.”

Her father looked at her, exasperated.

“You are supposed to enjoy the experience,” he said. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the majesty of this land.”

Her mother shook her head.

“I’m not like you,” she said. “I don’t see this dusty landscape as anything special.”

That afternoon, Chidinma’s mother found a hotel. Chidinma wanted to go with her. She too was tired of the desert, but she was afraid of what Tobechi would say, what he would think of her. Perhaps he would think she was running, that he had gotten under her skin. And Chidinma was the kind of girl who hated losing, especially to a boneheaded boy. So she said nothing and her mother took Aunty Agnes with her. They were going to spend most of their days praying and eating and sitting by the pool.

“Like human beings,” Chidinma’s mother said to her father as she climbed out of the RV in front of the hotel.

Chidinma’s parents often quarreled. And when they did, it was usually after a buildup, her mother enduring something and then exploding. They had spent three days and two nights camping in the RV. Her mother was rightfully restless. She was a nurse, used to being active on her feet. She had also never shared her father’s delight in the glory of the desert west and Chidinma could tell that her initial enthusiasm, seven days in nature, had worn off. She and Aunty Agnes left for the hotel and Chidinma’s father drove them back to the RV park, lecturing them about the greatness of the American landscape.

“When I’m dead,” he said seriously. “Bury me in this desert next to the cacti and rattlesnakes.”

◆

On the fourth day, Tobechi asked Chidinma if she wanted to walk to the vista points. Chidinma was sitting outside, pretending she was reading though she was watching her cousin from the corners of her eyes. For nearly twenty minutes, he had been walking in circles, talking loudly to himself. Chidinma had caught him talking to himself several times, murmuring gibberish. But now, he was having a full blown conversation with the thin air.

Tobechi stood in front of Chidinma.

“We could go watch the tail end of sunrise,” he said to his cousin.

“Maybe,” Chidinma said, still peering at her book. The hairs on her neck stood up. Something about her cousin unnerved her. Perhaps it was the distinct wildness in his eyes, the fact that he could see things that weren’t there, that he seemed to be in communion with invisible forces.

For days, Chidinma had been watching her cousin. Out of everyone in the family, he seemed the most out of place, a fish out of water. He was tall and lean, taller than even Soluchi, and he walked with his shoulders hunched and his head down. The rare times he spoke, he did so softly and deliberately, like he had been thinking up his answers for days. Chidinma’s mother had told her father that Tobechi scared her.

“He’s an odd one,” her father had said absentmindedly. “But it’s nothing a good flogging can’t fix.”

Now, Tobechi stood and waited, staring at Chidinma. Chidinma looked up into his face, at his dark, contemplative eyes. She sighed as though she was indulging him.

It was early morning. The sky was a beautiful blue, cloudless, stretching over their heads like an endless tablecloth.

At the first vista point, they stood, staring out into the expanse. Chidinma turned to her cousin. It was already hot and there were beads of sweat on his forehead. In his old t-shirt and loose shorts, his eyes staring into the distance, he looked younger than his thirteen years.

She wanted to ask Tobechi why he was so strange. But Tobechi caught her looking at him.

“Wanna see something?” he said. Before she could answer, he reached for his shirt and lifted it over his head. There was a scar snaking down his front. It was a ghastly scar, wide and deep, shimmering in the light.

“A proud scar,” he said, eying Chidinma. “I fought my father one day after he hit my mother. Threw him down the stairs.”

It was the first time Tobechi had mentioned his father, the reason he and his mother had fled Nigeria in the first place. Chidinma did not know what to say. Instinctively, she reached out and touched Tobechi’s scar. It prickled under her fingers.

“What was it like?” She asked finally. “Living with someone like that?”

“It was terrible,” Tobechi said. “Like living with a wild animal. He was unpredictable in his moods. He would hit me with the buckle on his belt. Once, he bashed my head against the wall. But sometimes I think I miss it. Isn’t that crazy? Maybe ‘miss it’ isn’t the right word. It was my routine for so long, tiptoeing around the house like a mouse being chased by a stealth cat. And now, I’m relieved but also a little lost.”

◆

That night, Tobechi’s scar danced around Chidinma’s mind so that the next morning, she woke early and followed her cousin out of the RV without question. But the two did not go far, not to the vista points. They sat instead on the lawn chairs next to the RV. Chidinma was still apprehensive around her cousin. But she also felt a certain comfort in their silence.

“I think your father,” Tobechi said suddenly, looking at Chidinma with those piercing eyes, “your father, like mine, has learned not to see himself when he looks into the mirror.”

Chidinma nodded as though she understood what her cousin was talking about.

After lunch, they left the RV Park once again to explore more of the Canyon, this time with what was left of their party. As they walked the trail leading to a vista point they had already visited, Chidinma’s father posed for pictures with his hands folded, his hands on his hips, his hands on his cowboy hat. It was the most expensive hat in his collection and Chidinma remembered her mother’s anger when she found out how much it had cost. Tobechi leaned into Chidinma and said “Your father is a real onye ocha wannabe, a fake white man.” He threw his head back and laughed. “We have to do something about it,” he whispered.

◆

Chidinma was afraid of what her cousin had suggested. “Maybe a ritual,” he had said. “Perhaps someone has cursed your father. We could ask the universe to break the spell. Do you believe in the powers of the universe?”

At church, Chidinma had learned about temptation, about the devil sneaking into one’s life when they least expect him. And, though Chidinma had abandoned her crusade to become a saint, she still felt that she wanted to be holy, to be chosen. The idea of praying to a foreign entity felt both blasphemous and dangerous. She was in uncharted territory, in a world of symbols and metaphors. Yet, Chidinma suddenly trusted Tobechi. The idea titillated her too, made her arms tingle with goosebumps. She wanted to be wild too, to see the unseen, to convene with the forgotten.

◆

As the last day grew closer, however, Chidinma started to get cold feet. She wondered if her cousin had become evil, altered permanently by the violence he had seen. Perhaps that was the reason he no longer believed in Jesus, the reason he was so confident in boldly declaring this to her. Tobechi clearly wanted to get a rise out of her. Which is why he had laughed at her when her eyes widened in disbelief.

“What do you believe in if you don’t believe in God?” Chidinma had asked her cousin, her heart thumping in her chest. She had turned in the direction of the RV as though their words would float through the stiff heat and reach her father’s ears. The flogging they would receive would be one for the books.

Tobechi had shrugged.

“I see something else,” he had said. “Something much more powerful.”

◆

Tobechi had spent nearly an hour explaining to Chidinma the powers of the cosmos. They were seated in the dirt at the entrance to the RV park, watching vehicles enter and exit, people walking in and out. Her father had mentioned that morning that the parking lots were already full.

“The sun rises every morning,” Tobechi had said to his cousin. “The rains fall, the wind blows, and we say that the universe has no power, that this power belongs to a higher being we can’t even see?”

Chidinma chewed her lip.

“Look at us,” he said. “My mother is a good woman, pious, prayerful. What kind of God allows terrible things to happen to people like her?”

“But he rescued her,” Chidinma retorted though she felt the heat of Tobechi’s stare.

“After ten years? You know how long my mother has been waiting?”

“What about you?” Chidinma asked. “How long have you been waiting?”

Tobechi smiled.

“I’ve been waiting since before I was born.”

◆

Their last night in the RV park, there was a chill. The wind blew across the village and sent hammocks flying. But there was also a thrill in the air. In the RV, Chidinma slept on the floor next to the twins, her back to the windows. Tobechi slept where his mother had once slept, on the raised sofa beneath the far right window. Chidinma could hear her father snoring loudly from the back. She heard Tobechi hiss. And then they were both up.

They climbed out of the RV quietly, their breaths mixing with the cool night.

“Which way should we go?” Chidinma whispered.

“Let’s follow the stars,” Tobechi said back.

With the flashlight on, they found their way through the RV park and out into the desert. Chidinma’s sneakers snagged on rock and roots as she hurried beside her cousin, their excitement in the air. The two walked for five minutes, keeping the RV park within their periphery. When they had walked for five more minutes, it suddenly felt right.

Tobechi was the first to strip off his clothes. He took off his sweater, a blue number Chidinma’s mother had bought him at Sears. Then he stripped to his underwear, shivering, his palms under his armpits.

“Now you go,” he said to Chidinma as he took off his underwear, his thin body silhouetted by night.

Chidinma hesitated but only for a second. She felt a rush of adrenaline as she pulled her shirt over her head. She had tucked away her mother’s Bible and hidden her rosary in her purse. If things went wrong, she knew where to find them.

Soon, they were both standing naked under the stars, their clothes in a pile. Tobechi pulled the lighter fluid from the corner where he had put his shoes. He doused their clothes in the fluid and lit the match.

The flames flew into the sky, flickering bright as they licked and consumed their clothes.Tobechi closed his eyes and knelt in front of the fire. Chidinma thought of the warm insides of a cave.

“Stars and planets,” Tobechi began. As Chidinma listened to her cousin, she saw fat tears rolling down his cheeks. She was overcome with emotion that brought her, too, to her knees. She closed her eyes and listened as her cousin sang his prayer. His voice deepened and vibrated in his chest.

The landscape was beginning to morph and mold, to become something else. Sweat dripped down Chidinma’s face. She was in a trance, the heat of the expanding fire burning into her skin. A shooting star pierced the night sky, shooting its light across. The ground beneath her gave way, and she was falling.