I only picked up because my mother never called me.

“Kopal, you’ve upset your sister,” she said.

“Don’t be stupid.” I told myself I meant to say silly. I could see the sun like a hole over the eastern edge of Koramangala, the streets already busy with people and vehicles and smells, sweat, diesel, the burnt milk scent from the tea cart stationed too close to the ashram’s entrance. “Are you okay?” I asked.

“Rupa told me you upset her.”

Across the road in a parked car, two little girls made faces at me. I stuck my tongue out and watched them recoil in terror. I wondered if they were sisters. I forced myself to say, “Rupa is dead, Amma.”

Amma refused to agree with me. I hung up. I did not like to think of Rupa, or her death, for I could not remember her without the tongue.

When we were very small our mother took us to England so she could care for a child that wasn’t us. We saw Amma only briefly in the morning when she forced us to bathe and dress, forced us into neatness. We ate our meals with a variety of staff kept on in the grand manor, our mother in another wing with the child she nannied. She slept there too. Sometimes we spent our nights crouched outside the little girl’s room listening to our mother tell her stories. If the door was ajar, I would look in at the shining pink face and think, demon, demon, demon, naming her, perhaps, or hoping a stray spirit might find and destroy her and free Amma from her inexplicable grip.

My mother’s most repeated story was the one of Kali, red-eyed Kali, full of rage, humbled by love. Kali was summoned to kill a demonic army. Her anger grew so enormous that even after she destroyed every demon she could not stop banishing all her feet touched. She stomped around and vanished trees, roads, rivers, people. The other gods asked Shiva to intervene. He turned himself to wood and prostrated himself. She stepped on him. He transformed back under her toes. Kali bit her tongue between her fangs, shamed, and her rampage ended.

Amma told this story hoping to cajole the little pink girl into behaving, but it never worked. She was a difficult child. Because our mother was paid to care for her, I understood that I must be good. My sister, two years older, became angry. She was too smart to disobey when our mother was around. She saved her torments for me. She judged me for submitting to our new clothing, our new language, our new religion. You look like a dirty doll, Rupa would say to me, undoing her own braids so violently strands of black hair gathered on the floor.

In times of truce, uneasy as it might be, we explored the house. It was damp, smoky, enormous with age. There were a thousand rooms left abandoned, furniture covered in gray sheets, mirrors gone green at the edges, dust so thick we left drawings in them. Bedrooms on bedrooms, like the one we slept in, transformed by disuse. I tried every sagging mattress. Rupa looked in every unlocked drawer.

It took us a long time to find the tongue.

We weren’t sure what else to call the long, red thing that took up the width of a mean little hallway at the top of the house. The tip did not move. The other end disappeared into gloom, a passageway so long we could not see the end of it. The texture gave it away, damp, faintly spotted, depressed in the middle. If it was a tongue, it was huge. But I don’t remember finding it monstrous. I was excited at the thought of keeping a secret with Rupa.

Rupa wanted to touch it. She was braver than me. She saw the tongue as a barrier. She stole a knife from the kitchen, a small knife, very sharp. She went first into the hallway. I held the back of her dress, full of excitement and dread.

I remember the clutch of blue cotton in my hand going red, above it, the new mouth of my sister’s body, everything that made her human gone. Torso, arms, head, every black hair, gone. The remaining half of my sister knelt, like her body had life to it still, then fell, dragging me with it, my grip turning into a lock without a key.

◆

“You’re sick, Kopal!” Sharon said.

Amma’s call had rattled me. It was Sharon’s last day. The story of the tongue fell from my mouth easily, like a story you tell to scare a child late at night. I was grateful to be smoking. It kept the nausea at bay.

“You’re siiiiick,” Sharon repeated, but she didn’t believe me. There was laughter inside her friendly, foreign mouth.

Our smoke joined the general pollution of the city, a haze alive with the last arms of the setting sun. We leant against the ashram’s cement walls, far from the entrance where beggars gathered for alms. I had guided us outside. It didn’t feel good to run interference for Sharon, but I had wanted her to lend me a cigarette. Smoking wasn’t permitted inside the ashram, at least not by instructors. Students could do what they liked, since they were paying to be there.

“Seriously, do you even have a sister?” Sharon asked.

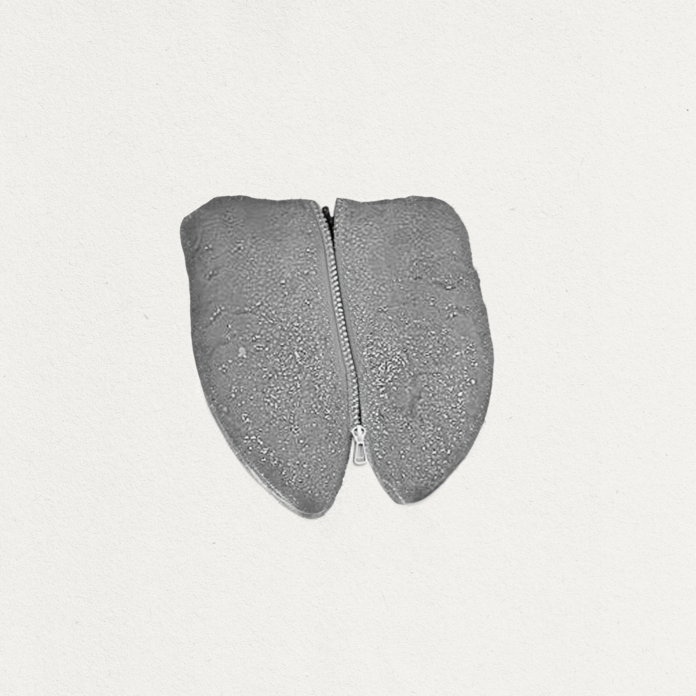

I blew smoke directly in her face, wondering if she would flinch. “I did this to honor her,” I said, sticking out my tongue, feeling the two halves against my lips. My split tongue, the mark of a freak.

The first recoil was slow to arrive, confused. White women, especially ones comfortable enough in the world to come to India on a yoga retreat, took a long time to alarm after they had decided I was safe. I was boyish and inoffensive, couching my directions as requests instead of commands during morning practice. But the tongue often did it. I flicked the two halves at Sharon. I studied her reaction.

“That doesn’t prove you have a sister,” Sharon said, studying me, trying to return us to a lighter tone. She looked away. She dropped her half-finished smoke. “Maybe I should go back inside?”

The maybe made me think she was angling for an invitation to stay, disturbed but fascinated. She had been flirting with me all week. I thought about transforming that look of pity and curiosity into pleasure, obliterating her questions about me. I hadn’t lost my taste for secrets.

“I can’t imagine there being two of you,” Sharon said, stepping closer.

Rupa and I had never been mistaken for twins. My interest cooled. I indicated I would stay to finish my cigarette. She faltered. I could see her confusion. She was calculating the differences between us, weighing my bad skin and shapeless clothing against her whiteness, her class. She wasn’t going to take my no. I suddenly couldn’t stand the thought of her tongue in my mouth. “Next visit, you can meet my husband,” I said, the lie as sweet and metallic as condensed milk. It worked. Sharon went inside without me.

When it was my turn to go inside, long after it was dark, I picked up the flattened butt she had left, hating to leave trash behind in this dirty, dirty city.

◆

The dream visits whenever it likes.

I stay with Rupa’s body, what’s left of it. I watch her blood go tacky with time, coagulating even though it won’t save her. I stare at my hand, dark against the cloth, now red. No one comes to look for us except Amma. When she finds us, she loses her mind. I try to tell her what happened but my tongue is a piece of wood in my mouth, the useless English word emerging, the Tamil word for tongue long gone from mine. Amma backhands me. I am collateral in her desire to look at what will destroy her. She screams.

When I wake with my mother’s scream at least the nightmare ends and I can sleep again. But sometimes our mother doesn’t find us. I spend the night alone with Rupa’s body and when I wake, I don’t know where I am. I put my foot down. My toes touch damp muscle. I am petrified. I fall to the ground with my limbs in a cool vice. Something touches my skin. I watch as I am sawed in two. Sometimes the cut is across my neck, sometimes it is across my waist. When it’s over I look at the part of me I’ve left behind. I am hollow inside. Rupa is suddenly there, picking up what is left of me.

I realize I am in a cave the shape of a mouth, I am behind the wall of the house that stole half of my sister, I am alone. I see her on the other side, fitting herself to my body. She turns to me and says—

◆

“I don’t want to hear about your nightmares,” my mother said.

The pongol sat cold in its stainless steel dish. My cousins had left us alone to talk, but my mother wouldn’t speak, and anger had turned me cruel. Since her call I had dreamt of Rupa every night. Maybe my dreams would stop if I told my mother about them.

My mother glared at me. She lived in the small guest room of my cousins’ house in the suburbs of Chennai, not her blood relatives, but my father’s family. I ensured this with a cut of my paycheck. It was cursory care and we both knew it, and that, maybe more than the past, lingered between us. She was a shrunken version of the woman I remembered, her eyes still lined in black but heavy with wrinkles. Someone had braided her thick gray hair and arranged her sari to show her long thali, perhaps for my visit. Angry, she looked alive for the first time since I had arrived.

“Don’t talk about Rupa,” my mother commanded.

“If you don’t want to hear about her, stop insisting she’s alive,” I said.

Amma’s eyes fastened on my mouth. Her hand shot out to grab my chin, grip so tight it felt like she was moving fat and tendon out of the way to touch bone. “Open,” she said.

Ow, I tried to say, tried to close my mouth, hide away my split tongue, but my own pain had parted my lips, now it was too late.

My mother looked for a long time. She let go. She settled back into her chair like she had never stirred. “Rupa is alive,” she said, not looking at me.

My anger made it easy to punish her. We gathered, my father’s family and me. We agreed she should be moved to a nearby home so that medical care could be on hand around the clock. They offered to cover what my money couldn’t. There was no talk of moving her closer to me. I was grateful, sick with the feeling. My mother’s chain was given to me. She would not take it with her just for it to be stolen. My cousins insisted. I think they felt sorry for me, stranger and strange, the last of my line. I was sorry too. I took the long rope of gold, a warm weight that smelt of her neck.

◆

I sold her gold to buy airfare to England and back, to cover the cost of a car to that house, the grand manor all my nightmares stemmed from. It wasn’t difficult to gain entrance. The child of that house, now a woman, was quick to respond to my email. I didn’t try to hide who I was. I told her I wanted closure. She sent me the address. I arrived in the middle of the day, many hours from darkness. Her butler opened the door. She employed many people now, mostly immigrants, her manor turned into a kind of bed and breakfast. People went in and out of that house all day, with and without children, and emerged unscathed. I felt a rind of doubt thicken.

She was a pretty adult, that pink girl I had so hated, her big eyes apologetic and faintly suspicious, her cheeks still rosy. I was likely unrecognizable to her, especially with my short hair. She handed me a document that promised I would not sue her. England had strict defamation laws. I signed. She led me upstairs. I barely spoke, hiding my tongue.

We stopped first on the third floor to look in at a little bedroom which still held only one twin bed. I could imagine Rupa and me so clearly, our small bodies in those stiff floral sheets, my sister keeping me up at night. She would wait until the whole house was quiet and steal all the blanket, leaving me to shiver awake. When she had my attention she would tell me our mother’s favorite story, the details subtly rearranged to emphasize the demon in the story, Raktabija. This demon had a power that almost overwhelmed the gods. Where his blood spilled, even a drop of it, another demon sprung up. He was impossible to defeat. The gods summoned Kali, who came and laid out her tongue and drank up Raktabija’s doubles and his blood, her endless thirst the perfect match for that particular evil.

My sister would show me her finger in the dark, marked with a little dot where she had pricked herself. Somewhere in the house her twin waited with fangs and a red mouth to eat me up, she told me, because we were too far from India for Kali to save us and besides, we’d been baptized, and that meant only the Christian god heard our prayers. He didn’t care about girls like us. Satisfied with terrifying me, she would fall asleep quickly, while I laid awake wishing I could be like Kali, dark and powerful, killer of demons.

The woman who owned this house cleared her throat. She was flushed from the stairs. I remembered her young face, much smaller, absolutely red with anger. Demon, demon, demon. I came away from our old bedroom. Up, up, we went, my breath coming faster. The house was far brighter than I remembered. It no longer smelled of greasy smoke, though the air was not clean, rife with the smell of cleaning agents. The windows had been replaced, the glass showroom clear. The walls were a blushing pink. The carpet was a vivid red that showed the tread of our shoes, like something from a film premiere. It made me nauseated.

At the top of the manor the last doorway opened into a meager hall, windowless. A few feet away it came to an end. No mouth, no tongue, no blood. My heart jerked, a split muscle. I entered the narrow passage. I felt disoriented. It was too long to be a closet. But the wall was just a wall. I put my hand out to touch it. Only the chalky feel of paint, then under that, warmth. I pressed and the surface gave, just a little, and when I took my palm away, there was a smooth depression. I stared. The pink wall with the print of my palm somehow looked exactly like the demon girl’s smooth upper lip, made very large.

I vomited, tasting bright salt, more sensation than flavor.

◆

My coworkers were all curious about my trip. I told them I got food poisoning on the flight there and hardly left my hotel room. It felt true.

“You poor baby,” Shreya murmured, “but why did you go?”

We were on cleaning duty in the students’ dorms. I resented the work, especially in the current heatwave, but everyone at the ashram had cleaning shifts to keep our egos in check. I tried not to grumble. My sexuality was an uncomfortable thing here, tolerated but not accepted. I was lucky to have this job. But the students left their quarters in terrible conditions. I was scrubbing one of the bedframes free of a new stain, something sweet, turned to mildew already. I had told Shreya the outline of Rupa’s death years ago, hoping to put her off from trying to befriend me. It hadn’t worked. “I went,” I said, “to see the house our mother took us to.” I doused the frame in more vinegar. I thought about Amma in a facility where she knew no one, offered three meals a day and a nurse and a bed. I wondered how often her bed was cleaned. It would never be enough. It was all I could give.

Shreya pulled more sheets from the thin beds, yellow mattresses exposed. “So many women take on caretaking roles, Kopal,” Shreya said, “if the money feeds your child—”

“Children,” I corrected.

Shreya looked stricken. I didn’t wait for an apology. I took a broom outside, sweeping the stairs to the dorms, biting the halves of my tongue, taking comfort in it. I had it cut along the lingual septum, that faint line even whole tongues show down the middle. Sometimes it still squirmed with hurt. Today the whole left side was tingling. Maybe the discomfort was only fair, punishment for mutilating myself. I didn’t regret it. Cutting my tongue in half had felt like winning something back from an enemy that had destroyed me. It fixed nothing, but it made me feel stronger, spiteful, and spite kept me alive. I could survive anything. I already had.

Shreya came to the doorway. “I’m sorry,” she offered. “Do you want to tell me more?”

When I looked up, I found her studying me. It prickled across my skin. I hated to see her pity. “Tell me about your weekend,” I asked.

Shreya, familiar with my moods, did.

◆

That night, I had trouble sleeping. I woke with a start. I looked at the floor before I swung my legs over the edge of the bed. Swollen hardwood, covered in dust and a few of my short hairs. I wasn’t dreaming. I went to the bathroom and washed my face and studied myself in the mirror. I looked agitated and old. I stuck out my tongue. One side lagged. My control was uneven sometimes, the two halves siblings, not twins. I smiled and caught my own flesh between my teeth, making my face like Kali.

“Kopal,” my mouth said.

What would Rupa look like at my age? Would she look so afraid?

“Rupa?” I whispered, feeling only one side of my tongue move.

◆

Rupa, who is at fault for your death, for the way it left Amma and me cleaved in two? Was it the house? Was it all of England, that small and powerful country, which did not want us? I was younger than you. Sometimes I wonder if the tongue came because I called it, because I wished for something to stop you before you destroyed me. I wanted it to shame you, not kill you. Maybe I was the one who should have touched it. Maybe it would have turned divine under my foot, and I’d bite my tongue in shame, and you’d be alive. Our childhood antagonism might have softened into friendship, the tongue a small nightmare only half-remembered.

But maybe if you were here you would hate me still. You never could stand it when I had something you didn’t. I remember your hot eyes on me as Amma braided my hair, gentler because I suffered in silence while you screamed and cried when she pulled your hair. I wished for tenderness from you maybe more than I wished for it from our mother. I know it wasn’t fair. You were hardly older than me. You were right to be angry. I should have been angry too.

I wish we could wake up small again in those cotton sheets, our bodies whole and too hot where they touch, your dark hair like mine on the pillow, a hard elbow or heel keeping me from clinging. You’re alive again. If your evil twin roams the halls, that means I’ve brought back only the part of you that loves me, so when I ask you to hold me you let me come close and put my head on your shoulder. We sleep without nightmares. I only have to ask.