There comes a time in a girl’s life when she will dance with her father. We know this because all the girls before us promise us so. They tell us about the suits and ruffled dresses; the curls and drugstore makeup. The glitter packed into eyelid-creases and sewn into gowns; the heirloom jewelry winking off wrists.

If this is true—that is, if justice exists, if promises are carried through—then there must be something that excludes us. We must not be girls.

Yes, I think that’s right. Look at us: three creatures huddled around a table, itching at our gym shorts, scavenging off each other’s heat. Meanwhile, the real girls sway in front us, their fathers wrapped around them like cages.

It’s alright. Don’t feel sorry for me. I’m not sad. Really, I’m bored. The chubby one with the kitten heels, though, is crying. Zhiwen, her name-tag says. I can feel her defenseless face fumbling for me. I ignore it.

It makes me so uncomfortable that she won’t just hide it, slip into one of the corners of herself like I do. I fold my napkin into smaller and smaller halves until it won’t fold anymore. I unfurl it, trace my hand against the grid when I realize the third girl, name-tag Katie, is watching me. I smooth the napkin on my thigh, tear it into pieces. But still, she doesn’t look away. There’s something about her, something steely in the eyes, that reminds me of how my sister used to look at me.

So, I do what I’m supposed to do. I take the crying girl’s hand and drag her beneath the skirt of the table. Katie follows.

I take off my left shoe, and then my sock, the only shred of cotton I have on me. Dab it at Zhiwen’s eyes; try not to be too rough. Only here, now that we’re closer, can I see the other girl is also crying. I fix her too. Might as well.

“Want to know how to stop?” I ask Zhiwen. She nods, not yet trusting her voice. I can feel Katie listening too.

I show both of them: how to pinch the space between your eyes, push your tongue against the roof of your mouth. For me it doesn’t work half the time, but they don’t need to know that.

Then, I draw myself closer, link my elbows into theirs, poke my fingers into their ears until they smile, our shadows swaying under the table to Sean Kingston and Flo Rida as we watch the feet under the table, each small shoe with its large counterpart.

“I wish my dad was here,” Zhiwen says.

“We all do,” Katie says. “But you have us.” It’s the first time I hear her speak, and I’m surprised by how low her voice is.

It’s my turn. I don’t want to say I miss my father, because I don’t. So I change the topic.

“Do you want to make a promise?” They turn toward me. They’re in the mood for promises.

“When we feel this way, we’ll find each other. And we won’t cry over them anymore.” I gesture toward the skirt; everything beyond it. The girls, the fathers. The ones who have left us behind. No—the ones we’re leaving behind.

“Okay,” Zhiwen says.

“Okay,” Katie says.

Suddenly, I want to reach out and touch their faces. Not for any reason, really. Just to see how they feel; if they’re sticky or smooth.

Underneath the table, we talk as loud as we can; steal an hour from three glow-in-the-dark wands and a few strips of confetti. We figure out what we are: eleven-year-old girls who believe in our fathers the way that we believe in God—that he exists, and that he rarely concerns himself with the operation of our lives.

The feet disappear. Voices high and low fade into the whirr of air conditioning; panes of tempered glass muffle car doors slamming shut. I lead them to the bathroom and we wash our faces before going home. As we part, I can see Katie smiling. Approving. She’s decided we’ll become friends, I think. Now that I see it, I let myself want it too.

◆

Shortly after we meet, Zhiwen takes an American name. She says it’s because she’s tired of people messing it up, though I think it’s because she wants to be more like us, down to the last syllable. And it works. When she becomes Wendy, Katie and I seek her out, our hands grasping for hers. And she takes them.

We sit near one another in class. Not next to each other, but in vertical rows, so that we can braid each other’s hair while the teacher tells us things we already know. We pass notes in our glasses cases, scraps of paper rolled into cylinders next to sticks of watermelon gum. We become very good at cheating. Katie does all the math homework, I give them my English answer sheets, and Wendy brings us extra packets of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. Our collaboration propels us to the top of the class.

We are efficient, clean, straight in that unthinking, prehensile way. We gather our hair into ponytails tied at the crowns of our heads; keep pen trimmers for our scraggly armpits in our pencil cases. We cut each other’s hair straight across with kitchen scissors; we reject bangs and layers. We wear glasses our fathers bring from home because they’re cheaper and better, metal frames lighter than a Sacagawea coin.

We are Christian. Not like the white “Christians” at school who only attend church during Christmas and Easter. No, we go every week in our slacks and collared shirts—Katie to Onnuri, Wendy to First Chinese Baptist, and I to RiverSong, a nondenominational Protestant church.

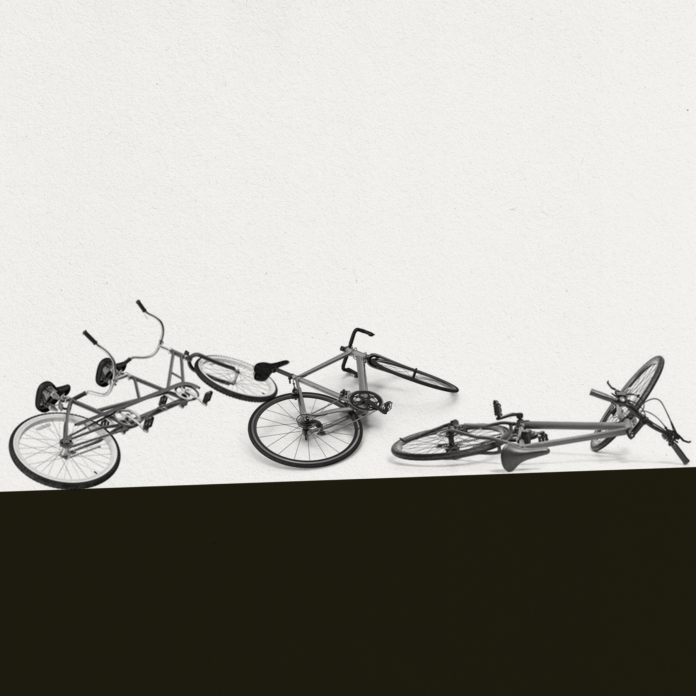

We bike to Target and split a pack of hair ties; scavenge the change jar to pay for field trips to the aquarium. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, we bike to school together, our instruments strapped to our bikes with bungee cords. We splay them horizontally such that they occupy the entire sidewalk, knocking off any pedestrian who does not part for us like the sea for Moses.

Listen—we are not fatherless. Do not call us that, unless you want your foot to be stomped, or your hard-earned name desecrated in a flurry of gossip. Our fathers visit several times a year. They bring us dehydrated noodles, pirated action DVDs, vials of pulverized herbs to rub into our canker sores. Other than that, though, they leave us blessedly alone.

We do not answer to our moms. We know their signatures better than they do. They are the ones who need our facility with language, and to them we are infinitely generous.

Which is to say: we are far more successful than girls with fathers at home. To have a father, we think, must be a deficiency. No, we do not bother thinking about them, except when circumstances insist upon reminding us.

This is the year we turn twelve, which means that it belongs to us more than all the other ones. We switch from camisoles to training bras, roller backpacks to Jansport, Asian boys to white, though they don’t choose us back. Not yet.

It is the year of the rat, the first time our lunar animal comes back to greet us since we were born in various university hospitals scattered throughout the United States. Back then, our fathers were poor graduate students in their Goodwill boots and church-issued winter coats, still living with our moms. What a surprise it is to us that they are there, reaching for us as we prepare ourselves to meet the world for the first time.

Now, we’re the ones who wait for them to come. They trickle in from their long-haul flights, bodies wrung of sleep and crammed with tasteless food. And even though my father comes every four months, I never get used to seeing him in my home.

The first few days usually wouldn’t be too bad. After a week, though, he’d get mean. Threaten to bring Michelle and me back with him if we misbehaved; take a wooden spoon and go at our hands. Other times, he wouldn’t talk to us for days. Even though we didn’t want to hear his voice, that was worse.

Michelle taught me how to take it. When I got in trouble, she brought me to her room, and that almost made me want everything that came beforehand. She showed me how not to cry. Stuck her finger in my mouth and flattened it against the roof. Then, she pushed the flashlight against her cheek until it glowed red, the light flickering her face in and out of darkness. It always made me laugh. And when I laughed, she did too.

In the early days, before our father could afford the trips to America, we waited together for mom to come home. Michelle microwaved my dinner, q-tipped my ears, and propped open the window so I wouldn’t overheat, though mom said at that point you were basically asking for the apartment to be broken into, and yourself kidnapped.

Now, Michelle spends all her time limewiring anime soundtracks, trimming her bangs, and denying that she’s gay whenever I sing, “Michelle! Is! Gay!!! Michelle! Is! Gay!!!” though I don’t even know what that means, only that it’s the word you use against high school girls who have never had boyfriends and are annoying. It makes her mad, but the kind of mad where she’ll chase me across our house, drag me by my armpits into her room, and tickle my stomach without mercy.

◆

I know my father will be home any day now, because mom is starting to clean the house and cook. When he’s away, it’s always Smart Ones and French bread pizza, but when he comes, she changes; something girlish rises to the surface, like the skin that forms on water left out too long. He says the food he can get at his home is better, but she keeps making it. He’s right. Her food tastes awful.

Now, mom crouches down and scrubs at the dust beneath the cabinets, runs the vacuum so it noisies up the entire house, and I go into my room and plug my ears with my fingers so I don’t have to hear. I sit with my back to the door and open my laptop, where I enter in my usual username, “officialdestinyhope31.”

“hiiii” I say. My words pop up in the penguin’s speech bubble. “wasup homiess… this is da real MILEY CYRUS :-)”

“ur lying,” says a purple penguin in overalls and a scarf.

“i can prove it!!” I type.

“hi miley,” says a penguin in a banana costume.

“i would be nothing without my fans,” I say.

“ur fkin fake!!!” another penguin says.

I shut the computer and crawl onto my twin bed, waiting for the stars on the ceiling to glow. They were painted there for another girl like me, before her family outgrew the house. I think sometimes about her and her dad—that he carried a ladder to her room and reached toward the ceiling balanced only on a rib of plastic, painted it with a brush thinner than a pencil. I’m scared for her also, of what his attention demands of her in return.

I am glad my father does not put stars on my ceiling. It means I owe him less. I don’t want to owe anyone anything. Mom always tells the same story when she says I’m being selfish.

Annie has five candies. If Michelle asks for one, how many candies does she have left?

Five.

I can’t remember when this happened; if it did. It doesn’t matter. Mom tells me to be more generous, and I try, even though she’s the one who’s always taking things from me. I’m the one who keeps my promises, gives more than I’m asked, fills in the sermon notes for her when she’s not paying attention.

I got my period at church a few weeks ago. My tummy hurt and I went to the bathroom, and I wasn’t surprised by it; my teacher had given me Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret to read in first grade because I was an advanced reader. So when my period finally came, it felt like something I’d been waiting for my whole life.

My underwear had bled all the way through, down to the crack in my pants. But I’d figured it out. I washed the pants with hand soap; lined my underwear with sheets of toilet paper I wrapped around the palm of my hand. I tied my cardigan around my waist and returned to my seat. I didn’t need Michelle, didn’t need mom, and they don’t know. Not even now.

◆

At school the next day, when our teacher makes us get into groups to discuss our diorama on My Ántonia, Wendy is impatient to tell us her news. Her father sent her a gift his latest package home, a red bracelet. She says he gave it to her to protect her from harm. It had once belonged to her grandmother, who was also born in the year of the rat. The year she turns twelve, it becomes hers.

And even though the bracelet is old, the braided strings no longer supple, we think it is working. Wendy seems luckier, happier, fatter even, the kind of fat that we understand to be a kind of wealth. She never brags about it, but I can see it dangling from her hand in class day after day, the frayed string that’s been wet and dried and wet and dried a dozen times. She wears it in the shower; isn’t thinking about how to make her possessions last.

So when we hear she loses it, we look for her everywhere, because she is our best friend. But a tiny part of me also understands it to be a kind of justice.

Some of the girls we ask say they saw her after gym, dry-heaving into one of the trash bins. Others say she went straight to the principal to ask for help. But I’m sure when he saw her, plump, ponytailed, fat-cheeked, the back ends of her glasses chewed as if by a small and greedy animal, he shrugged and suggested Zhiwen—oh, sorry, Wendy—check the lost-and-found.

And that’s where we find her, perched glumly beside the cardboard box of sweaters and dirty gym shoes. When she sees us, she starts pinching at her eyes, pawing desperately at her face. I realize that she’s using what I taught her. It makes me proud.

Katie hugs her, which means I have to too, and then Katie makes us promise to help her look for the bracelet after school. I think it’s a waste of time but I agree because I’m a good friend. And anyway, she needs us. She’s so useless by herself.

During sixth period, we knot Wendy’s hair into two braids so it stays out of her eyes when she bends over. We make them so neat and taut you can see her hair straining at the crown of her head. In the field after school, we sift through the grass on our hands and knees, the way my mom cleans before my father comes home, because she is afraid of his anger, or worse, wants to please him.

We scurry across the field, joints pressed into the grass, hands and wrists aching. The sky changes color several times, until it becomes that final color. But the grass yields nothing to us.

“Guys, it’s getting dark,” I say. “We need to go soon.”

We look at Wendy. Elbows and knees smeared with irrevocable stains. It’s so dark, I can barely see her face.

“We’ll look next week,” Katie finally says. “We’ll find it, Wendy. I promise.” I get up, and Katie follows. We wait for Wendy to get up too.

But then, Katie does something strange. She goes to her, even though Wendy’s so much bigger than either of us, with her gifts and hand packed lunches and honeyed snacks. Katie waits for her to stop hiccupping, for her body to slow its heaving. She lets her rest her head in her lap, though it looks all wrong. She tells Wendy she’s sorry. She runs her hands through Wendy’s hair.

(I would never let her do that to me. I would never let her touch my hair.)

“It’s okay,” Katie says to Wendy. “I love you.”

(She would never tell me that. I would be too smart. I would know she was lying.)

Katie pulls Wendy up off the grass, and astonishingly, she gets up. She leads Wendy toward home. The road is only big enough for two to walk side-by-side, and they leave me trailing behind. I have to stare at their arms wrapped around each other’s shoulders. I walk slow, to see if they remember I’m here.

I try Katie’s words under my breath. I love you. I love you. It sounds so ugly when I say it. I love you. Their chatter dimmed to night sounds. I love you. One block away. I love you. Two.

They’ve forgotten me. Of course they’ve forgotten me. It’s okay, I’m used to it. I can barely see them now; they’re nearly past the reach of the streetlights. So finally, I start running, before I lose them entirely.

◆

When we enter Katie’s apartment, her mom scuttles upstairs to her bedroom. The house is ours—the faded couch covered with sheets of rumpled plastic, the purple orchids, the rattan baskets filled with terrycloth rags. We spread the glue sticks and the felt squares and the shoebox that will become the Shimerda farmhouse all over the living room.

“Annie,” Wendy says, rubbing a piece of twine between her fingers. “Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure,” I say.

“Why did Mr. Shimerda kill himself?”

This one’s easy. “He was a weak man.”

“But what about his family?” Wendy asks. “Didn’t he care about them?”

I feel the bile gathering at the back of my throat. “That’s a stupid question. They would have been better off leaving him behind. He loved his country more than his family.”

“Annie,” Katie says, looking at me sharply. “Of course he loved his family.”

“He never says it,” I say. They want to show they’re better than me. But I’m the one who’s best at this. I did all the English homework for the year; annotated the books and gave them my answers. They were the ones who copied off of me, and here they were, thinking they knew the book better than I did.

Katie flips through her copy with one hand. “Here!” she says, her voice triumphant. “He asks Jim to teach Ántonia English. See? ‘Te-e-ach, te-e-ach my Ántonia!’” She wrings her voice like a rag, like she’s making a mockery of Ántonia’s father rather than proving something to me. She seems so proud.

“And how does that show he loves her?”

“Annie,” she says. “You know it. You know why.”

“Prove it.”

Her hands harden into fists. “You know I’m not as good with words as you are,” she finally says, sagging. “Whatever. Let’s just finish. The project’s due tomorrow.”

I wind a square of red felt around my wrist. We know I’ve won.

For dinner, Katie’s mom cooks us some kind of stew. It has a sour vegetable I spit into my hand under the table, throw away when no one’s looking. After we finish, we get ready to sleep, seal our bodies into the sleeping bags her mom quietly set up in the living room while we were eating. Wendy’s in the middle, and Katie and I are at her sides, and they’re whispering something that I can’t make out. I remind myself that their friendship cannot exist without me.

When I wake up again, it’s 1 AM on my Baby-G watch. The hour at which mom always comes home, the garage door whining open and forcing me up all over again, and it takes me hours to fall back asleep. Even here, in Katie’s quiet house, I still can’t stop waking up.

Wendy is sleeping next to me, gurgling a little. I sit up a bit further. Katie’s sleeping bag is empty. I look around the living room, but she’s gone.

I crawl out of my sleeping bag and tiptoe into the kitchen. I test the pantry doors, the doorknob to Katie’s room, but she’s not there, either. Not in the bathroom, the garage, or the forlorn steps outside her apartment.

I go upstairs, though I’ve never been invited there before. There’s a blade of light under the door, and I feel betrayed, but mostly relieved that she’s alive. Through the keyhole I can see her in the room, drawing me in like a beacon lit through a cheek from far away. Crying softly over something, I don’t know what, but her mom is humming to her, weaving her hands through her hair, but different from how I do it in class, when I tighten the knots as hard as I can, so she’ll be brave, and strong. I’m the loitering one now, hoping to brush even my shadow against the inside of the room, living off bits of stolen light.

◆

My father arrives on a Sunday. Mom makes me come with her to LAX to pick him up; she needs me to use the carpool lane. She lets Michelle stay home because Michelle always claims she needs to study for college, even though she’s already gotten into Berkeley. Whenever mom leaves, I can hear Michelle’s low voice through the door, chatting with random men on Omegle.

I don’t bother arguing, because when it comes to my father I never win. I sit in the passenger seat, socks against the dashboard, and flip through my copy of My Ántonia. We merge onto I-405, sit through an hour of traffic, enter the tunnel that leads to Tom Bradley, edging closer and closer to the rightmost lane until, finally, there he is, standing next to the curb, rigid with impatience.

My father. His BlackBerry is mashed against his ear. He’s surrounded by two large suitcases and a pile of battered cardboard boxes balanced onto a SmartCarte, wiping his nose against the collar of his shirt.

I climb from the passenger into the backseat, and mom opens the trunk for him to hoist his luggage inside. He steps into the passenger, pushes the chair so far back it crushes my knees. My father—this short, strange man in a jacket and white polo and beige slacks and my fat pastry nose, the one I always squeeze the sides of before I go to sleep. He smells just like me.

It’s silent on the ride home. Even though it’s still light outside, he goes into his room and locks the door to sleep off the jetlag. We’ve done this so many times I don’t have to be told to be quiet anymore. My mom is left outside on the couch, holding a dirty rag, and yet she’s smiling.

I knock on the door to wake my father when dinner is ready. He stumbles out like a frightened animal, eyes red and nose dripping. Mom spoons his rice and stewed pork into a bowl while Michelle and I serve ourselves. Meanwhile, my father unpacks his boxes from Malaysia—dried squid, powdered detergent, frozen fishcakes sweating into the cardboard.

We eat in silence. I leave to go to my room while Michelle clears the table, and then I hear him talking, then shouting in our language.

“Why’d you use my computer? Did you mess around with my files?”

“No, I promise I didn’t—”

“I can SEE that it’s moved since I last came here. The side was against the table; now it’s not. Do you think I’m stupid? Did you think I wouldn’t notice?” Michelle is silent. She’s doing the right thing, the thing she taught me. She’s waiting it through.

But he just gets angrier. He threatens to tear up her prom dress, withdraw her from tennis lessons, cancel tuition payments for Berkeley. I press myself against the entrance to the hallway, willing Michelle to just be quiet, just shut up and take his money. But she opens her mouth, and my stomach drops.

“Do it. I can’t control you. I’ll figure out my school myself.” Her nose runs into her mouth. I know exactly how it tastes—the salt and mucus, the gentle sting against parched lips. Her hands flutter toward her face. “Screw. You.” She turns and sees me at the vestibule; shakes her head. She storms into her room. Turns the handle before she closes the door so that the latch doesn’t make a sound.

He doesn’t follow her; he’s finished making his threats. Perhaps today he will finally go through with them. But for now he’s silent. His eyes are rimmed with crusts, the skin at his lips peeling in strips. When he returns to his room to sleep, I try Michelle’s doorknob, but it’s locked, some Japanese emo song pouring through the crack at the bottom of her door. I wiggle my fingers under it, willing her to at least touch my hand, which she used to do when we were younger, when we lived in the apartment.

We shared a room, and our father never came home back then because he couldn’t afford it, not even every few months. I slept in her bed and she slept in mine, and she rubbed my back, humming into the space next to my ear, shifting on cold days when I crawled under the covers so I could sleep in the damp imprint of her heat.

I can imagine her on the other side of the door now. Hands pressed into the crease between her eyes. Elbows locked on the table, the phone warm in her lap. I can feel it coming, more acutely than ever. The day she will leave me to bear this place alone.

One of the rules of the house is that I cannot leave without an adult, but the best thing about being a good girl is that no one ever expects you not to obey. I climb out my window onto the grass below, find my bike and turn it toward Katie’s house.

It’s not far away. Only fifteen minutes or so, even in the dark. Through her apartment window, I can see her eating with her mom even through the smudged plastic panes, and they’re talking, and she’s learning how to be loved.

A broken planter sits outside, a few dead flowers spilling onto my shoes. I sit on the steps until I can hear Katie and her mom putting the plates away. I flatten my knuckles against the door, but I can’t bear to knock. Turn around, walk back down the steps. The door opens before I can reach the bottom. I must have been too loud. So stupid. So stupid.

“Hello? Who is it?” Katie says.

I don’t say anything. I’d forced myself to stop crying, but you can still tell, if you’re paying attention, and Katie always pays attention. My left sleeve is soaked, my eyes near swollen shut, and I can’t stop gasping, even though I’m trying so hard not to make any noise.

“Annie? Is that you?” She steps closer. “What are you doing here?”

I walk away. Go to my bike. Push up the kickstand; hoist my leg over the seat. She runs toward me, and I raise my arm to shield myself.

But instead, she takes my wrist. Reels me in; reverses irreversible action. Does things I would have never let anyone who had embarrassed me in my own home and wronged me so badly do, except perhaps in a time before memory. She shuffles to the kitchen and comes back, handing me a cup of cereal. I don’t need to hear that she loves me, and she doesn’t say it.

Katie gives me her gym shorts and an old t-shirt to wear and walks me to her room. She crawls under the covers and waits for me to join her. I don’t think she wants anything from me. She’s just there, and I can’t understand why.

In bed, she wants to talk again about Mr. Shimerda, who played violin just like us, who wore a knit vest and a silk scarf on a farm and took off his shoes before he shot himself.

“Annie,” she whispers. “What do you think Ántonia’s doing now?”

“I hope she’s happy,” I say.

Because we feel sorry for this fatherless girl, pregnant and destined to bear ten more children on a cold, dust-bitten farm. The boy telling the story says she is happy, you can prove it, he says she keeps the fire of life even when she’s lost all her teeth, but he has left for the city, and since when have boys known anything about the condition of girls without men?

We are lucky, we think. Or at least, luckier. Our fathers are not dead. They are far too responsible to kill themselves. These men do not offer us protection, but the fact of their existence does, that they make our moms married and ourselves father-full, our lives smoothed out to the adults watching from far enough away. It soothes us that our fathers are out there, picking their teeth with toothpicks, roaming single occupancy rooms where they wake to deal business with men who have daughters just like us, in England, Australia, America, and other places yet unknown to us, or them.

We pull the blankets to our chins and talk, run our fingers along each other’s braces. I thread my elbow through Katie’s before I go to sleep. I will her not to touch my wet face. If she doesn’t know, then the promise isn’t broken. And she doesn’t.

I want so badly to tell her she’s right. Ántonia’s father did love her; it was all in the book. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. But I can’t. It’s stuck between the reeds in my throat, and I can’t get them to rattle no matter how hard I try.

Katie pets my hand and sings softly to herself, a Bible song from so long ago that I can’t place it anymore. It reminds me of my sister, and before that, my mom, and before that, nothing.

When I wake up again, it’s 1 AM, and I can’t remember where I am, and in that moment, thin as a nail clipping, I’m crazed with fear. But Katie is still there, and her small, wet hand is on top of mine, and her snores mean that she’s alive, and that, at last, helps me to remember.

◆

When I tiptoe through the door on the eastern edge of the morning, mom is stretched out on the couch, the knuckle at her throat pulsing in and out. I spread the throw blanket over her. Michelle joins me at the sink as I wash my hands and prepare our breakfast. She looks so tired.

Our father stumbles out of his room, his body gorged with sleep. He’s wearing an old Bintang shirt with holes speckled at the armpits, from a Bali trip he made without us. He looks so much like a child—a soft blanket wrapped around his waist, crumbs dangling from his eyes, baffled to find he still has a family.

“Michelle has something to say,” mom announces. Michelle plucks her headphones out, glares at her before turning to our father.

“Sorry,” she mumbles. Mom narrows her eyes.

“I’m sorry,” she tries again. “That I moved your keyboard. And that I yelled at you. I want you to pay for my college.”

I understand what happened now. Mom used the room key and barged into Michelle’s room and gave her the speech she always made to explain why he was gone, even though we really didn’t care, even though we knew not to say this, because it only made her more insistent.

He’d spent all those years working alone, squeezing his body into economy seats between Malaysia and here, bringing home money tucked in between the pages of the Bible when he visited so we wouldn’t have to pay a single penny for our tennis lessons and college tuition, no matter where we decided to attend. Ungrateful girls, you should understand his sacrifice. Now go outside and give your dad a kiss.

It works. It always works; that’s the part I keep forgetting. After the apology, our father doesn’t respond but something in his face loosens. Despite all his failings, he is never reluctant to forgive.

Michelle walks back toward her room. As she leaves, I can see her phone stirring in her back pocket, her hands already itching for its heat. I rise to follow. I can’t help it.

“Annie,” my mom calls from the kitchen. “Can you sit with your dad?”

So they know. My father’s at the dining table, a pile of Kleenex crumpled next to his cup. He always twists the tissue and pushes it deep into his nose; threads it out, pushes it back in again. It is spring, and it is my year, and he is allergic to the only place I have ever known, the place he brings me to turn me into something more dangerous than he is.

I walk back to the table, the tips of my fingers stinging with alarm and hope. I prepare to explain myself, to tell him I won’t ever leave without his permission again, just don’t bring me back with you, I HATE Asia, I hate how smelly it is and how loud and dirty the streets are, I want to be here with mom and Michelle, I want to stay in America.

But my father’s face is serene, and I realize he didn’t even notice I was gone. All he wants now is to memorize me, to steal my image away from me to take so, so far away. And I am generous. A girl who is loved. A good girl to the last. So I sit down at the table, and give it to him.