All that fall, we made a habit of entertaining hypotheticals about our eventual demise. Typically it was after a night out, with the liquor or whatever else we’d ingested still spiking our veins, lapping at the border of a new day. The hungover mixture of exhausted and wired unclenched the thoughts in our heads. Scraps of half-remembered jokes, the flotsam of drunkenness: Would someone shove us onto the subway tracks? Would we get diagnosed with an incurable disease? Would we forget ourselves and wander off a cliff?

You have to remember this was a moment in time when time itself collapsed; the seconds, the minutes, the days and weeks, sick with meaning, laid waste to the fourth dimension. It was the October following Trump’s inauguration, a year after the Cubs won the World Series, simply the most recent season of our discontent: political scandals and mass shootings, natural disasters and migrant crises. I hadn’t been laid since Independence Day. Our general disposition was bleak, but in a knowing ha-ha sort of way. A certain brand of softcore nihilism bastardized notions of “self-care”—we were buying shit and eating shit and drinking shit and snorting shit because who cares, hey, we deserve this, but also because who cares, the world’s going to end anyway. “We have a license to kill ourselves,” someone tweeted that month. Has there ever been a moment in the history of the world, I wondered, while watching The Bachelor on my laptop, when so many things matter so much for such a short amount of time?

Another routine night began at our default spot, a raucous dive on the corner of Meeker and Metropolitan. The four of us—Jason, Carly, Roy, and I—occupied a corner booth. The table told the same sad story. Rings of stale beer, still white with foam. A small puddle of tequila. The dregs of a frozen margarita gathering at the bottom of a glass. An open pack of Marlboro Reds, one cigarette ostentatiously peeking out. We’d reached the point of the evening—five or six in, the volume in the bar shifting from loud to pleasantly deafening—when everything felt like it was about to tip over.

“Here’s the thing about dating in New York,” I heard myself say, despising every word. “Dating in New York is like living in New York. It’s pure transience. We always, like, think there’s a higher-paying job we can get, a hotter guy or girl we can sleep with. We always think there’s a better place to be, even though we’re already in the better place to be. How tragic is that? We spend all this time in the greatest city in the world wondering whether we should actually be somewhere else. We’ve made it. We’ve arrived. But by virtue of being the kinds of people who have made it, have arrived, we can’t actually allow ourselves to stay. We keep thinking there’s somewhere else we can go. We keep thinking we can be happier. Which actually just makes us sadder.”

The words settled in my head. A flood of sorrow rose in my chest. I burped: acid reflux.

Then Jason delivered the punch line: “And that’s capitalism.”

Roy took a sip of his beer, his glasses slightly fogged. By the jukebox, a few girls dressed like school bullies from the mid-aughts danced lazily to “…Baby One More Time” by Britney Spears. Their eyes were glazed over, but they were smiling, swaying their bodies to their own private song.

“We all moved here because we felt too comfortable, because we wanted more,” I continued, loving myself now. Roy had given me some bad boy powder in the men’s room, and the high came on bitter and beautiful in the back of my throat. “So now when we get into a relationship, even if it’s going well, it’s going poorly. And if it’s going poorly it’s going poorly. There’s no winning.”

“What about us?” Carly asked, squeezing Jason’s arm. She had clearly heard a version of this speech one too many times, to the point where she wouldn’t even entertain it out of an innate Midwestern niceness.

“But see, you guys met before you moved to New York,” I countered. “It’s not the same.”

“Yes, Carly, what Nate is saying is we settled for each other long before we had time to realize we were settling.”

Jason smiled. He had a wiry build with a shock of black hair going gray and also falling out. Since moving to the city a few years ago he’d grown increasingly thin, emaciated even. So had Carly. In all black, they looked like tally marks. Neither of them were unhealthy—it wasn’t like they didn’t eat or worked all the time. They had a pretty typical diet, they drank a lot but no more than any other 29-year-old New Yorker, and when they did do coke they only took key bumps. But it was as if the city had put them on spin cycle, like its pace had sped up their metabolism, and though it was fair to say they were literally disappearing they were also never happier, disappearing.

“The problem is,” Roy said, “every conversation in this town falls into one of two categories: sex or networking.”

I’d heard this one before, but when Roy got drunk he was liable to repeat himself.

“It’s really that simple,” he continued. “No matter what, we’re using someone or getting used, playing someone or getting played. When we move to this city we all agree to this social contract, whether we realize it or not. It works for us. It puts us on the same page. Anyone who’s adept at reading social cues can tell which type of conversation they’re in. The trouble is when you can’t.”

He pointed his finger at us when he uttered the last phrase, for emphasis or something.

“What happens then?” Jason asked. He was playing dumb.

“You have to set the terms.”

“But isn’t sex and networking the same thing,” Carly chimed in, “when it comes down to it?”

Roy nodded: “Exactly.”

Suddenly I was on my phone, checking Instagram and swiping maniacally through Tinder, which had become a subconscious tic of mine once I passed a certain threshold of drunkenness. I didn’t have enough data, so none of the pictures could actually load; all I could see were an endless series of girls’ names and white squares stamped with those circling dash marks, anxiety-inducing ducks in a row, going ‘round and ‘round, leading nowhere. I was swiping pure potential, pure romantic projection. Even if I got a match (“rare”) I never acted on it (“dark”).

“Anything good?” Roy asked, peering over my shoulder. In the corner I watched the dancing bullies transmogrify into a gaggle of marketing execs cosplaying poverty in Dickie’s workwear and derelict jean jackets they’d undoubtedly purchased from a Beacon’s Closet. I couldn’t tell if they were having fun or if they were just trying to have fun, if there was even a difference.

“Same old, same old,” I said, swilling my beer. I couldn’t believe it was still almost entirely full.

“I’m telling you, man,” Roy began, realizing I knew what he was about to say. “Gotta go Premium.”

Unlike me, Roy actually got laid on Tinder. He told us one time in a rush of off-brand confession (“Adderall”) that the year he broke up with his girlfriend in Silicon Valley, he’d managed to sleep with over 50 women. He’d crunched the numbers. Run the statistics. Developed a kind of technocratic Pick-Up Artist algorhythm (“yuck”). There was a window of time during which Tinder-ing was optimal. It varied city-to-city, night-to-night, but in New York, on a Saturday, it was roughly 12:45 to 1:15am.

“Past 2am, they’re already home, and they’re not going out once they’re home,” Roy told me, again and again, unequivocally and without a doubt hating himself. “You gotta get them while they’re tipsy, but not drunk. While they’re out at the bars.”

And all you had to do, according to Roy—whose main photo didn’t even include him in it, only his black 2011 Porsche 911 Carerra 4s—was to text them: “Hey.” All you had to do was make a bit of small talk, so they knew you weren’t a virgin. All you had to do was, once the clock struck 1:30am, ask them, “Wanna come over.” Don’t even punctuate the question with a question mark. Simply suggest that the question isn’t even a question, but a matter of preordained fact.

“What about when they actually come over?” I’d ask him. “What happens then?”

Roy would look at me: “What do you mean?”

“Like, do you talk? Do you pour them a drink? Do you—” I paused, “—listen to music?”

At this point Roy would adjust his glasses and reliably deliver a sort of exaggerated sigh, and—I loved this part, hated it—say, “No, dude. You fuck.”

◆

En route to the next bar, I badgered Roy to buy more Stay Awakes.

“Already on it, boss,” he said. When he got drunk, he called me boss, in a way that both made him feel like my daddy and me feel like his daddy.

Six drinks had tripped into seven, as someone bought another round of shots, as someone bought cigs, that someone being me. We’d left our bar and started down Metropolitan, under the BQE, past the antique shop that was never open, looking into the pizza place, which sold four-dollar slices; walked past the barbeque joint with the suburban-looking patio and the fire station, its glass walls glinting in the moonlight like the Whole Foods down the block, and then on past Roebling, past the place called Extra Fancy, the name of which probably started out as a joke but then became true, the drinks were overpriced there and the inside looked like the set of Cheers. We were zigzagging along the sidewalk with our cigarettes in our mouths, smoke trailing behind us, the tequila-coke combo a picnic blanket someone unfurled and spread out over the grass, no creases, the nicotine like the wind brushing against your ears.

We got in line at the honky tonk bar on Berry. I checked my phone; I had a match: Lucinda. She’d even messaged me: “Hi.”

“I got a match,” I announced, to no one. Then I told the crew for the umpteenth time that this was the block where they filmed that TV Land show, the one about the fortysomething single mom who pretends to be 27 in order to qualify for an assistant job at a legacy book publisher.

“It’s pretty meta, actually,” I said, again, the words bilious against my tongue, “because TV Land, which replays old TV, is using the show to appeal to a younger audience.”

The Manhattan skyline loomed in the distance, dumb hunks of metal to point at and state the obvious.

“There’s my guy,” Roy said, looking across the street. “I’ll be right back.”

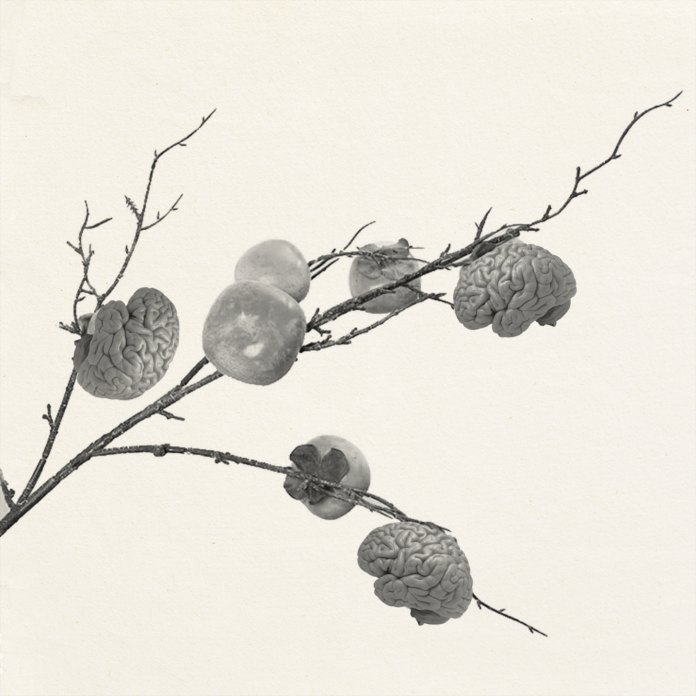

We watched Roy skip across the street and get into a white SUV. The windows were tinted. Or it was just nighttime. Either way, we couldn’t see inside. When we heard the gunshots, we just assumed it was a car backfiring, until Roy’s body rolled out onto the pavement. Bits of brain spilled out of his head, like a bowl of wet food a kitten had gently tipped over onto the floor.

“Fuck,” Jason said.

We all stared for a moment, while the bouncer continued to usher people into the bar. We were next in line. I turned to Jason: He wore the grave expression of a man who was being tickled against his will.

“Should we still go in?” I asked.

Inside, the band was playing a song I thought I recognized. Peanut shells lay strewn on the floor, crunching under our feet. Jason and Carly made their way towards the bar.

“Is this a cover?” I asked them, nodding towards the band.

“I don’t think so,” Carly said.

At the bar, Jason ordered three coffee drinks. They were like Frappuccinos spiked with vodka, inside the kind of coffee cups you only found at bodegas that mostly didn’t exist anymore. It was supposed to be cute, I think. I responded to Lucinda on the app: “Hi, what’s up?”

“This fucking bartender,” Jason said, predictably combative, “he acts like I don’t exist. I exist, guy. I fucking exist.”

When the drinks came, Jason didn’t thank the bartender, just left him a tip and turned around angrily. The night was in full swing now. I could feel it coursing through my veins.

“Is Kev coming?” he asked. “Because I feel like he hates me.”

“He’s coming, and he doesn’t hate you. He just doesn’t get your shtick yet.”

“What’s my shtick?”

I considered the question.

“Relentlessly aggrieved.”

A girl sat alone at the bar, swiping through profiles on Tinder. Swiping left on everyone, though some of them were blanks, like mine. I had the distinct feeling that her eyes would be a piercing blue and she would share her smile like a secret, and that when she turned to look at me, she might really see me, you know? (“Haha.”)

Lucinda responded: “About to go out with some friends in Williamsburg.”

“Do you want to try that, like, in real life?” I asked the girl, gesturing towards her phone, pocketing mine. Her eyes were halfway between blue and green, like they had been in the process of turning green but had quit halfway.

“I guess.”

“Wow, so that worked.”

“Sure did.”

“And here I thought I was being a creep.”

I could barely hear her.

“It’s sort of inherent to the process,” I think she said. “You have to be a creep to hit on someone at a bar. But you’re not a creep if you’re successful at hitting on someone at the bar. It’s a catch-22. I’m a catch-22.”

I loved how smart her literary references made me feel.

“Do you ever wonder what it must’ve been like for our parents?” I asked. “How much easier it would be to talk to people if you couldn’t talk to them online? Nowadays it’s weird because we have the choice, you know? To not do this.”

I couldn’t even hear the words coming out of my mouth.

“It’s great to meet a guy who gets it,” she probably said, although whether she was being sarcastic or not, I couldn’t tell.

“I get paralyzed, you know, just at the thought of hitting on someone. I don’t want to be a bother to anyone. I’m trying so hard to be a good guy. But I’m trying so hard I’m paralyzing myself.”

“You’re receding into the distance,” she said. “Your manhood is like the skyline shrouded in Hudson fog.”

The honky tonk music took on the character of the noise my fan makes when I’m sleeping.

“This is going to sound weird, but I feel like I can trust you,” I said, coughing into my bicep. I craned my neck over the bar to catch her eye. “Okay, I’m just going to come out and say it: I don’t want to have sex with you tonight. I know I’m supposed to want to, I know you think that’s all I want, but I really don’t want to. This probably sounds like a line, but I really don’t want to.”

Jason and Carly, with their matching black turtlenecks, grinded in the dark, gyrating, bodies melding.

“The truth is,” I droned on, “you don’t like me enough for me to believe you won’t mind me being bad at sex, which means I definitely will be bad at sex. You have no idea how worried I am about making this worth it for you.” I let this sink in, then followed it up with a joke: “I’m like an up-and-coming female director in Hollywood opening a tentpole studio movie—like, if the thing flops, will they ever give another woman a chance?”

I haha-ed at myself.

“The irony is, I’m actually good at sex. I just have to lower your expectations first. I have to know you’ll still have sex with me, even after I fuck up.”

She took a sip of her drink. All I could see was the sorcerous color of her pupils, radiating from the darkness. “Go on,” she might’ve said.

“What I’m really looking for tonight is for someone to hold me. Just hold me. Rock my head against your breasts, tell me everything is going to be okay. That’s it. That’s my kink.”

She couldn’t possibly be into this.

I kept going, despite myself: “I have this recurring dream—or maybe it’s a nightmare. I have this recurring dream where I come home for Thanksgiving, and I run into my high school girlfriend at the local bar. It’s been years since I’ve seen her—probably a decade. I honestly never even think about her. She rarely crosses my mind. But in this dream, I still love her. I’m filled with desire, in this dream. I can’t hold her whole body in my mind, but I can conjure up the details. In this dream, I want to lick the freckle that attaches itself to her lower lip. I want to bury myself in her unwashed hair. I can smell her smell, in this dream I can smell her smell, which I’d forgotten I even remembered. She smells like antiperspirant and puppy. And I don’t know how I know but I just know I love her and she loves me back. She flashes the same smile, where she looks like she’s only smiling with half her mouth, her eyes wide and mad with love for me, like I’m the most important person on the planet.”

I searched for the remains of my drink through a straw.

“We don’t have sex, in the dream. We don’t even kiss. And when I wake up, I wake up yearning. I’m devastated and confused and I’m, like, looking wildly around my room. It’s like I’m searching for something I hadn’t realized I lost.”

As she turned her head away her body became amorphous, indistinct among the others along the bar.

“It’s not like I miss her,” I said. “I just miss the feeling, you know? I miss the sensation of being somebody’s favorite person.”

The band—they were definitely doing a cover now—had reached a God-like volume, all-consuming if not overpowering.

“I’m nobody’s favorite person,” I said, repeating, “I’m nobody’s favorite person.”

◆

Am I actually sad or is my sadness just a bit? I thought to myself, as we stumbled to the next bar.

Kev had joined us, and he’d brought along the girl he was having sex with; Kev always had a girl he was having sex with. This one’s name was Annie. She had the pert body of a Pilates instructor and the big curly hair of a ‘90s sitcom star and the sex appeal of a very expensive chair.

“Are you my mommy?” I’d asked her.

“Ignore him,” Kev told her. “He’s joking.”

It was true: all of Kev’s girls were my mommys. Sometimes, I pictured them living together, a harem of interchangeably stupid-confident aspiring actresses in a spacious loft on Bedford dappled with sunlight and spindly house plants, wearing yoga pants and tight-fitting tops, gripping scripts for an audition for a guest spot on Law & Order, all of them passing around the same dog-eared copy of the white feminist essay collection du jour, carrying around New Yorker totes and a dream.

“I bet they suck good dick,” Roy would say matter-of-factly, when one of them stopped by our apartment to see Kev, his shirt losing the battle against the muscles underneath.

“I bet they’re not even afraid of dying,” I would respond.

The BQE rose up in the middle distance, ancient and sepulchral. I’m not sure whether I’m really sad or if my sadness is just a bit, I thought to myself, again. The coke had a tendency to parrot my own phrases back to me in ways both caustic and profound. The truth was my sadness wasn’t all that sad. I was white, male, hetero, privileged, in relatively good health. I wasn’t clinically depressed. I hadn’t been assaulted, or abused, or disenfranchised, or unemployed, or stopped at a border, or forced to go hungry. I had shelter. I had clean sheets. I had a decent job. I had healthcare. I had money. My parents had money. I had friends. They had money. Some people thought I was funny. Some even found me charming. I wasn’t handsome but I wasn’t ugly. I laughed often. I could dance, when pressed. I wasn’t immune to the galvanizing power of art. I enjoyed the finer things in life—French food, natural wine, recreational drugs, Marlboro Reds, a well-made daiquiri. I didn’t have sex that frequently, but how many people did? Most weekends I had plans. On Sunday mornings, the afternoons splayed out before me, naked, pliant, I felt the world open up to me sweetly, as if time had planted a gentle kiss on my cheek. I wasn’t sad because I couldn’t be sad, and yet I was sad, but I couldn’t be sad, so my sadness must be a bit, because I couldn’t be sad, but still there were times, late at night or first thing in the morning, when the pressure of my loneliness and the force of my desire to dispel it manifested in a physical tug. It felt like watching a nuclear blast on TV with the volume turned off; it was enough to affirm the existence of the soul. Oftentimes, I would call my mommy (my real mommy).

I felt my phone buzz. God? No. Lucinda: “Meet me at Ontario Bar?”

“Do you think climate change is really real?” Jason asked Kev, who was leaping off of cars and truck flatbeds, swinging his body around the poles of street signs, skipping gracefully from stoop to stoop like an American ninja warrior. “Do you think it’s all just, like, a cosmic joke?”

I turned back around to see Carly standing under a streetlamp, only to watch as the puddle of light swarmed her skin like a million shimmering bugs, violently but also gently—she didn’t seem to be in pain—until all that remained was an afterimage of her silhouette, the blue-black static you see when you shut your eyes.

Jason had stopped in the middle of the street. He was still talking, ranting, preaching, mad. He was doing a bit. Ladies and germs, he was doing a bit.

“It’s not that I don’t believe the science, I just don’t know what to do about it. Every time I stop to think about it I want to die. I mean, the scale of it. The refugees. The natural disasters. Inevitable wars over drinking water. And then there’s just, like, us, living here still. Partying. Going to the Metrograph. Eating $18 hamburgers. We’re just living and all we’re really doing is recycling. Which I heard the other day was pointless, because the city has nowhere to put it. And using paper straws instead of plastic, while we sip our bloody marys and wheatgrass smoothies, feeling good about ourselves, like we’ve fucking done it. But in truth, not feeling bad enough to actually do it, do anything. Because the truth is we don’t have to do anything. Not us. We really don’t. And I don’t want to do anything. I mean, do you?”

I looked around for Kev, but he and mommy had left as swiftly as they came. To have sex that often, I figured, is to experience a perpetual sense of urgency.

“It’s the end of the world and I actually feel fine,” Jason said, before fading away. “How messed up is that.”

◆

They’d set the lights down low in Ontario Bar. A framed photo of Rob Ford sat perched on a shelf with plastic bottles of whiskey. The only beer on tap was Molson Canadian. Two men of indiscriminate age with mustaches and beanies shot pool in total silence in back, the balls clacking together with a revitalizing thwack I could feel in my loins. A Celine Dion song hummed on the speaker system.

“Nate?”

A girl sat at the bar in an oversized winter jacket, much too big for how cold it was. She had a round face and small eyes and full lips. A mole tenderly situated itself beside her nose. Her t-shirt had a wolf howling at the moon on it, like something you’d pick up at a gas station in rural Wisconsin. Upon approach, I noticed her black hair was shot through with streaks of faded blue. The way she looked at me, a slight conspiratorial glint in her eye, it was hard to tell if she was interested, or simply amused by the situation she found herself in.

“Lucinda?”

I bent over to hug her and she kissed me on the cheek, a gesture I presumed she’d affected after studying abroad.

“I want to tell you something straight off,” she said, once I’d sat down and ordered a drink. “I know it’s super late, but I’m not going to fuck you tonight.”

“Okay,” I said, sipping my Molson.

Somehow, I must’ve missed the optimal Tinder-ing window. Classic “me.” Roy would be rolling over in his literal grave.

“What do you want to do instead?” I asked.

“Let’s just talk.”

She proceeded to tell me, unprompted, about her last boyfriend. He was a 42-year-old drummer in a Talking Heads cover band. While they were dating, he’d still lived in his mother’s garage in Queens.

“He was unhealthy and out of shape, and honestly”—she paused here for effect—“his band’s covers weren’t even that good.”

They’d broken up, but he’d still exerted some sort of weird control over her, she explained. She chalked it up to the age difference.

“One afternoon,” she said, gleefully; I could tell she’d told this story before, “I stopped by to feed his cat. He was out of town for some show and he told me his cat was going to die if I didn’t feed it. Which I knew wasn’t true but whatever—I hated him but I didn’t want to risk having his cat die. So I went by to feed his cat, and who should be standing in the middle of his apartment but fucking Carolyn McCormick.”

“Who’s Carolyn McCormick?”

Lucinda paused.

“Dr. Elizabeth Olivet,” she said, as if it were obvious. “From Law & Order!”

“Oh, right,” I said. For emphasis, I added: “Dun-dun.”

She beamed.

“Turns out, Carolyn McCormick was his new girlfriend. I couldn’t believe it. But we get to talking. And I end up telling Carolyn all of it. My parents’ divorce. My dad’s remarriage. My mom’s boyfriend, who as a kid I thought just liked to play video games a lot, but was actually mostly addicted to meth. And the entire time I was talking—it must’ve been at least 20 minutes—she was just calmly watering the houseplants.”

Lucinda pulled out a vape and took a drag, blowing it out the side of her mouth like a jittery witness at a downtown police station.

“Anyway,” she persisted, “when I finally managed to stop talking, I looked around and this weird feeling came over me. You know when you’re a kid and you lose your mom at the grocery store or someplace, and then you think you’ve found her but it turns out she’s just some random lady with similar hair? That’s what it felt like.”

“What happened?”

“Well,” she said, “I realize the cat is nowhere to be seen. I don’t even see his food bowl anywhere. Not to mention, the houseplant Carolyn has been watering is poisonous to felines. So I ask her, I ask Carolyn, ‘Where’s the cat?’ And she narrows those icy McCormick blues and asks me right back, ‘What cat?’”

She laughed, then laughed at the fact she was laughing, then downed the rest of her drink. Was that the punch line? I couldn’t discern the point of the story, whether there was one at all or the point was simply for me to hear it.

“Crazy story,” I said.

She leaned over and kissed me on the mouth. Her lips tasted like whiskey but her tongue tasted like toothpaste. I felt the folds of her hips, the familiar surprise of another’s body against mine.

“Where’s your apartment?” she breathed.

“I thought you didn’t want to have sex tonight.”

“I was just saying that,” she said, her voice husky now. “Of course I want to have sex tonight.”

I was taken aback. Unbidden an urge came over me: I wanted so badly for her to sprawl out over my entire body, to blot me out of the world. To delete me.

“But you don’t even know who I am,” I argued instinctively, hating myself.

She burst out laughing, laughing so hard she literally tossed her head back and fell back on her chair.

“Wait a minute,” she said. “You thought this was about you?

◆

“If you jumped off that building,” Roy mumbled in his hungover baritone one morning, on the way back from the bodega, “would you die or just break your legs?”

He was pointing at the three-story apartment complex across the street from the Brooklyn Public Library, on the corner of Leonard and Devoe. I gave it a quick up-and-down, measuring the distance of the fall against the fragility of the human form. The thinking hurt my brain. My headache, I felt, had transcended my body and formed its own entity, an altogether separate pain to which my nervous system was only given contingent access. It hovered, cloud-like, wrapping the mid-morning light in gauze.

“I think you’d probably survive,” I said, marveling at how the simple act of walking could make the earth wobble under your feet. “What about that one?”

The building was five stories tall. There were balconies on the top, where from this distance the residents—a blond-haired girl in a knit sweater and her boyfriend, presumably, wearing a baseball cap slightly askew—had no cares or anxieties in the world. I imagined them talking about the wedding they’d attended the previous weekend, or airing petty work complaints, or making plans for dinner that night, it would be grand but intimate, candles and wine and something meaty but nutritious in the oven, probably fucking sweet potatoes. From below they looked happy. From below we all looked happy, I thought, hating myself.

“Bro,” Roy replied, eying the building. “You’d def die.”

A red Gatorade seemed to be melting in my left hand, as if it were reacting to my internal rot. Entropy, felt like the word. A word. It echoed in my brain, connoting science, the mere notion of which solidified my otherwise abstract existential woe.

“I think you’d have a chance,” I said, “provided you didn’t hit an air conditioner on the way down or something.”

I took a fortifying sip of Gatorade, the pain sloshing around my skull. I saw myself jumping, landing on my feet, breaking both legs, thoroughly shattering my metatarsals, but then generally being okay, just muttering “Oww” or something before asking for a drink, maybe a paramedic. I’d get surgery. I’d get crutches. I’d get physical therapy. We’d go out. Hit the town. It would be fine—it would be.

Everything would be fine.