The following is an excerpt from the short story collection You Never Get It Back by Cara Blue Adams. You Never Get It Back is available now from the University of Iowa Press.

◆

I was staying in Virginia for seventeen days that spring at an artists’ residency. The dorm building in which we were housed was a seventies-style structure with small, monastic rooms and shared bathrooms. The other artists were mostly middle-aged women; one hung up a plea for quiet in the morning, another for quiet in the evening, and I walked around gingerly, trying not to make noise. At thirty-two, I was the second-youngest in residence, the youngest being a dark-blondehaired girl from Washington, DC, whose boyfriend lived in South Africa and who went on long runs by herself in the late afternoons. Our rooms shared a bathroom, and we struck up a friendship right away.

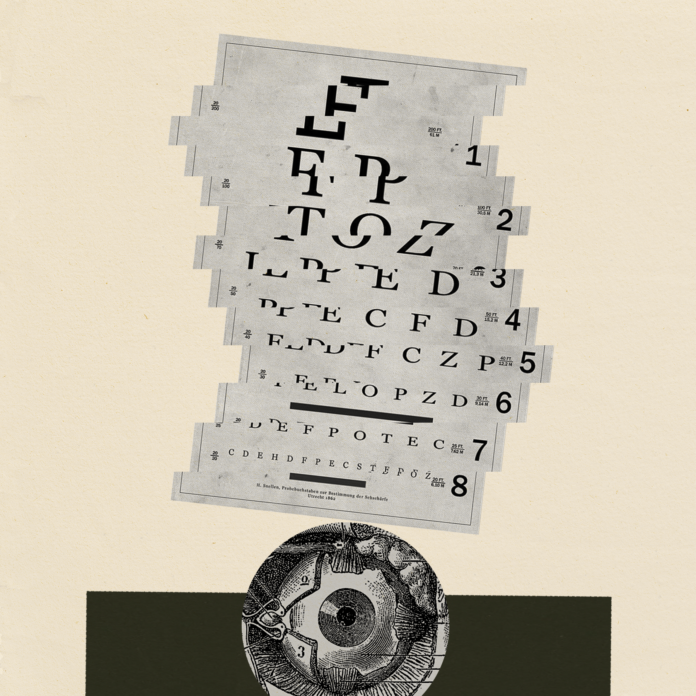

By the end of my third day, I had met almost everyone, except for one old man. On his face he affixed white surgical tape. The two half-inch strips began above the arcs of his bushy gray eyebrows and ran up the middle of his forehead, giving him a perpetually surprised look. This odd fact, and his lonerish quality, made him a figure of interest.

Mornings, he stomped glumly around the blushing green grounds, taciturn and anonymous. I would spot him from my window as I prepared to walk the quarter mile to my studio—our studios were separate from our living quarters—and each night he would pass me on the staircase in silence, failing to reply to my soft “Good evening,” a ghost with a limp and a cane.

Late in the evening of my third day, I asked a few others about him.

“Who, the old guy?” said Aaron, who occupied the studio across from mine. “He’s a painter, but I understand he has vision trouble.”

Sophie, the girl from Washington, DC, sat with us. We were drinking cheap wine in a windowless room shaped like a silo.

“Do you know anything about him?” Aaron asked her.

She shook her head, curls bouncing. “He never talks.”

◆

But when I entered breakfast after an early walk the next morning, the old painter approached my table.

“Is this seat taken?” he asked me, leaning on his cane, and I said, “Please.”

He carried a cup of coffee, which he set on the table, sloshing a bit into the saucer.

“What do you do?” he said. “I’m a writer,” I replied. “And what are you working on?” he asked, shakily lowering himself to his chair. When I deflected, not feeling up to discussing my latest efforts, the

dismal results of which made me worry that I had been wrong to quit my doctoral program, he began to tell me about his situation: he was going blind. He had lost seventy percent of his vision. He wasn’t sure how he was still painting, but he was. It sounded like a tough situation, I said, and asked him how he liked Virginia, trying to distract him from his obvious misery. This, however, was not a happier topic. He praised the countryside’s beauty and quietness and said he wanted to leave the city, but he couldn’t. He had been born there and he lived there and he could not escape.

“New York keeps sucking me in like a vortex.”

“You can’t leave?” I asked.

“No. I would be much happier in the countryside.”

“So why not move? Surely there’s a way.”

“My vision. Driving would be necessary in the country. But I’m still painting. I don’t know how but I am.”

“How do you know if they’re any good?”

He smiled, his expression wry. “Other people tell me.”

“. . . I’m joking mostly,” he added. “Natural light helps. In strong natural light, I can see a bit. That’s why I have the studio with all the windows. Twelve o’clock is best.”

As I finished my oatmeal, he extended a hand. His fingers were strong and blunt, the nail beds oddly flat. “David,” he said. “Nice talking,” I said, and rose to go to work, leaving him sitting there with his weak, milky cup of coffee, gazing out the window at whatever it was he could still see.

◆

But the words would not come. Each day, I sat alone in my studio in silence. One morning, I typed the first things that came into my head, and erased them. They were glib. Instead, I read. On small index cards, I copied out the words of others and hung these cards around my studio like small prayers.

One card read:

Her English-speaking voice is misleading: hesitant and lilting

with the nervous charm of someone who is new to a language.

A second card read:

It’s like being in a tunnel. Finally I emerge onto the brilliance of

the quai, beneath a roof of glass panels which seems to magnify

the light.

A third card read:

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones

A fourth card read:

That April I felt so heavy and I went to the sauna to feel less heavy

but it didn’t work. I went because I wanted to remember that the

heart was a muscle more than it was a metaphor: when it hurt

the hurt was most often a metaphor, but when the hot-cold-hot

of my rotation from sauna to ice bath and back made it thump

crazily against my ribs, that pounding was the muscle laboring

to keep me alive.

To do this I sat in the late March sunlight at my borrowed wooden desk, whose drawers smelled of mouse urine, as is the tendency of old furniture in warm climates, and used a thick, black-inked artist’s pen. The casing was a soft gray, of German manufacture. On its top it read 0.3. I was no artist; I had bought the pen because I liked its heft. The heavy nib exerted resistance when I guided it over the paper. I did this with care, like a person using an axe to tap a nail into a wall. It felt good to employ a tool I could not reasonably be expected to wield with any facility, to put this tool to work on an achievable task. The small white notecards I posted on the wall with silver thumbtacks.

My studio contained three windows, a twin-sized bed, and a flight of stairs that led down from a raised landing to the main floor. Outside, horses grazed. When I wasn’t copying out passages, I sat by a window with a view of the pasture, reading or just looking at the brighter world outside.

◆

The old painter was talking about painting. You had to know when to stop, that was the hard thing. Many young painters did not know and they ruined their work.

“Iberpotshke is Yiddish for overwork,” he was saying. “A beautiful, onomatopoeic word. And iber means over, so iber-iberpotshke is overoverworked.”

“So how do you know when to stop?” I asked.

“Practice. Years and years. And confidence: you must have confidence.”

His left eye bulged, pale-blue, sightless. His faded chambray shirt was unbuttoned halfway down his chest in the style of the seventies, white chest hair showing. Tiny, bright paint flecks of every color speckled the fabric.

It was 6 p.m. We moved into the dining room. I got in line and began chatting with a few women; he stopped to examine the chalkboard menu, though I doubted he could read it. Sitting down, I forgot about him. For dinner that night, the chef had made a bright sautéed kale and tough dried-out pork. The meat came apart in desiccated strips, white flesh clinging and fibrous. I had spent the day staring at the pages of a novel I’d written the previous year, a terrible novel. What made the words so bad? It was not each word on its own. Recombined, they might be okay. Some phrases I even liked. On the sentence level, though, the words became attenuated, uninspired. Not terrible, but mundane. It

was when the sentences piled on each other like logs making a hut that the thing became truly awful. This was, I imagined, like painting: you added color after color and you created an ugly brown.

I imagined torching the hut.

“I’m a good cook,” the old painter said at my elbow.

He had found me and sat beside me, though normally he ate alone in silence. Now, each time I spoke to the woman on my other side, he butted in like a recalcitrant goat.

“What do you like to cook?” I asked him politely.

“Italian, though I’m not.” He paused. “But I don’t like to follow a recipe,” he continued. “I don’t bake. I’m an abstract expressionist in the kitchen. I can go to a restaurant and eat a dish and know how to make it. I cooked better than all my girlfriends. They would go to my cooking school and go off and cook for another man.”

We shared a table with five women, all much older than me. By some fluke most people in residence were in their fifties or sixties, which had made me feel close to Sophie and Aaron immediately.

One woman, a German woman seated across from me, was truly old. She dyed her hair jet black and wore it bobbed, a little cap.

“So you never married?” I asked. “No,” he said.

“Do you have children?”

“No, fortunately or unfortunately. I consider it unfortunate.” He frowned, his browned, mottled face a pinch.

“The kale,” said a female printmaker from the Cape, returning to the table. She lived now in London with her husband, a banker, who funded her art-making. “I’ve found out the secret. Cook it with garlic and a little olive oil and cumin and add salt and lemon juice toward the end.” She was bossy, self-promotional. Her studio in London, she liked to complain, was poorly heated. She could walk there from her apartment but the route was not pretty; it was industrial.

“But that’s his recipe,” a middle-aged Dutch sculptor named Ilse exclaimed, meaning the old painter, who had correctly guessed the kale’s ingredients while the printmaker was away from the table. “But exactly!”

The old painter said nothing, smiled privately.

The printmaker was not impressed. The look on her face told us so. She didn’t like his complaints, having, perhaps, a life too full of complaint herself, and was not interested in what he had to say. He, however, could not see this. “Wow,” she said flatly. “Imagine that.” He muttered a modest “Well, yes, it’s always been a talent,” and excused himself, triumphant.

◆

He began to seek me out after this, talking to me whenever he got a chance. His face held a charge, like the electric air before a storm. The discontentment. I felt I was floating in space on a mobile, moving through air without a real home, and I recognized this charge: energy that wants to express itself in a transfer. Mostly, he talked about paint- ing. At first I tolerated him, but as time went on my interest grew. He spoke with such authority and passion about painting theory and his- tory and technique, the vocabulary of the brushstroke, I began to wish I could believe in a miracle. Maybe he could paint without the benefit of decent sight, what with the force of five decades of practice? Those decades must have value. But then he could make out only the brightest colors and sharpest forms. He told me so. I had a hard time believing even the most practiced hand could overcome this, except in dreams. What is a life? I wondered. A practice? Can it continue to move through space once it dies? The people who had died recently and who I thought of often in those days felt more fully alive to me than they had in life.

One of them, a close friend, had killed four people. The accident sent his car up in flames after the engine exploded, and I had watched it burn by the side of the highway in a photograph online before his body was identified, when the police were calling around to see if he was alive.

My first thought that day: I need to call him.

But of course at that point, at that temperature, there was no longer a cell phone to call.

I sat alone in my studio in Virginia now, and I thought of calling him. He would pick up and say, “Hello?”

And I would say, “Oh, thank god.”

“Why?” he would ask, surprised, and I would tell him what I was seeing.

We would discuss how his car had been stolen, the misunderstand- ing. His car, in which he drove me home on that same stretch of road one July afternoon.

It was hard to say his name.

In my novel, people moved around rooms. They picked up objects, spoke to each other. I couldn’t find it in myself to care. I changed their genders, but that did not help. It did, however, make the novel more unexpected. Perhaps the old painter’s work would be the same way: heedless, surprising. But that was, of course, no substitute for vision.

Aaron, whose studio was across from mine, was making a monumental abstract drawing. Or painting, rather: he sketched lines in pencil and went over them with brown ink. He made the ink by boiling black walnuts for hours in an old tin pot on the stove. He would invite me to sit and talk with him as he worked. I liked to lean against the wall, watching as he moved around the studio, washing brushes and sharp- ening pencils and putting on music and finding snacks for us. A week into my stay, I was sitting in his studio with him and a new resident, a microtonal composer with a special love for making scatological jokes, and I decided to ask them if they knew why the old painter used the surgical tape on his face. The men both shrugged. The question did not seem to interest them. Have you seen his paintings yet? I asked, and they shook their heads no. To his knowledge, Aaron said, no one had been invited to visit the old painter’s studio. This was not unusual. The idea was we should have total privacy if we so desired, privacy I often used to take a nap.

“Do you think they’re any good?” I asked Aaron. The microtonal composer and I sat watching Aaron trace lines on his enormous paint- ing, which was coming to resemble a vector.

“They can’t be,” Aaron said.

The microtonal composer made a farting noise. Aaron and I looked at him, startled.

“That’s my best guess,” he said. “You two aren’t very nice.”

“But you know we’re right,” the composer replied. Sophie walked by, humming to herself.

“Join us,” Aaron called to her. He had a crush on her; many of the men did. She was striking, with high cheekbones and cheeks perpet- ually flushed a sweet pink. She was friendly but disappeared a lot and was therefore mysterious. She’d shown me a picture of the boyfriend in South Africa, whom she’d met while volunteering at an orphanage. He was tall and handsome, with the straight white teeth of an under- wear model. His parents were wealthy, and he wanted her to come live with him on their family estate outside Johannesburg, but she had her doubts. Go live with him! I’d urged. What do you have to lose?

She wandered in.

Our conversation veered away from the old painter. Aaron looked at Sophie with such intense but expertly veiled longing that I began to hope she would break up with her South African and leave him to save orphans on his own. She liked Aaron, it was clear. But Aaron did not strike me as the kind of guy who would ultimately settle down with a girl like Sophie, nor she a person who would ultimately be happy with a guy as gently goofy as Aaron, so I continued to hope for her sake she would go to South Africa and have lots of great sex with the rich boy who loved her. If it seemed too good to be true, well, enjoy it while you could. Life was increasingly like this: full of impossible, contradictory wishes.

What can I tell you about my life at that time? It was a quiet life, constrained. I spoke little. I smiled. My friends did not know my true desires, my longings. I lived in a hot place far from home. The man I was engaged to marry was patient, the sort of person who never spoke over you in conversation. He waited to be sure you were done talking, and he waited a few extra seconds beyond. When I told him that my friend had died, he waited. He did not rush to console me. This might be why I had said yes when he asked me to marry him, a word I had never been able to say to another person. And when I said I was going here, to Virginia, he did not complain, said only, “Do good work.”

On the telephone, I lied to him. I said the novel was coming along. I said the fresh air and sunshine were inspiring. I said—but this was true, or mostly true—that I missed him. I entertained him with stories about

Aaron and Sophie and their thwarted love affair. I did not mention the old painter. I suppose I was waiting until I had more to report, though what that more might be, I did not yet know.

I kept hoping the old painter would invite me to visit his studio. He didn’t, though I dropped hints, and once, in violation of the rules, he stood outside my studio wondering loudly if anyone had seen me until I emerged. “Did you need something?” I asked him, irritated, although of course I had been doing nothing aside from staring at a blank sheet of paper—or rather a backlit replica of a blank sheet of paper—and he said he had merely wanted to know what time I was going to eat lunch. Tuesday at breakfast a few days later, the invitation came at last. The old painter asked me to visit his studio that afternoon, but only if I was interested, of course, he added anxiously, saying he would understand if I was otherwise occupied. I promised I was not. Well then, he said, come by between two p.m. and four p.m. He worked best when the light was strongest, so I was to drop in after that part of the day was over. I spent the next hours in my studio waiting impatiently for two o’clock to come, feeling, crazily, I knew, but nonetheless urgently, that in seeing his work I would learn something important.

“Come in,” he called at my tap, and, when I opened the door, “Thank you for coming.”

The place was airy, bright: large windows on three sides, a bed in the corner. On the radio, classical music, a light sound with strings and a piano. The back door, propped open, allowed in March sunlight and a hard, cold breeze.

He shut the door to the hallway, his cane clattering on the handle. Lingering by the door, as if reluctant to allow me in any farther, he told me he was thinking of departing the day after tomorrow, five days early. “If I leave with Henry I must begin to pack. He’s offered to drive me to New York. But I don’t know whether I should leave.”

“Do you feel you’ve finished your work here?” I asked him. “No, but I’ve been anxious. Unsettled.”

“About missing New York? Wanting to be home?” “No. Not that. Maybe about returning.”

“How would you go?” “The train.”

“I like the train, looking out the windows at the landscape.” “I don’t like it. I dread it a little.”

“Did you always dislike it?”

“No, since my vision has gone. It’s harder, all of it. A ride from door to door would be a relief. But if I go with him, I need to start packing today.”

Beyond where we stood, two white folding tables made a T. On these tables his paintings were arranged in long rows, two deep. We moved toward them. “They’re all vertical,” he said. “Arranged in the order I finished them. Which would you like to see first?”

The perhaps forty paintings were done on rectangular sheets of paper about fifteen inches by twelve inches. They were color field paintings made with acrylic and pastel so the paper’s grain was visible at the edges. The initial paintings were dark. They looked overworked. The middle paintings were best: unmuddied, quick and loose. One juxtaposed a deep blue with a bright orange. Another was green and white. The later paintings were simple, plain and undone.

“You choose,” I said.

He lifted a painting from the nearest table. A violet mass in the center, yellow at the sides. “Some of these I work and work. This one came quickly.” He selected a murky painting, red laid over black, four raised circles in the center arrayed like bushes rising up from the paper. “I work with a very wet brush. This makes me think of fire, and of trees. But I shouldn’t say that. I don’t like to influence the viewer.” Next, a dove gray painting from the back table, a royal blue streak on the left side, a loose black textural stripe forming a small curve reminiscent of a heart. “This one is for my friend who is a poet. She helped me with these immensely. It’s an elegant painting.”

He held a brownish yellow painting close to his face, perhaps a foot away. “How well can you see it?” I asked. We stood near the open door, sunlight on the paper. In the light the solid color field disintegrated, lighter streaks showing. “I did this one with the walnut ink that man made. What is his name?” “Aaron.” “Yes, him. It’s a beautiful, rich color.” It was not. Aaron had boiled and boiled the walnuts in a pot on the stove to leech the color, but he had grown frustrated. He’d gathered more walnuts from the grounds. Still the color was not deep. But he used it nonetheless: it was cheaper than buying ink. A failure, he’d said, but not a total failure. It was important to work quickly, he believed, so you could blow through your mistakes.

“Here I can begin to see detail,” he said, “the texture of the strokes and the paper.” He moved the painting around, a few inches from his face, scrutinizing small parts. “But it’s blurry.”

I described the lighter places, gesturing to where the field became a pale amber. “I’m glad to know that,” he said. “But in artificial light, in a museum or gallery, you might not see it. The lighting in galleries is always so bad.”

He chose the most recent painting on the table, last in its row, done in a wash of dark green. “What feeling does this give you?”

I thought about it. The word I thought was melancholy, but that seemed too gentle. “Dark,” I said. “A dark feeling.”

“Yes,” he said. “I was feeling very down. I ran out of energy.” “Despondent,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “Despondent.”

“If I leave with Henry, I should begin packing today. But I don’t know.”

“It would be a shame to leave when you’re feeling that way,” I said. “Maybe you should stay.”

“There’s no guarantee it would change,” he said. “But it is beautiful here, and New York is so ugly.”

“In March?” “All the time.”

He touched my arm. “When are you getting married?”

“October, I think.” “He’s very lucky.”

I thanked him for showing me his paintings, said goodbye, and slipped out. Closing the door, the cane rattled on the door handle. I heard a pause, and then him taking up the cane and moving slowly to- ward the stereo, turning it up, the sound of the classical music swelling.

So I had my answer. The paintings were, for the most part, childlike. The compositions had a minimalist appeal, but his execution was sometimes sloppy, the paper cheap—likely all he could afford, given the volume he produced—and any moments of grace accidental. What’s more, they were like Rothko’s work, but decades too late. He was like an athlete who could no longer compete but kept training. But at dinner that night, he said he was energized by our visit and no longer thinking of leaving early; he would perhaps even host an open studio. “Other people have asked about my work,” he told me, “and after your visit, I’m encouraged.”

I felt obscurely guilty; although I hadn’t lied to him, I also hadn’t told him the truth. At the same time, this was the happiest I’d seen him, and surely that was no small thing. He said that when I’d left his studio, he’d thought he was done for the day but had instead begun working again, new paintings coming easily.

Around us, others discussed New York. Talk turned to the storm. He joined the conversation. He had lost power for a week after Sandy. An explosion at the Con Edison power station had knocked out electricity in Lower Manhattan. He announced to the table: “After the storm it was remarkable. It was like there were two New Yorks: above Fortieth Street and below Fortieth Street. Damp and cold and no heat, and the people above Fortieth Street were living their lives as if nothing had happened.”

“On the contrary,” the Dutch sculptor named Ilse corrected him, for she, too, lived in New York, “I found that people were very kind and helpful. Not like in the seventies; no looting. In stores people handed you what you needed. ‘Do you need this? Do you need this?’ And they handed it to you.”

“Well, I don’t know about that.”

“Do you have neighbors?” she asked. “Neighbors are important, David.”

“How people could do nothing, I don’t understand.” “Do you have neighbors?”

“I do. I have one neighbor, and he amazed me. He walked all over the city to get food. He must have walked twenty miles.”

I asked about his life in the city. He had a closed-circuit television in his apartment, he said. He could put a book on the ledge and the television illuminated the page. The font could be made larger and darker and flipped from black on white to white on black. He listened to stories broadcast from Symphony Space, but it wasn’t the same as a book: you couldn’t go back and reread if your mind wandered. Each word was briefly there and gone. An old art teacher of his had taken him to hear Dylan Thomas read at the Kaufmann Auditorium in 1950, when he was in high school. Her husband was a poet, no longer well known, but included in the Weinberger anthology of American poetry. She loved Thomas. So did her husband. Thomas read “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” and “Do Not Go Gentle.” Norma Millay was a friend; she had recited her sister Edna St. Vincent’s poems from memory, quite a cut-up, and done voices like Tallulah Bankhead. He laughed a little at this memory. “You know Tallulah Bankhead?” he asked me. “The story about the little brown monkey she carried onto the stage during Conchita who snatched the wig from her head and ran off, and she turned a cartwheel and the whole audience applauded? She writes of it in her autobiography.”

“Another story goes,” he went on, “that a friend of hers brought a fresh young man to a party, a bit of a wit, and he told her he was taken by her—she was beautiful—and that he wanted to make love to her that evening, and she replied, ‘And so you shall, you wonderful, old-fashioned boy.’”

◆

After this he was happier, more sociable; at the same time, his depen- dence upon me grew. The next night at dinner, as I was busy talking to Aaron, the old German woman with the cap of black hair leaned in and began to speak to the painter urgently and quickly in her sparrow voice, sonorous and accented and hard to discern. She waited always for him, around corners, at the table, seeking him out, and once had stood by herself in a room, her hands clenched into fists, muttering about how he ignored her and liked to speak only to the younger women.

He stopped smiling and turned away. When I spoke to him, he said nothing, as though to punish me.

But later that evening, he joined a group to watch television. Five of us were watching Girls in the living room, near the staircase. From the top of the stairs, he overheard dialogue. He shouted, “I hear dirty talk! I’m coming down.” We sat on the couch, huddled together drinking red wine, so he pulled up a chair behind the couch and listened; he couldn’t see anyway. He kept mishearing, pestering us to repeat what the characters had said. Finally, I turned around and repeated, “He said, ‘I’m going to eat your pussy on the sidewalk.’”

“Aren’t you glad you asked, David?” Ilse scolded him, as he sat in shock, and we all laughed. He laughed too.

At the end of the episode, he asked me, puzzled, “This was written by a woman?”

“Yes,” I said.

“And this show is considered feminist?” “It is,” I said.

“Times change, I guess,” he said.

My chest began to unclench, and I thought briefly I was about to start writing again. But Saturday, bombs exploded in Boston. I had lived there after college, and the street was familiar to me, a place I often walked. The hours took on a strange, insulated quality. I read every- thing I could. Footage was eerily distant and close at the same time. Our wireless connection did not work in our studios, so I took out my cell phone in my dorm room and hit refresh, hunched over its face like it was a set of tarot cards. I had a sense the news might change. But of course all the phone’s screen could tell me was what was past.

On a walk before breakfast on Sunday, I came across a deer skeleton, flesh worn away by rain and air. The ribcage was beautiful. It was a poem. But even if the violence of death was a poem, it was still death. At breakfast Aaron invited me to go to church with him and So- phie. The church was a historic black Baptist church; the director had mentioned it, and they wanted to learn about the history. I said yes. I did not believe and did not want to intrude, and I regretted my answer as soon as I spoke, but I didn’t know how to say I’d changed my mind.

Once the three of us arrived, though, I was happy to be in a space I could sit with my thoughts amidst other people.

To open the proceedings, the reverend led us in giving thanks for all that we had. “I woke up today and I had the use of my limbs. I had eyes that could see. Thank you, Lord, for legs that can walk. Thank you, Lord, for eyes that can see.” Our voices followed his: “Thank you, Lord, for legs that can walk. Thank you, Lord, for eyes that can see.”

Once we were done singing the hymn, the reverend began his ser- mon. “The men in Boston, they wanted to do what God does, to take life, Lord have mercy on us. Don’t fail your test. Your children: you may have children, and they may be disobedient. Don’t fail your test. Monday, you may go to work and a person may not look you in the eye, may not say, How you doing? Don’t fail your test.”

As he preached, he shuffled his feet and gave a soft “huh” to punctu- ate his words. The effect was electric. It made me feel the words inside.

He wore a long white robe. By the altar, peonies.

Descending the stairs, he paused, gazing out: “And you may find that, like Adam and Eve, the weakness of the flesh is upon you. Our brothers and sisters in the Senate, they failed their test. Those men in Boston, they failed their test. Don’t fail your test.”

At the altar now, he called to us: “There may be some here today who want to be saved. You may come forward now.”

I wanted it, but I did not believe it was possible.

A woman in a gold-brimmed hat shifted in the pew ahead but did not rise. The right side of her face was speckled with many small, dark beauty marks. Paper fans had been distributed. They featured an adver- tisement for a funeral home, with a photograph of a serious man in a dark suit, red handkerchief in a breast pocket, and now she lifted her arm and fanned her face. The man’s face moved as she fanned, replacing hers and revealing it, replacing and revealing.

An old woman wearing a purple suit slowly rose and made her way to the altar.

“Don’t fail your test,” the preacher implored as she walked, looking out at us. His eyes were light, luminous yellow feldspar set in a field of white sclera.

Before dinner on Monday, I walked in defeat to the main residence. It had been a long, quiet day alone in my studio without a thing to say. At dinner, the London printmaker who so disliked the old painter announced that she was having an open studio the following afternoon. He was displeased and muttered to me about it; he claimed he had been thinking of having his open studio tomorrow. Of course, he had said nothing about it, so he had no right to be upset. He retired early. I wasn’t especially interested in the printmaker’s work, but unable to stand the solitude of my studio the next afternoon, I decided to drop by. I went alone and stood with the others around the printmaker in an attentive semicircle. She rolled an orange soy-based ink onto a clear plastic plate with a small roller, the sticky ink spreading slowly. The pa- per she had initially been using, she explained, had been the wrong type, Stonehenge paper, and so the ink would not dry, because it did not dry, really; instead, the ink was absorbed into the paper. Before a show she had tried drying her prints with a hairdryer and heating them over the radiator, but the ink never set. Now she used a new kind of paper. This paper she soaked in water and lay between sheets of plastic to keep wet.

On the walls the printmaker had hung small prints reminiscent of wallpaper. She liked to use a grid pattern and a dot pattern.

Two women leaned in, examining a twelve-inch lavender medallion print, wineglasses in hand. Other people talked in small clusters. The old painter entered, stood alone. He had been very peevish since she had announced the open studio, and I did not join him; I felt worn down. I was not sure if he could see I was there. I doubted it.

The printmaker put the orange-inked plate on her drafting table and lifted a piece of damp white paper from the stack. “I’ve heard heavier paper is best,” she said. “Back in London, I’m going to try it.”

“Have you tried watercolor paper?” he asked.

“No,” she said. She spoke matter-of-factly. “It’s textured. Well, some of it isn’t, I suppose, but this paper works.”

“Oh,” he said.

The printing press was electric-powered. She registered the damp paper with a cardboard edge, aligning it, lifted the edge, and fed the paper into the metal roller. The roller needed to grip the edge of the paper before she laid down the plate.

He picked up a bottle of Akua ink and held it close to his face. “Is the ink made in Japan?” he asked.

“America,” she said. “A North Carolina–based operation recently bought the company.”

She put down the inked plate and ran the press. She wiped traces of ink from the press’s Plexiglas surface and laid down a second plate. “Middle-aged eyes,” she said, setting her glasses on the press.

“Better not forget to pick your glasses up,” the old painter said. She did not respond.

He moved nearer, leaning on his cane.

She ran the press again, using the orange print as the base, and held up the result. Dribs and drabs of gold paint had made blotches over the orange. We gathered around. She showed us the print, rotating slowly inside the circle of people.

The old painter pressed forward, putting his face near the paper so he could see.

“Okay, David,” she said brusquely, moving it away from him to prevent him from accidentally brushing against it, “I’m going to put this on the table to dry, and you can look at it over there.”

People began to talk. The old painter followed her to the table and examined the print. He had to lean down to get his face close enough to the paper to see, but he did not lift the paper himself. Instead, he stooped. His hands were clasped behind his back. He appeared to want to demonstrate that he would not touch it. He stayed that way for two minutes or so, hunched over the print. Then, without speaking to any- one, he stood upright and made his slow way to the door.

Outside, April was in bloom. Through the shared bathroom I heard noises from Sophie’s room that could only mean one thing: Aaron was getting his wish, and her South African boyfriend had reason to fear for her loyalty. Of course, they said nothing to me. Still, I was happy for them. Mornings, I sat on a stone bench beneath one especially enormous horse chestnut tree as chilly sunlight filtered down. The pale pink blossoms emitted an acerbic scent, like diluted bleach. My characters talked amongst themselves. I strained to hear them, but they wanted privacy. They were being mysterious; they moved away from me. I wondered who they were. Were they people I remembered? Were they the dead, come back? Or were they only me, myself, an echo?

Those days spent collecting data, recording the results: I had thought that writing would be the same. But in the end, it wasn’t; it required more.

I had nothing to say. I could hear nothing. I decided to quit. It was the honorable thing to do.

The painter was upset by the open studio visit. He wouldn’t say so, but his feelings were deeply hurt and he held a grudge. His mood plunged. In response he decided to hold his own open studio in two days, to compete with the London woman. He would be more popular: I think that was his hope. He hung up signs on doors with the date and time written in a large, shaky hand and positioned right at eye level. Then

he began to worry that no one would come. At breakfast he pestered people, wanting them to insist on visiting. He would ask if they had seen his sign, saying he was concerned the sign was easy to miss if a person was not paying attention. Then he would say he hoped he would not be overrun with visitors, as he tired easily. But of course he hoped they knew he didn’t mean them, he would add; he would certainly want them to come, if they felt the event was of interest.

He carried a small white box with a clock and a mechanical voice. A tone would sound and the soft female voice would announce the time. As he encouraged people to come to his open studio, the voice would interject: Eight a.m. Eight fifteen a.m. Eight thirty a.m. Eight forty-five a.m. Nine a.m.

At night now, he preferred to retreat to his room and play classical music on his small stereo. He would tap his way up with his cane and leave the door ajar. He didn’t take care of himself as well as he might. He gave off the warm, human smell of flesh lived in. It was not entirely unpleasant. It was the smell of an older person who did not like to wash more than was necessary. The smell grew stronger, became that of a person turned a little feral.

In my studio, I read. I was done writing.

I was afraid, but I fed the horse outside my studio window an apple left from lunch, holding it out to him open palmed, as I had been taught as a girl. His teeth were big and yellowed, nostrils large, and when he moved away my hand was wet.

“I’m coming home to you,” I said on the telephone, and while the love of another person was not enough to make up for what I could not do, it was what I had now, and I was grateful the way a person was grateful now to have legs.

The day of the open studio came. I tried to enlist Sophie and Aaron to go with me; the old painter was so nervous and I wanted to make him happy. The three of us arriving at once might do it: he would feel admired, loved. We weren’t exactly a crowd, which is what he kept

worrying over and obviously wanting, but we were a respectable group. Sophie said she was busy. Aaron was curious and said yes.

“Let’s go early,” I said, “to encourage him.”

“We’d better,” Aaron agreed, “or he might cancel the whole thing.” The painter had been in a dark mood at breakfast, convinced no one would stop by. But people had; we’d already seen a few returning, including the old German woman who held a torch for him, and when Aaron and I arrived, he was happy. “Come in, come in!” he said, opening

the door. “I heard you giggling down the hall.”

It was noon; he was not going to paint today because he left the next day and was worried the new work would not dry. The back door was open, but the studio was not so cold this time. The morning chill had abated, the April wind less punishing than the cold March gusts. “You came before the crowds. If there will be crowds this afternoon—I don’t know.”

He had done a new painting the day of my visit, a true pink with a streak of white on the right side. “You see,” he said to me, “after we spoke my mood changed.” He picked it up from the table carefully, holding it by its edges, and carried it to the open door where the natural light was strong. Holding it to the light, his brown hand with its flat nails trembled.

The new painting came alive in the sunlight. It was pleasing, cheerful and tranquil.

Aaron asked if next we could see the graphic blue-and-gray paint- ing, which he had spotted on the table. The painter slowly made his way back to the table to fetch it and brought it to the doorway. With its higher contrast of values, in the bright daylight, it became more subtle.

“It was very calm,” he said, “the blue and the gray, and I decided it needed punch. I picked up a black pastel and zip! it had punch. But it’s a total risk enterprise. I could as easily have—zip!—spoiled it.”

Aaron went back to the tables to fetch the yellowish walnut ink painting, hoping, I suppose, to spare the painter the trip, though the

painter followed close behind him, and he dropped it in a clumsy move- ment. The painting fell facedown on another painting. Aaron flinched as it fell. “I’m so sorry,” he said quickly, reaching for it and holding it gently. “But these aren’t wet. Thank god they aren’t wet anymore.”

“They aren’t, no,” the painter said. He was displeased. He grabbed the painting from Aaron and hobbled to the door. Examining it closely in the light, he seemed to settle down, to find the strength to hide his irritation.

“From now on, let me do the handling,” he said.

Aaron bowed his head in apology, and then, realizing the old painter couldn’t see this gesture, said apologetically, “Yes, that’s best.”

The painter took up a blue painting. A velvety density of color gath- ered at the left, where the acrylic was thickest, and the middle faded to a lighter blue. On the right, a pearly pastel took over. Light blue washes like a thin watercolor stippled this portion, and in the sunlight, a faint pink iridescence rose up.

“The dots are like a consolation,” Aaron said. “Which dots?” the painter asked.

“Here, in the light, almost like glitter from beneath.”

“I can’t see that. It’s mysterious to me, what these paintings do.”

The two men stood in the sun. “How did you get this color?” Aaron asked.

“I worked acrylic into pastel, both wet. I don’t know exactly. I add, and the paintings change. This one was mostly purple at first.”

“It’s amazing how you hide the brushstrokes.”

“In the center the surface is so smooth,” I said, “and then the rough edge.”

“In the seventies,” the old painter said, “there was a bar on the Lower East Side where the artists hung out. We would talk about painting. This was when hard lines were what people were doing; they’d use masking tape to get those hard edges. And what people would ask would be, ‘Are you hard-edge or soft-edge?’ It used to be, ‘Are you figural or ab- stract?’ So this was the new question. And my friend came up with a

good answer.” He laid down the painting. “He would say,” and here he put his hands in the air and waved them maniacally, “‘I’m on edge!’”

“I’ve always been about showing the process. An art critic from the nineteenth century said that there were two kinds of painters: sun painters and moon painters. The sun painters showed the process. The moon painters erased it. Vermeer was a moon painter.”

He set the blue painting on an empty easel by the door. We all ex- amined it without speaking.

“Matisse would erase what he’d done each day. He’d paint all day and at the end of the day wipe the paint away so there was only a ghost image, and the next day he’d begin again. He has a painting called Pink Nude, a pink figure reclining. These lines behind.” He drew a grid in the air with his hand. “He worked on that painting for seven or eight months, and it looks like it was painted in an afternoon. New York magazine did a spread on it, showing the evolution of the painting.”

“Another moon painter,” I said. “Yes.”

“He’d have his assistant wipe the paintings, I heard,” Aaron said. “What a strange job, wiping away his work.”

The painter ignored him and addressed me: “The article talks about his sybaritic side, and it’s true: Matisse loved pleasure. His work has a deceptive ease. When you said the work shows in one painting of mine, that was an astute comment: the work should not show.”

“It’s hard to do,” I said.

“‘Profound and lucid sight,’ the critic says. That was the Pink Nude.” “Will you change this one now?” I asked.

“One painter I knew, he’d go in and rework his old paintings. He didn’t have very many, and he kept reworking them. He couldn’t ever stop. For me, once it’s finished, good or bad, it’s done. I don’t go back in and change it.”

We all fell silent, our eyes on the small blue painting, whose pink iridescence withdrew itself from us as the sun dimmed behind a cloud. “I’ll begin packing this afternoon,” the painter said to me. “I leave tomorrow on the train.”

“I’m happy to help,” Aaron said.

“Thank you,” the painter said. “I might need assistance carrying my valise back to the residence.”

He was growing tired. We thanked him for inviting us, and he thanked us for coming and walked us to the door. “You beat the crowds,” he said, “although I don’t know if there will be crowds.”

On my way out, I asked him, “What is that word? I couldn’t think of it. The word for overwork.”

“Oh,” he said, happy, “iberpotshke. Why? You want to use it?” “Perhaps.”

Aaron had gone ahead. I turned to go, and the painter reached out to delay me. “Remember, my dear,” he said gently, “for the abstract expressionists, there were two things: action and hesitation. And only one was worth something.”

As the painter waited in the residence lobby for a cab to the train, I came down to say goodbye. By his feet sat his battered brown suitcase. He held a black portfolio bag containing all the paintings he had done. He was taking them with him back to the city. I asked how he would store them. “Well, I have flat storage, and so on, archival boxes.”

He took from his bag a final painting he had made, a light gray painting. “There are a million different grays. Complementary colors make a gray: violet and yellow, for example.”

The painting had a muted, haunting quality. It reminded me of mist rising off the winter ocean. It was by far my favorite. I admired the subtle mottling and striations. Whether or not he knew it, they were beautiful. I told him so. He brought the painting up to his face. “Gee, I wish I could see that.”

I thought he might intend to give me this gray painting, but he took the painting back. His gesture was protective, a bit triumphant. He tucked it in his valise.

“What will you do when you get home?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I wish I could take the landscape and the air and the silence.”

“What is it like where you live?” he asked after a pause. “Is it turbu- lent where the two oceans meet or do they get along?”

“It’s hot,” I said, honestly. “Hot and strange.”

“Will you write to me?” he asked. “If I give you my address?” “Of course,” I said, though we both knew I wouldn’t.

He departed for his train, paintings in tow. I watched him make his way to the cab. He did not want help out, though I offered. “Write me,” he said again. I never did, and he never wrote me, either. But after he left I went to my room and looked up the article he had quoted, the one that praised Matisse’s profound and lucid sight. I read it often, and, when at last I began to write again, I pinned it over my desk. It was by Kay Larson. He had gotten the quote right. She herself was quoting a curator’s assessment. Of Matisse’s life, she writes: “At times he surges forward with a new idea, as the confusion of influences under which he has been laboring suddenly sorts itself out. At other times, he draws back and gathers his energy, a process that can take years or even decades. Sometimes, both states exist in the same moment, linked by the courage to dare even to fail.” “If you’re like me,” she adds, “this show will bring you to your knees.”