In summer especially, Julie thinks of her grandfather. She imagines him wheeling his bike out of the garage, the tires freshly resuscitated, ready to pedal up one street and down another, in search of things. Sometimes the things he found would be too large to fit inside his backpack, items that couldn’t be transported while also riding a bike, and he would ride back to the house to drop the bike off. He couldn’t drive, so he’d walk the route back—sometimes rolling their Radio Flyer behind him—to the painting left out on a curb, the ergonomic chair left next to the dumpster behind a CPA’s office. But mostly his treasures were small, or could be folded, rolled or otherwise made easily moveable. The snowglobe with a figure skater mid spiral inside of it. The rug that her mother, his daughter, had promptly thrown away again. A nearly perfect pewter tray.

His most fruitful days were the ones when house after house, an entire residential street, decided to hold garage sales on the same day. Boxes of CDs that usually lived in a corner of a basement, the legs of tables balancing on dry lawn grass, baby clothes folded atop them, kitschy cups too. He’d never learned to speak English with any kind of consistent comprehensibility, but a smile would appear wide under his baseball hat, and usually whatever coins he pulled from his pocket, whichever bills he’d offer, pulled free from his sandwich folded stack, would be enough.

He’d been diagnosed with cancer in the last week of June and thirty-six days later it was August and he was dead. That summer there were no treasures. When he’d started dying Julie and her twin sister Lucy made themselves scarce. Refusing to bear witness as his body anticipatorily emaciated itself meant it wouldn’t keep happening, but of course, sooner than anyone expected, it did. They were all there at his deathbed, the mattress their mother had bought for the living room once stairs became insurmountable. Julie, Lucy, their mother, their father, popo, and him, lucid until the end.

After he died, neighbors came, though their mother had never been particularly social with any of them. She would open the screen door, lean her body partially out, and nod. We loved him, the visitors would say. Yes, thank you, she would reply. For weeks, as more residents of the surrounding houses learned of his death, little notes of condolence would appear in their mailbox, once someone brought an actual casserole. Here, my special recipe, she said. Their mother had brought it in and set it on the kitchen counter in front of where Julie sat doing SAT prep. Julie rolled her pencil into the book’s gutter and slapped it shut, calling for her sister.

A casserole! Can you believe it? I don’t think I’ve ever eaten one before, she’d exclaimed, to which Lucy had replied, Wait, is lasagna a casserole? It is, isn’t it?

They had looked it up to find tepid internet consensus. Lasagna is indeed a kind of casserole.

Their mother cut into it that night. Inside, layers of sour cream, shredded chicken, some sort of sauce, and, Julie exclaimed, There’s potato chips in here!

They ate the casserole as a self-proclaimed adventurous traveler might eat pig brain. The primary source of enjoyment, the exhilaration felt when, relieved and a little bit smug, they finished the slices in front of them, Lucy finishing first, licking a clump of sour cream from her chopsticks with relish.

Their mother had stood up then, to stir fry some vegetables so the meal wouldn’t be entirely nothing.

That had happened three years before, his death, the casserole. Sometime during her spring semester Lucy had decided to stay with their father in Florida for the summer, working for him at his medical practice there. A college length summer break would be nearly five times longer than the longest stretch either of them had spent in the same house as him since he moved when they were thirteen.

But why? Julie had asked when Lucy told her on the phone during finals week.

I like the idea of making money off him, the sand, the surf, hearing the ocean from the window of his house by the beach, Lucy said.

Their father, and the sun, and the beach would sap Julie’s energy, she knew, constantly providing light that was too bright, sand that got everywhere and stayed.

No one but her roommate knew about the depression that had quickly and without warning, it seemed, sapped Julie’s energy. By the end of her second semester of college, rather than leave her bed to take the final exams for two of her courses, she had taken an incomplete in one and outright failed the other. But Julie had started ignoring her mother, answering—of dozens of calls—only those three times, which to her mother could only mean that Julie needed her, needed to hear that there was a place for her. At the very least there was always a place for a daughter with her mother.

Just come home, their mother told Julie over the phone in February, in April, in May as the semester was ending. You can just come home for the summer.

Which is how Julie came to be seated on the bright pink plastic stool she and Lucy had used their entire lives when washing their feet before bed, now kept in the basement surrounded by unlabeled cardboard boxes. Boxes no one had peered into since the top flaps had been folded down and taped up.

The night before, sitting on the couch with bowls of rice in their hands, two dishes of meat with vegetables on the coffee table in front of them, watching Dateline, Julie had asked about the boxes: When are you going to sort through the stuff in the basement?

When Julie told Lucy she would be home for the summer, Lucy had said, Maybe you can convince mom to finally look through all those boxes. Mom actually listens to you.

Their mother had been planning on putting the house up for sale, downsizing to a townhouse. She’d had this plan for a while, but always it would happen as soon as: as soon as your father comes back, as soon as you girls go off to school, as soon as I have the time.

You can’t take it all with you, Julie said, you have to at least look through it.

She was responded to with silence. Their mother often did this. Julie and Lucy never knew whether she’d heard them. Almost always she had.

In the morning, as she was leaving for work, she’d turned back, her hand on the knob of the door leading to the garage and said, You can do it, waving her hand in the direction of the basement door.

The first box Julie opens is filled with folded clothes. She takes out the top item and shakes it out, the motion revealing a seafoam green blazer. The stitching of one of the shoulder pads has loosened such that it dangles. It is the first item she tosses on the ground, on a small rug she’s placed on the ground, inaugurating this: the discard pile. The first few boxes go quickly. It is mostly clothing Julie decides that the full circling of trends will not normalize again. She saves a pair of high-waisted jeans for her sister, some patterned button-down shirts for herself. The discards pile up. She grabs a handful of plastic bags from upstairs, under the kitchen sink, unknots them and begins stuffing clothes into them.

She wonders if these clothes can be recycled somehow, the fabric unraveled back into individual strands, remade into something else. It’s probably more effort than it’s worth with so many clothes already in the world, with more new clothes being made each day from fresh fabric, virginal items. Most likely these clothes will just be relocated, unwanted, from one location to another. The seafoam blazer on the bottom of the pile is back on the top in the last plastic bag she fills, forcing her to think about it again for a moment, how the ugly blazer will stay forever in its current form, how its body will disintegrate hundreds, maybe thousands of years slower than hers, this gross green thing will outlive her. She feels sad for the blazer. To it she whispers, I never want to see you again. Then she moves the bags of clothes into the trunk of her and Lucy’s car.

◆

Popo had come to live with them first. She took an early retirement at the factory and arrived a few weeks after they were born. Gonggong had kept working, joining seven years later, when they were in second grade. After he moved in Julie resolved to become his favorite, since popo preferred Lucy. She said Lucy was tougher and, though Julie and Lucy were identical, cuter. It was not a physical attribute, being cute, having cuteness. She said Julie buried her face too deeply in books and cried too often. After Julie cut her hair short their sophomore year of high school, the first major change to their shared appearance that either twin would make, popo said, You look too much like your father.

It was gonggong who taught Julie and Lucy, after watching them tie their shoes, to tie their shoes a different way, more quickly. He taught them how to ride a bike. Julie would sit with him for hours and watch him tinker with the washing machine, the lawn mower, the car, a clock, until it worked. Together they would sit, him guiding her through the process of patiently and gently untangling cords that had somehow wrangled themselves into impossible positions.

Perhaps their mother and father had favorites too, but if they did, it was felt quietly, and anyway, they were at work too much of the time for it to be reflected in their behavior in any way that mattered. They were building a medical practice together in those years, their father was the doctor, and their mother did everything else.

When they were ten, their father fell in love with a pharmaceutical rep. Their mother was hurt by the banality of it all. The way he said about this pharmaceutical rep, We are in love. As though it was a word he used often, as though he had ever uttered the word love in reference to anyone else.

Their mother in those days would often laugh apropos of nothing, and then exclaim, He loves her!

He’s been ruined, their mother told them, by American culture.

When Julie and Lucy were thirteen, he had moved over a thousand miles away from Western New York to Northwest Florida to start a new medical practice. I can make more money, he’d said, Cardiologists are in demand there. On school holidays and some long weekends, they would fly to Florida and spend a few days with him.

Julie can’t remember exactly when or how she found out about the pharmaceutical rep, nor can she remember how she learned the pharmaceutical rep had moved to Florida too, or rather, with. But when they all visited, or just Lucy and Julie visited, the pharmaceutical rep would make herself scarce. Their mother continued managing the finances of the practice, and their household, and knew how much money he spent on the pharmaceutical rep, and she fumed about this more than about the love he was also apparently giving her.

He wanted a divorce, but refused to be the one to file for one, at least not while his parents were alive. Their mother refused to file for one either, because she didn’t want a divorce. It’s not like you love him, Lucy said to their mother once when they were sixteen, why not just let him go? This was the only time their mother slapped one of them, across the face, her hand reaching out as though automatically. You’re pathetic, Lucy had spit out, running to the front door, slamming it behind her. Their mother had crumpled onto the bottom stair, sobbing until she was out of tears, Julie rubbing her back rhythmically until popo, who had not understood any of the fight, came over to say, That’s enough crying. Then, with a final squeeze of her mother’s arm, Julie had gone to find Lucy.

◆

Lucy calls to tell Julie she had sex with a girl. I didn’t really like it though, she says. I mean, like, I liked it, but I didn’t really like it.

Uh huh, Julie says.

Lucy continues, It’s this girl who also works at Dad’s office, and she’s been eyeing me for the past couple weeks, and then last night we both got kinda drunk after work, and bam, ya know? It just happened.

Uh huh, Julie says.

And, you know how they say that, like, you haven’t had a real orgasm, not the really intense, earth-shattering kind, until you’ve had sex with a lesbian? But I don’t know, when I came, it was just okay, maybe because I just wasn’t that into it when I’d remember she was a girl? So it wasn’t life changing or anything.

Julie says nothing, and there is a brief pause before Lucy says, I’m glad I did it though.

That’s good, Julie says.

A few moments later, the call ends and their mother looks up from her bowl.

Lucy told me to tell you she says hi, Julie says.

She is good? their mother asks.

Yeah, she’s fine.

◆

The next day Julie looks through more boxes. The five boxes of clothing she looked through the day before made no difference, she thinks, as she looks at the rows of boxes still left, stacked all around the basement. She lifts two boxes onto the ping pong table and opens the top one to reveal cords and flip phones, batteries and two remote controls. The other is filled with battered children’s books, some of the spines have been squashed, contorted. She looks through them, taking in their covers, flipping through a few of them, trying to remember any of them. Had she read them? Had her sister? Were these books read to them? She can’t recall either of her parents ever reading to them, which is not to say that they never did, perhaps they did and it just hadn’t left an impression, a recollectable one anyway. If her parents had read to them, it must have left an impression on her brain somewhere, surely it would have, the way a baby’s brain develops slower and less joyfully if they’re not often spoken to, the way a baby is physically smaller if they are not cuddled. In any case, she decides, none of these books need to be kept.

A box full of loose papers, some binders, social studies written in block letters in black sharpie on the front of a bright orange one, two empty trapper keepers. Julie tries to imagine the inverse of this process, her mother at some point gathering things, packing them away, each box a layer of sediment, a collection from a different era of their lives. The next three boxes she opens are filled with old school handouts and quizzes, report cards, completed assignments, an unsigned permission slip that’s been wrinkled into near oblivion. She spends an entire afternoon looking through these papers. She can’t remember ever having such strong thoughts on Of Mice and Men, but she did, she must have, because here they are, written down. One of Julie’s AP Lit essays with an A circled on the front page contains a metaphor comparing the psyche of Frankenstein’s monster to the breaking apart of Pangaea. She reads the report now as though it were written by a stranger. On a stack of report cards spanning a dozen years, Lucy and Julie were both a pleasure to have in class. Julie got a C in chemistry sophomore year. I’m a chemist! Your mother is a chemist! their mother had exclaimed when she saw it, shaking her head and letting it fall onto the counter on top of the other mail.

Lucy had always gotten better grades in science and math, Julie in English and social studies, a dichotomy that felt perfect and too neat. You’re the humanities, and I’m STEM. Together we make up one well-rounded person, Lucy used to joke. It’s almost like we’re twins, Julie replied sometimes, completing the joke.

Julie would feel secretly pleased. Of the two of them, Lucy had been the one always more eager to assert her independence, be different. She did not like to be clumped, when their shared piano teacher referred to them as the girls, or a teacher called them the twins, whenever anyone suggested they dress up as the twins from The Shining for Halloween, it was Lucy who would correct them, offer up her name as though that person didn’t already know it, an assertion of her separate and distinct personality. It had felt like a betrayal to Julie at first, and even once they’d talked about it, once they’d grown old enough to have researched twin psychology and have opinions on it, Julie was more likely to see an article about twins separated at birth and meeting each other after thirty years to find that they’d chosen the same occupation or named their firstborn child the same fairly uncommon name, and show it to her sister.

It had not been until they were in high school that Julie began to suspect that the discomfort she felt around girls was not shyness or fear of their judgment, or not merely that, and it was not the same reason her sister said she preferred the company of boys, which was, blithely: I just get along better with guys. Less drama.

She doubted it, still, for a while after, sure that if she really were into girls, attracted to them in that way, she should have known, that she should have been asking for toy cars instead of Barbies as a child, that when she told her sister, Lucy would be able to say, I’ve known since we were five, you were always playing with toy cars instead of Barbies.

It was not until Julie finally kissed her second chair behind a parked car in Italy on one of the last nights of a three-week tour for the young people’s philharmonic, that she felt it. Relief. When she told her sister, breathlessly calling her that night, Lucy had been unexpectedly angry.

But I know everything about you, she said. But we’re sisters.

Almost immediately Lucy had sought to retract her words, erase them with I’m sorry, I was just caught off guard. But Julie was not upset by her sister’s reaction. Instead she’d felt an odd triumph, that something important had changed between them that night—and it was Lucy’s confidence that Julie would not, and could never, surprise her.

Julie is reading through Lucy’s response to a Wordsworth poem when she hears the garage door opening upstairs. She’s surrounded by papers, they’re fanned out around her and she can’t remember which aren’t sentimental. She’ll have to look through them again. It’ll be quicker when I do it tomorrow, she thinks, and goes upstairs to greet her mother.

◆

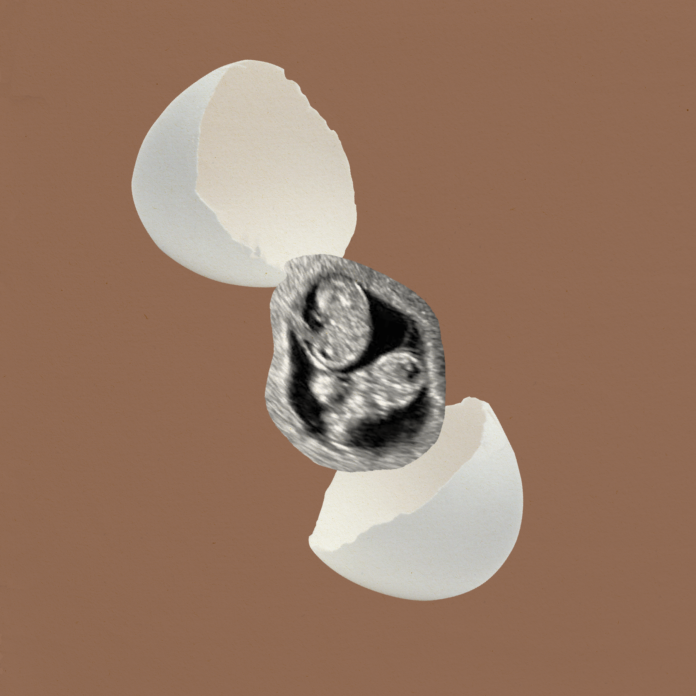

It’s on the fifth day of slowly cleaning the basement that she finds the picture. It’s in a box of junk, not unlike any of the other boxes of junk she has been looking through, but she instantly recognizes it for what it is. She’s reached the first of gonggong’s boxes, the boxes filled with his treasures. Here, the intricately carved wooden spoon he excitedly showed her after he bought it for five dollars, the stem of it featuring the body of a bear, a moose, trees, centered around the name of a town. After he brought it home she’d dialed up the computer to search the name, it was in Alaska. Next she’d looked up how to say Alaska in Mandarin. Here, a jewelry box. Julie opens its glass-fronted doors. She opens each compartment, finds them all empty. The whole thing is dusty. She is sitting with it in front of her, deciding what to do with it, fiddling with it, when the whole thing tips forward. She catches it in her lap and tilts it to look at the bottom, where one of its little claw legs has come off. She tries to screw it back in but it doesn’t fit in its hole, so thoroughly that she wonders how it ever did. When she gives up and uprights it, there is a photo face down in her lap. She flips it over and glances at it. It’s a woman. Beside her, a young boy, perhaps five years old. She doesn’t recognize either of them, but her extended family, on both sides, is large and diffuse. She has many relatives she wouldn’t be able to pick out in a line up and many more that she would be able to pick out, but then, if pressed further, would not be able to explain how exactly they were related. She puts the photo aside to ask her mother about later.

◆

That evening Julie is chewing and thinking, chewing and thinking, a recorded episode of 48 Hours playing on the TV before them, waiting for the commercial break that they only sometimes remember to fast forward through. When a commercial starts, abruptly flooding the room with its brighter lighting, neither Julie nor her mother makes a move for the remote control that sits on the cushion between them. One commercial passes, then another, before Julie reaches for it, and mutes the TV.

I found some of gonggong’s things in the basement today.

Her mother doesn’t say anything, but Julie can feel in the air that she has heard.

Julie continues, not glancing at her mother.

It was kinda cool, seeing some of it again, the junk he bought. I also found this photo with people I don’t recognize.

On the bookcase behind them are shelves of photo albums their mother had meticulously filled. She claimed to be able to remember taking every single photo of her daughters that filled them. It was Julie that pored over them, looking through the albums of her parents when they were young, before they’d gotten married, before they were parents. Neither of her parents had more than two photos of themselves as kids. Their photographed lives began in college, their slacks high waisted and glasses nearly octagonal. It always makes Julie feel a certain way to see those images, a mix of pleasure and pain like putting in her retainer at night after a week of not wearing it.

The commercial break ends, and Julie unmutes the television.

He definitely murdered her, her mother says.

The episode is about a couple who travelled to Mexico on a vacation meant to revive their troubled marriage. The wife went missing on day three and the husband flew back to the US, vowing to liaise with Mexican authorities and find out what had happened to the wife from the house where they had lived together in Ohio.

On the screen the husband was pleading with news cameras to find the wife, a recording of a recording.

Yeah, probably, Julie says.

Definitely, her mother replies, don’t you think?

Her hands move to Julie’s hair. She tucks the curtain of it behind Julie’s ear.

Are you my daughter? she asks.

Julie looks over, grinning. Their mother asks this often enough—her expression one facial wrinkle away from true sadness—that it has become a running joke between Julie and Lucy, one that they had not let their mother in on. Are you my sister? they ask each other sometimes when they see each other again after being apart, or when in high school they would have separate plans with friends and would run into each other in the bulk candy aisle of the grocery store, stocking up.

Who else would I be? Julie asks, moving closer and putting her head in her mother’s lap. Her mother fingers her hair, twisting and untwisting a clump of the strands. She used to braid Julie and Lucy’s hair every morning when they were young, before waking up for school became a struggle, making mornings hectic.

Julie looks up at her mother’s face, sees it softening, and she feels a sudden urge to touch her mother’s cheek, to trace it, to really look at it, study it as if it is foreign. She can see new wrinkles. It’s beginning, her turn to watch her mother’s face change, too quickly, such that maybe someday she will look at the old woman her mother has become and wish for the younger, stronger mother she is lying on in this moment, the recognizable mother.

Julie pulls the photograph from her back pocket, and looks at it again before pushing it up at her mother’s face.

Do you know these people?

Her mother takes the photograph and studies it, continually twisting and untwisting the same clump of Julie’s hair.

No.

She hands the photo back, looks up at the TV again and says, We have to rewind.

Julie calls her sister to tell her about the photograph: It’s got to be important, right? It’s the only thing that he kept in there.

You could ask popo about it, Lucy replies.

How do you suggest I do that? Call her and then what? Describe this picture to her? I mean, I guess I could always send the photo to yima over wechat and see if she recognizes them.

What makes you think that yima would recognize them if mom doesn’t?

I don’t know, maybe because she stayed in China or whatever.

When was the last time you messaged yima?

Lunar New Year.

That’d be so random, then. To just message her out of the blue with this random photograph.

Yeah, I guess.

Sometimes Julie wonders if yima resents the fact that their grandparents, who knew no one was happy, had chosen to stay there, in America, by their mother’s side long after Julie and Lucy could look after themselves in the hours after school. It had spared their aunt in some ways, she’d never had to change their grandfather’s feeding tubes the way their mother had, but her visa application was denied, and so she never got to say goodbye either.

They are both quiet for a moment before Lucy says, God, do you remember the fights popo and gonggong used to get into?

You make it sound like they fought all the time, Julie answers. They didn’t get into that many fights.

Are you kidding me? They were always fighting. Remember that time popo chased him around with that huge rusty sword he’d bought? What were they even fighting about that time? Do you remember?

Lucy’s voice is lighthearted, hinting at impending laughter, but Julie’s voice is sharp when she replies, I don’t remember that ever happening.

You’re kidding. That shit was epic. You’ll probably find that sword if you keep cleaning out the basement. Maybe it’ll jog your memory.

It was true they had fought, Julie thinks, after they’ve hung up. Though mostly it had been their grandmother yelling and their grandfather staying silent, which infuriated her further. Their mother hated it. She’d say, Ma, you’ve been married for so many years. You’re already so old. What is there to keep fighting about? You’ve already reached old age. Aren’t you embarrassed to be screaming like this?

Even after all their fights, when gonggong was on his deathbed, in his last moments, they’d promised each other they would marry in their next life too. Julie found it vaguely romantic, which Lucy found as repulsive as the promise itself.

◆

Julie is still thinking of the picture as she lies in bed a few nights later. The basement is cleaner. Her phone buzzes. It’s Lucy. She thinks for a moment about not answering.

Hey, she says, bringing the phone to her ear.

Lucy’s voice is hard and angry, the words enunciated so that there can be no mistake as she says, She’s pregnant. She’s fucking pregnant.

Who? Julie asks. For a moment she thinks her sister means the woman she had slept with.

That woman. That bitch. Dad’s, Lucy’s voice stops abruptly, and Julie hears her take a deep breath before saying again, She’s pregnant.

What? Julie feels her stomach turn over. How do you know? Did you meet her?

No, of course not, Lucy says. Dad didn’t even have the fucking balls to tell me. I read his texts.

Oh. How do you know his password…nevermind. He was probably going to tell us.

Julie, you’re so naive. God, Mom and Dad are still married. This is all so fucked up.

Julie stares up at the blank night sky through the skylight above her bed. It feels like staring into the void, this black square. She tries to imagine their father and this faceless woman who has hovered over their lives for years, and a little baby. She feels slightly sick to her stomach when she imagines the baby as a girl, perfect, department store catalog cute. Then she wishes she could slap herself out of having felt that inane jealousy. Her sister is still talking.

I can’t be around him anymore, she’s saying.

Does he know that you know?

No. I left the house. I’ll go back later after he’s asleep.

Just come back here. Just come home.

◆

The next morning, Julie decides to watch as her mother eats breakfast. Starting from when I glance up, I will look at my mother and see her as my father sees her, she is thinking, as she spoons her own oatmeal into her mouth.

It had become difficult for Julie to see her mother, the person, the woman. What does her face look like, divorced from affection, devoid of love’s projections? Julie had grown, in the last few years, so used to seeing her mother almost as a living martyr. Even when Julie or Lucy confront her sometimes, challenging some of her insights into the human condition, it’s hard not to see the mother whose sacrifices had built her. There are parts of her Julie does not like, of course. Julie had told her mother once that it was more likely that she’d marry a woman not a man, though even that was a concession, but had immediately passed it off as a joke, before her mother had time to react. A friend of Julie’s from middle school, who had always gotten better grades than her, and whom her mother liked a lot as a result, had gone to college for a semester and then dropped out to move to Las Vegas and play League of Legends professionally, and when Julie showed her mother the picture of them, their septum newly pierced, lifting their shirt up slightly to reveal on their stomach a slightly-bloody still tattoo inspired by an Edward Hopper painting, her mother had begun to tear up. It’s not like they died, Julie had snapped, pulling her phone back, pressing the side button to blacken the screen. What a waste, her mother had said, I wish you hadn’t shown me that picture.

How am I going to tell her about this, Julie looks at her mother and wonders.

◆

Her father calls Julie that afternoon, while she’s in the basement.

Lucy is gone. Do you know anything about this? he asks.

Julie almost says, No. She almost says that she doesn’t know anything. Instead she doesn’t say either of those things, instead she says—and it surprises her when her voice says this, and for a moment she thinks she can take it back, that she actually only imagined saying it and didn’t actually say it.We know she’s pregnant.

After she says this, she is silent. On the other end of the line, her father is silent too. They’re both silent, until Julie decides she doesn’t want to do this anymore, this being silent at each other, and moves her phone to hang up, but then, surprising herself again, she doesn’t. She brings her phone back up to her face, and says, How could you do this?

She doesn’t know exactly what she means by “this.” Ruin the equilibrium they’ve created? She wonders what will actually change when this baby is born. Her parents are still married on paper only, and is it really such a big deal that another person is being brought into the world that shares genetic material with her but whom she will likely barely know? These thoughts flit through her mind, but they do nothing to quell her indignation, the pain it is hiding. He still hasn’t said anything, so she repeats, How could you do this? She hears the waver in her own voice, its inconsistency, the way it rises and falls as though she can’t control it.

You think I wanted this? His voice on the other end is quiet, his words lash out and hit her.

Again it is unclear to Julie what “this” means. His “this” certainly has a different meaning than hers. Does he mean this baby? For a moment she feels pity gurgle in her stomach for this unborn child, but almost immediately it is consumed by a larger wave, her own anger, for herself, for her sister, for her mother. She has never uttered harsh words to him before, only thought them, for the past several years regarding him, each time she’s seen him, with a mix of disgust and sadness, a little nostalgia. But now with him on the phone, unable to see his physical form—the one that had woken her up each morning for school, flicking the lights on in her room, his body leaned against her door frame the first thing she saw most weekdays of her childhood—she feels brave. The tears that had been so close to spilling over evaporate still in her eyes. She will not cry with him here. It would change nothing. She imagines her father probably feels nothing, would not have been affected by her tears. Julie clears her throat.

You are a bad father, she says. Her words are strong now, loud and bold. She feels proud of them, and in her pride, she also feels venomous. Gonggong was a better father to us than you ever were.

The extra words leave her mouth, and for a moment she wishes she could see them hit their target. They are silent again for a long stretch, and as neither of them says anything more and the moments stretch on, her thoughts lose their grip on her, and pass away. There is so much to say that there is nothing to say.

Do you know why your gonggong waited so long to join us in the US?

This conversation has been surprising enough so far that Julie almost doesn’t register surprise as this question catches her off guard. She could have replied that it was because he had to keep working, that he couldn’t retire early, or didn’t want to. Instead she asks, Why?

After your popo left and moved in with us, your gonggong moved in with another woman. They might have even had a kid, I think. But your popo wouldn’t let him off the hook. Eventually your aunt bought him a flight and shamed him into getting on it. You may think your gonggong was the ideal man, but—

Julie hangs up.

She tilts forward off the stool onto her hands and knees, curls into the fetal position on the discard rug and lies there for a long while.

Because Julie eventually falls asleep there, she doesn’t hear Lucy as she comes home, pulling her two suitcases from the trunk of the airport taxi and lugging them up the driveway. If Julie had been awake, she would have heard Lucy slam the door, she would have heard their mother come home from the lab where she works to find Lucy sitting on the couch watching TV. She would have heard Lucy tell their mother, Julie and I are getting a sibling. Instead, Julie only hears their mother drop her food container. The reinforced glass clanging on the floor wakes her up.

By the time she comes up the stairs, their mother is on the floor. Lucy is standing over their mother’s hunched over, squatting body. Julie looks at her sister, who looks like her, who also looks so much like her own person. She remembers the two nights they’d overlapped at home after the semester ended, before Lucy left for Florida. How Lucy had bought an at-home wax kit, determined to have the hair-free crotch of a child. She hadn’t read the directions clearly, putting all the wax on and letting it all harden, until the entire area was encased in a helmet that she’d been too scared to rip off. Julie had been called in, frantically, and it was as she was cutting the wax from her sister’s pubic hair, staring deeply at the landscape of her twin vagina, that a most acute feeling had washed over her, that we can know someone as well as it is possible to know a person, and still question how much it’s possible to know or be known to anyone, including yourself.

Before their mother can straighten up and see her, Julie runs up to her room to grab the picture and the jewelry box that had housed it. She looks at the picture again. If there had been a child, this must be him, this boy. No sister who will know him, no father who will stay with him, no basement full of junk to claim. She tucks the woman and her son back into the jewelry box, places it inside her closet, and shuts them inside. Then she goes back downstairs. Lucy and their mother are both on the floor now, their bodies entwined around each other. Julie looks down to see an uneaten hard-boiled egg from their mother’s lunch resting at her feet.