Life is pretty good now that it’s just Roadkill and me. There’s no school, for one—just the hollowed-out building with the doors wearing tatters of Christmas wrapping paper from the decorating contest. The winning class was supposed to get a pizza party. We miss pizza. Once we found pizza-flavored Pringles and ate them slow, letting the potato mush collect in our cheeks and ooze between our teeth like cheese, which is another thing we miss, opening our mouths to show each other the precious slime.

With school out forever, we get the playground to ourselves. I win every tetherball game against no one, punching the yellow ball back and forth until I really start whaling, throwing my fist against the dingy skin until it strangles the pole. I imagine the faces of kids I knew, kids I hated because they hated me. I think motherfucker and annihilate Nathan Ferris’s leathery head, pop his skull into the bruising sky. Eventually, it gets too dark to see. Roadkill keeps her distance. She dawdles on the seesaw, her ass planted on the asphalt because there is no one left on the planet to sit on the other side.

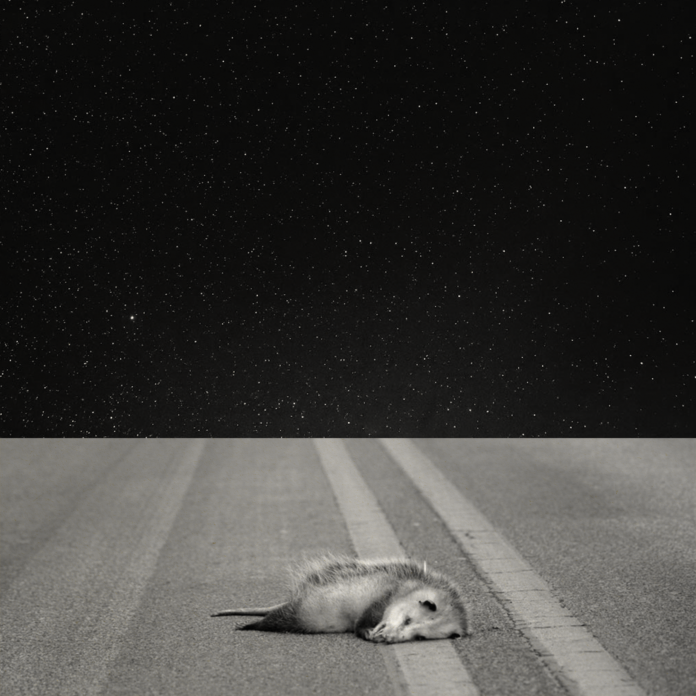

I call her Roadkill because when I found her, she was eating roadkill and looked like roadkill. She was still in her old house, two doors down from where I was holing up. I’d left my own place as soon as everything evaporated and I’d understood that I was free, like I’d always wanted—except I’d always thought that I would be the one gone, and the others left to whirligig around. I was doing the usual, going door to door for expired crackers and soup, when I saw her: a crumpled shape in front of the fireplace, turning over a flattened rat she’d impaled on a poker. The singed fur smelled rank and darkly sweet; shreds of flesh quivered over the lapping flame. She watched me with black eyes and an open gash of mouth, black hair mushed on top of a gaunt, imp face. Something fell from the rodent and popped in the fire. “Mine,” she rasped.

Since then, we haven’t met anyone else. I’m not sure if this is a mistake—if I’m in her world, or she’s in mine. We don’t talk about the people who are gone. Roadkill comes in handy, though. She can reach things I can’t. She can carry a heavy backpack. She can burp the alphabet and fling bricks through windows and stitch skin back together, even if the work is clumsy.

We ditched her dead address and moved to a nice part of town. Now we stay in a brick mansion with white columns running across the porch, lashed by ivy. Inside, the furniture is heavy and gleaming, like sleeping beasts. There are paintings of nothing on the wall and sculptures of horrid shapes, and a desiccated Christmas tree sagging with silver bows and ornaments. The presents: a bike helmet, a watch, a face cream, a pair of fur-lined boots, a box set of glasses, a flute.

My room belonged to a boy who was a little bigger than me; I wear his pants rolled up, and his shirts hang almost to my knees. I read his comics and probe his vintage camera collection.

I’m peering through the lens of one when Roadkill shoves open the door. She’s holding something in her hand and saying, “You want to explain this?”

“What is that?”

“You tell me, dipshit. I found it in the gutter out front.”

Then she becomes very still, the way she does when she expects something bad to happen. Her body goes so quiet, it’s like she disappears, even though I’m still looking at the husk of her. On her outstretched palm is a tin can.

“That’s a can of dog food.”

“It used to be a can of dog food. Now it’s empty. So either you ate it, or that stupid dog did.”

“What dog?”

Her eyes and lips grow narrow and dangerous. “You know what dog. Skinny, black. It’s been coming ‘round here, and now I know why.”

In my head it becomes a kind of name: Skinny, Black. You can see each rib, every furrow. On its back is a bloody patch of skin, alive with maggots. “I don’t know what you’re talking about. You’re just bored. Bored and crazy.”

She throws the can at me, but I dodge, and it clatters against the dresser. “We’re leaving tomorrow.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m bored, remember?” She grins. “Bored and crazy.”

I raise the camera, focus on her face, and press the shutter. If you go back to the house, it’s probably still hanging from the bedpost, her translucent likeness trapped on the coiled negative.

Hope gets you hurt. In the beginning, when we hadn’t explored the boundaries of our solitude, we would hear voices. Roadkill, who was clawing potatoes out of the ground, sprung onto her feet with her hands gnarled and loamy. “Jessie?” she said in a low voice. Then, more frantic: “Jessie!” She exploded across the yard, a blur that entered the tool shed and disappeared with a clatter and a shriek, and in a moment re-emerged with a nail plunged deep into her bleeding palm. I pried it out as she howled, as she realized that what she’d heard was nothing at all, just a phantom wind swirling lonelily out of herself.

◆

Another perk: now there’s no one to tell us we can’t drive. We roam until we find a car with the keys left glinting in the ignition, the owner vanished with everybody else. Roadkill slides into the driver’s seat and scoots forward to reach the gas pedal, coaxes the engine awake. There’s a rosary hanging from the rearview mirror and crumpled receipts in the cup holder. I smooth one out in my lap: beef jerky and Tylenol, purchased five months ago. I crunch the slip of paper into as small of a ball as I can muster.

Roadkill is a terror on the road. We weave around abandoned cars, lurch onto the curb, clip bumpers and amputate side mirrors. She laughs as the car clunks over a series of potholes. I stick my head out of the window, spraying vomit on the side of the car. I try to glare at her, scowl with my sour mouth, but her eyes are clenched shut with glee.

“Can you just pick a place already?” I say. Houses smear across our windows.

“O-kay-y,” she says in a singsong voice, and tears up the freeway onramp. She merges into the frozen traffic, then skates from lane to lane. We pass sun-worn billboards and accidents, monuments of deformed metal and exploded glass. We pass the next city, then the next. From here, it’s almost like nothing’s changed: storage warehouses with their metal mouths clamped shut, houses listing on weed-pocked plots of dirt, cars lined up in fast food drive-throughs like beads on a string, the funhouse windows of office buildings warping the clouds. This is the furthest we’ve ever gone. I look at Roadkill, but she keeps her eyes trained on the road, her expression another blank facade.

“Where are we going?” My voice cracks.

“What difference does it make?” she says. “Anywhere we go will be the middle of nowhere.”

“That’s not true. That wassomewhere.” I don’t dare say home, though the word is in my mouth, round and humid.

“You’re such a sissy.”

“Don’t call me that.”

“Why not? It’s true. Sissy,” she sneers, her face pinched and mean.

“I said don’t call me that!” I punch her arm. The sound it makes is clean and decisive.

“See? You even punch like a sissy.”

“Liar. You know that hurt.” I hit her again, and the car swerves. “How’s that?” I throttle her arm, her leg, propelled by a hallucinatory hatred. “Is that a sissy punch?” But she makes no further sound or movement, just drives as though I don’t exist, which makes me roar with anger, kicking the glove compartment until it pops open and releases a stream of papers into my lap, all of which I heave out the window. They flee like a flock of startled birds.

I slump into the seat, knuckles singing. “I hate you,” I tell her. “I fucking hate you.”

There’s not much to miss about it, but it was still my house, its dark windows like dreaming eyes. Inside, a persistent rodent smell burrowed under the sea breeze scent my mother sprayed to make it feel like we were on vacation, like we lived somewhere else. The thin carpet revealed by the glitching light of the TV. The chittering cat drifting up and down the stairs. It was a place I dreaded, avoided as long as I could by sitting on the bridge after school and waiting for trains to shudder underneath. I think about the house until something in my chest grows impossibly thin and painfully taut. Then I must fall asleep because later, I wake up, and the windows are squares of ink, and Roadkill is still driving.

◆

The car runs out of gas in the woods. We get out and stretch our legs, squawking at the sensation.

I urinate facing the emaciated trees and notice the green beginnings on their frail branches. The sun sharpens each silhouette but barely gives off any warmth. Roadkill squats in the middle of the highway and darkens the asphalt with her pee.

“It’s spring,” I tell her.

“Don’t watch me pee, pervert.”

There aren’t any cars on this stretch of highway, so we start walking. We haven’t had anything to eat or drink in hours and hours, but we don’t mention it. We don’t talk about problems that we can’t solve. Roadkill practices whistling and skips along the white dashes. Her hair has grown long and bounces against her shoulders. She is utterly unfathomable, her insides a black wind encircling a distant star.

“What’re you thinking about?” I ask.

She doesn’t falter, just looks at me sidelong as she prances forward.

“You never tell me what you’re thinking.”

“I’m not thinking.”

I see the penumbra of a bruise on her upper arm and feel angry and sorry at the same time.

“Fine, whatever.” I hop onto the next strip of white paint, and she crashes against my back.

“Hey, idiot, get out of my way.” She tries to shove me aside, but I grind my feet into the ground.

“You don’t own the road. I can walk wherever I want.”

“You’re just doing it ‘cause I’m doing it, and you’re obsessed with me. You’re in love with me.”

We jostle forward. “You wish,” I hoot. “I wouldn’t love you if you were the last person on earth. Which you are.”

Roadkill breaks into a sprint, arrowing down the broken line, then weaving in and out of the fragments. When she stops at a distance, she bends over and braces her hands against her knees. She waits for me to catch up and when I’m within earshot, she huffs, “I know you’re not in love with me, stupid. You don’t even like girls.” It’s a staggering pronouncement. The road between us telescopes open, stretching the white lines into thin ribbons. Somehow, I’m still walking. When I get close enough to see her heaving chest, she takes off again.

◆

Here’s what I think about: four chicken nuggets on a styrofoam lunch tray and a crust of dried ketchup on the diamond-pattern picnic table. Sweat caught in the crease of my elbows. Sun so bright it obliterates the neighborhood, ignites the lambent edges of clouds. The pledge of allegiance, which I only mouth. The resonant pong of a rubber ball hitting a fleshy calf. A trail of ants dissecting a dead beetle and the way the line disintegrates when I blow on it, hard. The whistle and chug of the train passing the schoolyard as it continues its mysterious endeavor. The boxcars rumbling under my swinging legs, the empty beer cans strewn on the platform under the bridge where I huddle. The hooded faces of roving teens passing joints in the park, their mouths rich with smoke. One of them so beautiful that it’s bewildering to look at him; his long mouth turns my insides to smoke. I think I can tell which houses on our street have the TV on by the quality of their silence. Our cat in the window waving her magnanimous tail. My mother asleep on the couch right where I left her, her breath rattling in her slack, open mouth. My mother shuffling papers around in search of the keys, late for another shift at a job she won’t keep. My mother in the garden with a cleaver, screaming at a possum whose face, sullen and tapered, is not so different from her own.

◆

Eventually, we find another car that starts. This one has an unopened bottle of Gatorade and a clattering tin of almonds in the center console, and these we suck down with naked desperation. After our brief glut, we are exuberant. We open the windows and let the brisk wind scrape us clean, whittle us down to yipping beasts as Roadkill thrashes the road, delivering us into a red-tinted world where danger doesn’t exist because safety doesn’t either. Here, we intuit, even the concept of death is annihilated. All along, unbeknownst to anyone, a third option has existed: you can simply go away, excised from the mortal coil. We scream, at the top of our lungs, the names of places we’re passing, each one stranger and more hysterical than the last.

◆

The skeletal weave of the woods gives way to swelling hills, then plains of flickering grass. We pass an enclosure where horses stampede in jagged confusion like ants that have lost their way. Scattered shacks coalesce into patchwork towns that morph into polished suburbs. I’m dozing again when Roadkill wrenches the wheel, slamming my head against the window, and takes us off the highway.

“Next time, I’m driving,” I snarl.

Roadkill says nothing. She scans the road, cruising at a surprisingly respectable speed.

“What are you looking for? Hey, you think we can go to the mall? I need new shoes. These reek.” I wait, then wave my hand in front of her face. “Hello? Anyone home?” When she still doesn’t answer, I clamp my palms over her eyes.

“What the fuck!” she screeches, prying my hands off. She turns to me with her mouth weighted with disgust. “You never do that again, do you understand?” A second before we smash into a lamppost, Roadkill corrects the wheel and pulls into a gas station.

Roadkill opens the car door, then kicks it out of the way and slides out of the seat. She slams it behind her. That’s when I see it: the slick of red on the gray leather upholstery. I don’t have any words for it, but something inside me turns in slow motion like a crag of rock in space.

◆

The gas station inventory is pristine. We pile the car with jugs of water, energy drinks, potato chips, cookies, cinnamon buns, beef jerky, canned soup. I put on a pair of sunglasses with marijuana leaves on the holographic lenses. At the last moment, Roadkill retrieves something from the store and stows the brown paper bag by her feet. Because we don’t talk about it, it resounds like a bell: the sustained phantom tone fills the car until we pull into the driveway of the house she has chosen, a bungalow with white siding and a wreath of fake pine needles and berries on the door. When I follow her in, I see the dark stain on the seat of her pants.

The light is almost gone. We fumble through the unfamiliar rooms until we find flashlights in a desk drawer. Our separate beams search the murk like unending, luminous limbs, groping the wooden floorboards and the pictures hung on the wall. The house belonged to a Latino family. Our palms of light pause on their faces: a thin-lipped man, a long-nosed woman, two big-eared boys, a square-jawed dog. Without saying goodnight, Roadkill and I disappear into bedrooms at opposite ends of a corridor.

I sit on the twin bed, shrouded in the permissive dark. The orb of light reveals a bulging hamper and a writing desk, the chair askew and draped with a plaid backpack, half unzipped. Crinkled galaxy and rocket ship posters cling to the walls. Loose socks punctuate the carpet. There’s an empty glass on the nightstand, a red alarm clock, a hardback book with green, slouching aliens on the cover. I pick it up, rake through a layer of dust with my fingers. Flipping through the pages, I find a piece of paper folded in the binding.

It’s a page ripped out of a magazine. In it, a naked woman sprawls on a bed of mussed sheets, her glossy legs open, one hand coyly caressing the vivid pinkness there. She’s nibbling the finger of her other hand, and her blue eyes, heavy-lidded and spiked with lashes, look right at me. Blonde hair spirals over her shoulders and grazes the top of her breasts, which overflow from a neat torso, so swollen they must make her ache, as I ache. I settle back against the pillows, positioning my body like hers, legs pried apart by a thrumming desire. I reach down and clutch myself, summoning first pale wisps of pleasure, then rolling, muscular waves that unfurl my body like the outspread highway and its pulsing white lines, stripping me clean of skin and tendon and bone until finally, with juddering breath, I spiral out its bounds completely, all ecstatic heat and relentless speed.

◆

Shame gives the next few days a kind of yellow-green tint. I can’t talk about what’s happened to Roadkill, so I leave her curled on the couch with a fantasy novel to go on lustful prowls of the neighborhood. I find magazines, posters, calendars, catalogues. I rut, lonesome and rapturous, in beds, on couches, in front of mirrors, seeping into the carpet. Naked from the waist down, I bounce on a backyard trampoline and listen to the springs talk. When I go back, I bring my slim findings as an alibi: a can of spam, a tin of sardines.

One night, I fall asleep and come to shivering on top of the covers in a strange bed. The early morning sky is the non-color of departed blue. I pull on my parka and stagger onto the street, pausing to remember how I got here. Birdsong embroiders the air. A thin mist sways in the air like a curtain, rustled by the two deer that gingerly lower their heads to the grass, keeping their eyes, brimming with darkness, trained on me.

When I return to the house, I’m surprised to find Roadkill awake. She sits in front of the TV as though she’s been watching the black screen and turns her head when I come through the door, eyes flickering and cheeks pink. She grins widely, stretching her chapped lips, and says “Welcome back” in a distended, waterlogged voice. Then I see the bottle she’s clutching in her lap. The brown liquid sloshes as she rises to her knees, then wobbles to her feet. “What did you find? Anything good?”

“No, nothing.” Realizing my mistake too late, I take my hands out of my pockets and expose the bereft palms.

“Then what,” she says, lurching forward, “were you doing all night?”

I shrug. “I got tired. I fell asleep.”

A peal of laughter splits the room, but it doesn’t seem to come from Roadkill. Her face barely changes; just the corners of her mouth twitch. “You always sleep like a baby. It’s fine, anyway. We have everything we need right here.” To demonstrate, she tilts the bottle into her mouth. Swallowing, she tries to set it down on the coffee table, but it bounces off the tabletop, bubbling into the rug.

I’ve never seen Roadkill like this. Even in a frenzy, she’s in control. I sense, through the slathered contempt, fear running like voltage through her body. I recognize it because I feel it, too: a current of unease and vulnerability that can’t be extinguished unless I smother it all—trust, loyalty, tenderness, love. But whatever’s she’s drunk drones loudly enough to blot everything out, leaving only a hammering anger.

“Look who’s here,” she says, pointing her bleary eyes behind me.

I turn around, realizing that the front door is still open. Standing at the threshold is a skeletal dog, its brindled coat clinging to emaciated haunches. It takes me a moment to understand that it’s the dog in the family portrait.

“You really can’t control yourself, can you?”

“I didn’t—This is the first time I’ve seen him, I swear.”

Roadkill narrows her eyes. “You’re pathetic. You’re weak. You still don’t get it, don’t you? Nothing here is real! Anything, at any time, can and will vanish!” Flecks of spit spring from her lips. She plunges her hands into the pockets of her quilted coat, jingling the keys. “I’m getting out of here,” she says, and barrels past me.

“Where are you going?” I rush after her to the car parked in the driveway, barely registering the dog slinking alongside my legs. I open the passenger door as she slides into the driver’s seat. Just as I get in and pull it closed, the car hurtles backward, slamming into the mailbox and bouncing over the curb. Roadkill straightens out the wheel and pauses. It’s the dog, standing in the middle of the road, starved into a barely recognizable shape, like a mangled drawing of a dog.

Roadkill punches the horn, but the dog doesn’t move. She flashes the headlights, screams through the windshield, lunges forward a few feet. The dog doesn’t move.

“Okay, you bastard,” she hisses. Then she goes quiet in that unsettling way.

“Roadkill,” I say warily. “Come on. Don’t do this. Let’s just go the other way. Please, let’s go the other way.”

Words I don’t hear keep filling my mouth like desperate prayer. I don’t know how long the car putters in the middle of the road before Roadkill grits her teeth and slams on the gas pedal, launching us across the precious distance, metal and meat colliding like the thunderous clap of God’s hand.

◆

Roadkill cuts the ignition and slumps over the wheel. I sit in the gyre of her howling, watching her white breath fill the car until the windows become mercifully fogged. Then I step out, careful not to look. I open the driver’s side door and coax her limp body into my arms. Together, we shuffle back inside the house.

On the couch, Roadkill cries herself to sleep with her head in my lap. My eyes close, too. They open again to see her bloated face studying the family portrait on the wall. I gaze at their smiling, airbrushed faces, the dog’s eyes like two fragments of amber.

“I’m sorry,” she croaks.

“It’s okay,” I say. “It went quick.” I snap my fingers but regret the meager sound. It’s the sound of an instant, which is enough to kill a dog, enough to annihilate everyone we know.

Roadkill is silent for so long that I think she’s fallen asleep again, but when I look down her eyes are wide, pink, pooled with tears. The pupils move toward me. “I’m a woman now,” she says. “At least, I think that’s what the bleeding means.”

I nod.

“It’s too bad for the species that we’re the only two people left,” she says. “They couldn’t have chosen two worse humans to start over with.”

“We’re not bad people. We’re just people.” It’s something I heard through the closed door to my parents’ bedroom. I don’t remember the words until I conjure them, but it seems to reassure her because Roadkill raises her matted head and works herself upright. Her crusted eye connects with mine, looming so large in my field of vision that it seems to be the one that speaks next.

“Have you ever been kissed?”

I shake my head.

“Me neither.”

We each take in the unknowable other. From a faraway perspective, we’re indistinguishable—as alike as any two blades of grass. But from here, terrifying individuality. She leans in. Our lips touch. It’s not like in the movies. Nothing leaps within me, and no choir billows in song. But still, there’s the ordinary magic of two humans making contact: flesh reassuring flesh, wetness mingling with wetness, brief heat and pressure combining to erase the rest of the world outside.