I’m writing these words from a spacious, well-lit, near-empty room. The nine hours I spend here every day are perfectly silent, save for the chirping of birds and brief, measured racket during recess at the elementary school next door. I attended that school 30 years ago, and 30 years prior to that it was attended by my father, whose home I’m in right now. I’m here to write. I’ve spent years in other lines of work with a varying degree of literary affinity, the last five in a completely unrelated field. That entire time, my desire to write remained inextricably linked to this space, like the layout of a familiar house blurrily imagined as the setting for any book we’ve ever read. Even when it was unclear what I would write about, when I would write it, or even to what end, it was a given that I would do so here. I do not question that premise now, either.

Taking the ultimate individualistic step in the home of one’s father may not seem like an obvious choice, but it was to me. His apartment on Lipsky Street is famous for the ascetic peace that envelops it. No television, no internet, no furniture to speak of, this apartment and the lifestyle it represents have always been a coveted goal for me, a lost paradise. This is where I studied for the SATs and university finals, and, since then, fled occasionally to write. If there was anything nostalgic about my choice to return here, it was nostalgia for my old self. But what I really sought to do in Dad’s place was to find some peace and quiet and to disconnect, which I insinuated to him as a condition for my arrival.

Dad, for his part, enticed me in his own unique way. During my final days at an office job, he texted me photos of the study I’m now sitting in. “The Lipsky Foundation prepares for a writer’s residency,” was the caption on one of them. That’s always been his way of communicating with me: adopting my language and my world for the purpose of a shared joke. In fourth grade, when I played soccer in the Maccabi Tel Aviv youth team and was forced to transfer from a downtown field to the one on the university campus, he pasted a new headline he’d made at a printer’s over an article in the sports supplement: “Fine Transfers from Maccabi South to Maccabi North for 350,000 Shekels”; when I worked night shifts as a news editor, he left me a 50 shekel note on the dining table, which he referred to as “taxi voucher from the producer”; when I started writing and applying for grants and fellowships, he gave me a check on my birthday, signed by the “Lipsky Fine Literature Foundation”. Now the foundation was offering me its assistance once more.

I’ve been coming to this study every day. Now I see this room—and me inside of it—for what it is, without the aura of longing. In honor of my return, I blocked Facebook and Twitter on my laptop and bought a small, outdated cell phone that liberated me from the dull, frantic buzz of the smartphone. My one remaining escape, therefore, is the wall my desk is set against. Out of cheerful nihilism and practical indolence, my dad has never seriously repainted this wall in the 20 years he’s lived here, thus allowing it to transform into a sort of family palimpsest. When I got here I found it decorated with unframed paintings made by my grandfather, my father’s father, the forgotten lyrical abstractionist Arie Leon Fine; between the paintings were nails affixed years ago, and tiny mortar burrows in the place of nails that had been torn out—both vestiges of the tall bookcase used by my father’s uncle, Israel Prize-winning essayist Yeshayahu (Shayke) Avrech.

Two very different people are intimated by the wall before me. Leon painted abstract figures with airy brushstrokes, while Shayke wrote about current affairs with rumbling pathos. Leon delivered Davar newspapers, while Shayke, who’d arranged the job for him, won the Sokolov Journalism Award for his influential column in that same publication. Leon, who later found another job at the Israel Electric Corporation, would bring snakes and crabs home from the Yarkon River, where the power plant was located, while Shayke popped back home for a quick lunch of reibak and elzaleh— obscure stews from his Ukrainian hometown of Kovel, once prepared by his mother and now recreated by his sister Luba, my paternal grandmother, who kept her maiden name—Shayke’s name—and whom he supported financially.

Leon died when I was seven years old; Shayke when I was four. I only knew them through my father’s stories, a sophisticated sieve of irony. When I was little, it was tightly woven with grievance, but over the years, as my visits on Lipsky Street diminished, my father appeared pacified, or perhaps just eager to be heard. “I don’t know if Elik ‘came from the sea’,” he once murmured as he rummaged through my university reading materials, “but with what we paid, he could definitely spend some nice afternoons at the beach.” Elik, whose provocative sea statement had “epitomized the Zionist negation of its Jewish legacy,” according to my professor, was the author surrogate of Moshe Shamir, a celebrated author commissioned to edit Shayke’s collection of essays (the cover of which my father designed, for free).

One day, Dad pulled me out of the room for a “crawlspace clearing mission.” Up there, we found a bronze-like bust of Shayke which turned out to be made of crumbling plaster. “Oh, well,” he said with a devilish grin. “Sometimes words are unnecessary.” But when I asked why Shayke and his wife Pola never had any children, his face darkened and he refused to discuss the matter. About Leon he spoke sparingly and with kindness, even when he reminisced about how his father was away from home a lot, or how, as a child, he had to develop asthma just to get his attention. His stories painted the image of a detached, flakey loner, an absent father who was more naïve than tough.

Over the years, we spoke of the two men mostly as allegories for myself, in endless, indecisive discussions about “the divide” between writing and participating in the world, being a partner and being a hermit. “What, you think I don’t know all about it? That’s the way it was for me at Arieli,” he would begin, referring to the advertising firm where he used to work. When he graduated from art college, my father started an independent design studio that left him enough time to paint. He even showed his work at an exhibition and received some media attention. But in 1985, when I was one and my older sister four, the Bank Stock Crisis hit and he realized he’d better take what he could get. He accepted a full-time job as an art director at the advertising firm, a job he kept for 17 years, until he moved here. “But that’s bullshit, too. I remember myself standing in front of the blank canvas and simply having nothing to say. Hanging out at the beach wasn’t so bad; getting ‘inspired’. The canvas stayed in the studio. No, forget excuses, those who really want to do something just do it.” At that point I had to remind him, often in a rebuke, that we were talking about me, not him. I was not a fan of this giddy fatalism—what happened once shall happen again, and that doesn’t really matter either, it’s really all about the pleasure of conversation. But the conversation always took place at the expense of study or writing time, and I would sneak defiant peeks at my watch.

“I’m just using myself as an example,” he said. “Here’s another one: my father. He always said, ‘The only thing I give my job is time.’ He worked at the electric company until noon, and that was it. Then he painted. No night shifts at a news website, no trips to Vietnam. Pain-ting. If the passion burned in you, you’d be like him and that’s it, and the world would accept it.” After a brief silence, perhaps in light of my infuriated expression, he added, “On the other hand, things are different now. You don’t have that kind of privilege. Why don’t you find a job that can be your creation? Look at Shayke. For him it all went together. Essays no one could understand and senior governmental positions. Maybe it’s possible. Take Amos Oz. He had one pen for prose and another for journalism.” I explained that the situation wasn’t the same: Amos Oz, like Shayke before him, worked within a diverse literary system. I reminded him how briefly my collection of short stories survived at the discounted titles table in large bookstore chains; I quoted mythical editor Menachem Perry, who had, in those days, declared the death of the literary republic.

“So that’s the difference between you and Amos Oz, the ecosystem?”

“That’s not what I said.”

“Didn’t Amos Oz happen to fall asleep ‘of exhaustion and sorrow’ while writing on the back of an art book in the bathroom?” And before I could even answer, he added, “Well, at least you finally have something to blame your parents for: we didn’t bring you into the world at the right time!”

That was a reference made to another popular genre, in which he attempted to extricate signs of frustration, anger, rage, or distress out of me, especially since the divorce. My parents were raised by second-generation Holocaust survivors and birthed me straight into the society of plenty of the early 1990s. They were both proponents of psychoanalysis who believed in its tenets unquestioningly. I was 15 when they decided to get a divorce, and they found my equanimity unreliable. They saw me as a tightly wound coil, and went out of their way over the years to try to loosen me up. At that point in the conversation, when I realized I could not control not only its length but its content, I’d shut it down without warning, returning to the study.

◆

Two of Leon’s paintings hang on the wall, on either side of the window. One is a gouache on paper, my father explains, from the final years of his life, when he was too weak to stand in front of the canvas. They are affixed to the wall by new nails that hang out of the wall more than they burrow in, as if they hadn’t been hit by the hammer more than once. I have trouble relating to the shapes and colors of lyrical abstraction. Even after long moments of observation, they don’t inspire any true impression or sensation in me, and I therefore decide to start with the older nails.

Like me, Shayke was incorrigibly textual. His writings are gathered in four volumes, a bibliography, and another thin collection of letters and notes written to his wife, Pola (I knew Pola well. The last story in my first book is based on her). When Moshe Shamir eulogized him, he said, “The gestation and birth of these volumes occurred in the newspapers, while their honor, their greatness, and their eternity lies in Hebrew literature.” From the single, improvised bookshelf set in this room today—a wooden plank supported by two IKEA trestles—I pull the tome of Pirkey Yotam from a sealed plastic bag. The books contain references to subjects that are still at the top of the agenda, conveyed in solemn hyperboles that would be unimaginable today: church and state (“There is no joy in seeing religion—a handsome pinnacle of human faith—offered for sale by peddlers of quotidian politics”); the desired character of Jerusalem (“Perhaps it is not outside of the true concepts of culture not to have the city overtaken by stalls of Eros or Dionysus or other Hellenistic figures”); criticism of concern for the rights of Palestinians on the one hand (“More than it is guided by the love of the Stranger, it is guided by a hatred of oneself”) and of the incarceration conditions of terrorists on the other hand (“The question is not how can we live with our neighbors, but how can we live with ourselves and our instinctive sensitivity toward a human tear”). An earlier column, from 1963, remains strikingly relevant: “Israeli democracy does not need this kind of whirlwind right now… Our division across Party lines and political temperament transform any Israeli election campaign into an all-out war, tossing every possible topic into the bonfire of polemics… leaving behind scars that our public lives often cannot recover from in the long term.”

The introduction by Dov Sadan, who was a prominent Israeli literary figure, offers some confirmation of the hints my father had scattered over the years regarding the various strings Shayke had pulled and the many hats he’d worn: “He is a man of letters, and many worldly affairs—in public matters, as a civil servant—a fact which is not obvious in his writing, but without which his biography would not be complete.” A review by Ari Avner in Iton 77 teaches me that Shayke was blessed with a “talent for moral uprising,” which is none other than “the ability to see things in their initial glow as if through the eyes of a child discovering the newness of the world and the purity of ideals, before nurturing defilements and depressions.” Which, on the other hand, did not prevent him from “rejecting fads that pop up in the morning and grow outdated by that night, both intellectual fads and what our ancestors used to refer to as ‘schmendrick-isms.’”

In the collection of his letters to Pola I find carefully measured stanzas on Trade Union stationery, expressing a passionate love and unapologetically employing pet names that are nowadays used only by the parents of toddlers or corner store owners. But the true surprise awaited me in the bibliography put together by Yossi Galron: As it turns out, Shayke was not only an accomplished Trade Union figure and a prophetic polemicist on par with Nathan Alterman, but also a translator, like me. I flip through, astounded to find a translation of The Fox and the Dates, an adaptation of the Aesop fable by Brazilian playwright Guilherme Figueiredo; a book about novelist Shalom Ash, and another translation—115 typewritten pages—that had been completed but never published of The Emperor and the Rabbi, a play by Zalman Shneur, whose namesake street is right down the block from where I live.

The more I read, the more convinced I feel that I hadn’t only missed out on Shayke himself, but on the world from which he came: a world where the pen was mightier than the sword, a world that would not have turned up its nose at a flowery or embellished turn of phrase, but rather appreciated its worth—a world in which I may have fit in. “ Sometimes it seems as if Avrech is not after the convincing expression itself, but after the might of the expression,” Ari Avner wrote, echoing with veneration the same statements that have been directed at me from the day I started writing, mostly intended as criticism. Shayke died in 1988; the collection of his writing and the reviews I’m quoting were published in 1990, only two years before the publication of Etgar Keret’s breakout short story collection Pipes and Orly Castel-Bloom’s ground-breaking novel Dolly City. Reading Shayke’s work evokes a sensation of the changing of the guard.

Leon, on the other hand, had no part in such upheavals. The National Library of Israel’s journalism archive includes 39 mentions of the name, which he shares with a criminal lawyer who was involved in sensational murder and rape trials (Shayke comes up 268 times). Leon won the Dizengoff Prize in 1937 and 1944, represented Israel at the Venice Biennale three times, but in the course of a career that spanned more than 50 years, he only showed his work in a handful of solo exhibitions around the country.

“Leon Fine might be perceived as a painter returning from oblivion,” a Ma’ariv interviewer declares on the occasion of Leon’s final solo exhibition in 1977, when he was 71 years old. “He is not one of those oft-discussed artists, the trendy ones who lounge around the cafes, and whose fame is propelled by a lack of humility. Nor is he one of those who demure in order to win a modesty contest. Leon Fine is a truly, genuinely humble, unpretentious artist.” In another interview for Davar on January 31st of the same year, Leon himself confirms: “I’ve always been an anti-hero.”

This all sits well with the figure I knew, but a more careful reading reveals a new facet of him that I could not have encountered through my father’s irony. “‘I’m an optimist, I’ve always been,’ says Arie Leon Fine, full of kind-hearted smiles.” That is how the Davar interview starts off. “I paint imaginary landscapes. I conjure spots of scampering foliage colors. There, that triptych—I painted it just after my son got married. I was so full of joy. That was my expression.” (“Sure, ‘my son,’” my father, the son, comments, “he couldn’t remember if it was me or my brother.”) A 1942 review of his solo exhibition at Beit Habima Gallery by Haim Gamzo describes a bold artist who uses smooth color rather than layering, and, in opposition to the “en-vogue provincial pseudo-puritanism,” does not hesitate to show nudes. And though Gamzo criticizes the large number of pieces shown in the exhibition—“Fine showed 60 paintings, which is a shame! Each one is a link in the chain… but the chain’s major drawback is that it’s too long”—he ultimately determines that Leon “does not stagnate” but is instead “immersed in an endless search for his selfhood and his own private language.”

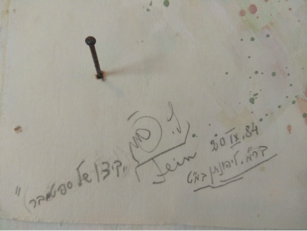

I look at the wall again, hoping to adopt some of that “sense of the primary derived from a near childlike view of the world,” but the discovery awaiting me is neither metaphorical nor interpretative. In the bottom left corner of the picture hanging above my head, I spot a line of writing I hadn’t previously noticed.

My father does not remember the painting, but he explains that the numbers represent a date, and not—as I thought—the size of the canvas: not 20 by 84 then, but September 20th, 1984—two weeks after I was born. The acronym “M.T.” turns out to stand for “Mazal tov,” but the second one—“B.M.R”— presents a mystery. The B and R must stand for Best Regards, but the M is an enigma. My father exhibits growing interest in it. He distractedly barges through the closed door to stand before the painting, over my head, for lengthening periods of time. I don’t protest. Knowing that the painting was a gift for the occasion of my birth motivates me, and when Dad finally leaves the room I forget the wall for a while, returning to what had brought me here in the first place: the ultimate individualistic step.