I was the last one to arrive, as usual. The six other women were in their folding chairs arranged around the bright green rug with its jaunty ABC’s. The only empty seat was directly above the M, next to Ash, who was already looking angry and finishing a burrito, which was against the rules (no outside food or beverage). They hadn’t started check-ins yet. They were still chatting casually in groups of two or three and fussing with the babies.

As I slipped through the door, Sola and Charmaine both looked up at me in confusion. My heart fluttered with the realization that these women had likely forgotten my son already. Forgotten Jack and therefore forgotten me because Jack was the only reason I’d ever been to mom’s group. If this was true, they wouldn’t be willing to help.

But then Ash raised her eyebrows at me as her mouth closed around her final bite and Sola said, “Where’s Jack?” and relief flooded over and through me.

These women still remembered him. For all I knew, they were the last people in this world who did.

I slumped into my seat and said, “Actually, that’s what I want to talk about today. If I can check in first?”

I didn’t wait for them to answer, just started speaking.

“Jack’s in trouble,” I said. “It’s hard to explain, but trust me when I say the trouble is bad, it’s scary, he’s in danger.” I looked around. Six stunned faces, one of them licking burrito grease from her fingers. But at least they didn’t look dubious, not yet. “And the thing is no one’s in a position to help. Not even Adam. It’s all on me and—”

I stopped, considering how to phrase this next part. No one interjected with a question, not even Ash. This allowed me space to think, which was helpful because I’d been having a day that was hard to report on without losing credibility. My son had disappeared from his crib and, since then, one by one, people had been forgetting that he’d ever existed. I was no great expert on intimate confidences, but even I knew you don’t just go into your new mom support group and start talking about alternate realities, or how bad odds are erasing all traces of your child. So what, then? It’s all on me and, it’s all on me and . . .

“I need my mother,” I finally said. “I need my mother’s help. She’s the only one who can help, but we’re not—we’re not in touch. It’s hard to explain. But I need—I need to do something, kind of go deeply into myself, if that makes sense, deeply into myself in a way that will help me reach out to my mother. I need to go so deeply in I’m afraid I might not come back out. So I need you guys to, to, I guess just to be there with me? Be my anchors, help pull me back to the here and now when that’s where I need to be. Would you be willing? I know it sounds nuts.”

Through this all, as per the guidelines we’d agreed to, all six of them just listened. “A place for non-defensive, non-judgmental listening” had always sounded to me like marketing bullshit, an impossible promise, like endless shrimp, but goddamn if these women didn’t do exactly that, even Ash beneath her fiery bowl cut. Their faces as I spoke had contorted through sadness, horror, fear, then frank confusion, and by now it was clear that every last one of them had decided I was not an entirely sane individual. But they had listened.

They had listened and now no one was speaking. It was possible that no one ever would, and I couldn’t say I blamed them.

But then Ash said, “So am I understanding correctly what the ask is? You want us to just sort of be here with you, while you do this thing you need to do to reach your mother? That’s what you’re asking?”

“Yes. That’s right,” I said, trying to at least sound very pleasant, if not exactly a model of mental health. “And maybe, like, hold my hand? Maybe two of you, one on each side?”

It steadied me to hear my voice describe this task in terms that made it sound concrete, a matter of getting the numbers balanced, like a square dance. The truth was, what I was trying to do was less like dancing a metaphysical quadrille and more like hurtling one of the dancers (me) straight out of spacetime and seeing if maybe I could stick the landing. All so I could find my mother. I hadn’t seen her in thirty-one years, could remember her only piecemeal, but she was the only person who might know how to do what I was trying to do now for my son: save him from the infinitude of possibilities he was riding like a slow motion tidal wave, and bring him home. She’d done it for me once.

But as for reaching her, well. . .my mother was no longer such a simple thing as a person, someone you could call or text. She was a whole origami spacetime matrix of a woman. She was looking out of every pair of eyes of every version of herself in every branching reality. I had to find a version of her, any version of her, and try to snag her strange attention. If I could find her, if I could summon her, then I was pretty certain she could tell me how to save my son.

Ash said lightly, “Sure. I’m game.”

Sarah, the very young facilitator, cleared her throat.

“This is not really what the group is about though?” she said. “We’re a space for processing, is the thing. Not for doing. As absolutely harrowing as this must be for you, Hannah, and my heart truly breaks for you, it truly does, and I know we’re all now feeling scared for Jack and hoping that whatever it is he’ll soon be A-OK, but I’m not sure this group is the right place for—that. We said ‘no’ to Charmaine doing her pitch for the cloth diaper service, remember.”

Ash said, “I’m sorry, is this not a group for mothers supporting mothers?”

“It is, but through talking.”

“Sarah, no offense,” Ash said, her voice already thrumming with her characteristic rage, “but you’re the only one among us who’s not a mother, so I think, and pardon my being blunt here, but is this not just painfully obvious? I think you have less say about what counts to us as support.”

“I wrote that mission statement,” Sarah said weakly, but it sounded like an admission of defeat.

It seemed like this might actually be going well.

And then Charmaine said, “I’d like to do it. I’d like to help.”

“Me, too,” said Kate. “I’m happy to do whatever Hannah needs.”

Sola and Devaki were in agreement. Sarah looked like she wanted out, but she wasn’t going to stop us. She wasn’t even licensed yet, poor woman.

“Are you serious?” I could not entirely believe this. “You’ll do it?”

Ash said, “Why not? I mean, it doesn’t sound very hard. We just, like, hold your hand while you kind of, like, do a weird, intense meditation, right?”

“Right,” I said, and God bless Berkeley, this might not have even been the strangest thing they’d been invited to participate in this week. I mean, Sola had invited us all to a druidic blessing of the babies at summer solstice. I’d never RSVP’d, which now I was regretting.

They didn’t care if what I was asking of them was reasonable. They didn’t care if they believed me. I loved them madly, these women I’d never fully known whether I liked.

We all scootched our chairs in closer. Some of the babies in the center of the rug took issue with the commotion and needed to be soothed, but that was accomplished expertly and quickly.

Ash took my left hand. Sola took my right. I looked at all six of them in turn, memorizing their faces in case I needed to use these details to pull me back. Sola’s small pink mouth like a candy heart and the mole just above Kate’s left eyebrow, and Devaki’s seriously good bone structure. The small curls escaping Charmaine’s bun. The intricate lattice of pale freckles across Ash’s cheeks and nose. Sarah’s chin sunk down into the cowl-neck of her sweater.

Then I said, “OK.”

I closed my eyes. I tried to feel along my thoughts for my mother’s arms and voice and smell, impressionistic and hard to grasp, but hinting at a whole lost continent of memories. One: A face coming down from above, closer, closer, laughing. Two: A warm-bellied contentment. Gorgeous slivers of recollection, and yet the feel of them was a howling, a too-much-ness, black and threatening. I braced against them, and squeezed the two hands offered me as I tried to open myself to these feelings that I had learned were doors. It was like trying to coax my body to jump from a high building. I was too afraid of these dark and hungry feelings, of what they’d do to me.

I opened my eyes. Looked at the babies in the center. Thought of Jack, his loamy bread smell, his delighted squeal. I closed my eyes and tried again.

Ash was saying something, maybe about the blood leaking from my nose, but I was finding it hard to hear. My ears were rushing with a sound like the whoosh-whoosh of a fetal heartbeat on an ultrasound. I was pretty sure this was my own heart pounding.

I was bent over my lap. My whole body was trembling, and Ash and Sola were still managing to hold tight to my hands. They were doing exactly what I’d asked of them, and it was working, something was happening, but it wasn’t enough because I couldn’t open myself to these feelings, I was too afraid of letting go of this world and never coming back.

I opened my eyes. Stared at the babies. My mother was going to take this, too. By making me too full of fear, she was going to take Jack from me by taking away my ability to save him. Just like she’d taken herself and ruined any chance I’d ever had before a single chance unfolded.

I started to scream.

Then I was somewhere else.

◆

I was staring at the shimmering yellow dollop that bounced and shivered and shot off light in the very center of Dr. Goodman’s generous bay window. Like an eggy glob of sunlight. Like naked strands of DNA.

I wasn’t sitting in the womb chair but on Dr. Goodman’s couch. I never sat on the couch. It was reserved for couples.

I looked to my left, and there was Adam. Sitting as far from me as he could possibly manage while still occupying the same piece of furniture.

He looked thin. And underslept. He was holding himself like he might bolt at any moment. Like he was here under duress.

And in fact he was saying, “I don’t see what she hopes to gain from couples therapy when we’re no longer a couple. I don’t mean that to sound cruel. I just—I’m trying to move on as well, and this feels counterproductive to my own progress. I’d just like a clearer understanding of what we’re doing here right now. Together.”

“Speak to her,” said Dr. Goodman. “Not to me.”

I turned my gaze to Dr. Goodman. Her auburn hair was falling in a perfect wave over one eye. Her black satin pencil pants were creased to a knife-edge point, and I wanted to lay my cheek against her crisp white shirt.

I wanted to tell Adam to give us a second here, maybe step outside, so I could explain to Dr. Goodman what was going on. I wanted her to listen, nod in her unflappable way, and tell me that she understood. That she was sorry to have lost faith in my sanity in some other possible world; that she was sorry to have lost faith in me. To have abandoned me.

But this was a distraction.

The wrong abandonment, the wrong loss. Two wrong losses, actually. Adam. Dr. Goodman. And it made sense, I guessed. It wasn’t such a simple thing to ride the possibilities, to cleanly separate out feelings for one person or another.

Still, I tried to focus in again on that more specific longing, a longing that was a rage against everything I’d lost—was still losing—when my mother went away. Her absence had formed a void that had howled through me so loudly and so long that I had come to think of it as simply the sound of me. Instead of closing my eyes, this time I stared at the eggy dollop in the window.

The dollop was wavering in and out of focus.

I looked back at Dr. Goodman. But Dr. Goodman was drawn in streaks now. Black shadows passing over her. Black shadows becoming her.

I felt an awful searing behind my eyes. And then a wrenching. As though my whole body had been flung against a wall without my moving from the couch.

The view swung wide.

I was clacking down a marble hallway. My toes felt pinched. My heels were starting to blister. I was wearing stilettoes. Jimmy Choos. I couldn’t imagine a reality in which I’d spend so much money on shoes. But apparently I was in one.

I was in a slick corporate building refashioned from a church. Soaring windows many stories high let in a gray afternoon light. To my left was a low glass partition that I knew, without checking, looked down on an atrium far below. These were the offices of my London publisher. And the woman clacking beside me was my British editor, Maureen.

Maureen was saying, “We’re all mad about it naturally. It’s so different. So surprisingly different. I had no idea you could write scary.”

My head was turned so that I could look at Maureen’s pale oval of a face, her lips in their habitual nervous twist. Maureen wasn’t being dryly witty. She was being sincere. This was a reality in which I wrote books that weren’t scary.

The Jimmy Choos I could almost just believe. But that I wrote books that weren’t repositories of unease was too hard to wrap my mind around. This seemed promising. This was clearly a world quite different from my own.

“I’m so relieved you like it,” my mouth said, although the words were not mine. I wasn’t even sure that I could move this body, make it speak. It didn’t feel as though I could.

I was surprised to hear the voice that came out of my mouth. It was only a little bit like the voice I knew as mine. It was slower, for one thing. Took its time and made the listener wait. But also deeper. And louder. And somehow richer, too. It was a very good voice. Impressive. It took up more space than mine along every dimension.

“I like it very much. But it’s as the group from marketing were saying, it’s more a matter of positioning. We just want to get it right. When you have a built-in audience the way you do, what you don’t want to do is put them off.”

My head nodded, but, again, this was not my doing. I was feeling along the thoughts skimming beneath my own, searching for a way in, trying to understand what had brought me here, and how it could lead me to my mother. But the mind of this Hannah felt closed. This was a distant world. A distant version of me. I couldn’t get a purchase on this Hannah.

We’d reached a bank of elevators. My body leaned against the marble wall, giving the battered feet some small relief.

Maureen was saying, “I should be cross you aren’t letting me take you to lunch. I still want to talk about the other book, the motherhood as hero quest that I was promised. But Thursday?”

“Thursday,” my mouth said, and I was again unnerved by the voice that greeted me, like mine but so much better.

The elevator pinged open. Maureen delivered me inside with a limp hug.

I closed my eyes. Something from this rich-voiced Hannah’s mind was finally getting through now and distracting me. It was the person I was heading downstairs to meet. I was wonderfully eager to see them. I was jittery with the pleasure. It was possible, it was very possible, that this person was my mother.

I didn’t want to leave, not now, not at all, but for some reason the searing was starting up again. I wanted to press my palms into my eyes, to stop the process, but I couldn’t lift these hands.

The doors pinged open. A group of men got on, conversing softly. I felt a lurch, as if the elevator had shot sideways. I reached to grab hold of the wall, but instead of metal my fingers touched the wool of the couch in Dr. Goodman’s office. I was back in the world where Adam and I were sharing in an ill-advised counseling session.

In Dr. Goodman’s generous bay window, the eggy dollop was shooting off its gorgeous light, the late afternoon sun streaming around it.

Adam was talking.

“—that story about when my sister had a crash driving from Montreal? Her car was totaled. She wasn’t hurt, but she was a wreck. And when she called my mom, the only thing she said she wanted was for me to be the one to come and get her. Two hours there. Two hours back. I didn’t want to. I was eighteen and home from college and feeling lazy, but that’s not really why. I don’t know how to explain it. I just—the fact that she wanted me to so much made me not want to do it. That was all. And so I didn’t.”

Dr. Goodman’s face was a studied neutral as she looked to me for reply.

“I know that story already,” I said, because I did, although I’d never liked it.

“Does it strike you any differently, hearing Adam offer it as an answer?”

Dr. Goodman was giving me a very strange expression.

I felt beneath my nose again, but there was nothing. No nosebleed, but also no cause for a nosebleed. The door to my own world, which I’d been trying to keep propped open, had shut. I was only in this world now.

“The answer to what?” I asked, distracted by the discovery that I’d lost my hold on my own world.

“To your question, Jesus, I’m not the one who asked you to be here in the middle of the day.” Adam’s voice was pleasant. I generally hated when Adam said angry things in a pleasant voice, but right now I didn’t care.

I’d lost the stream of information from my own world. Just like I’d feared would happen if I went through the doors that connected me to my mother. I couldn’t see or hear the six women arranged around the round green rug in folding chairs. But somehow I could still feel the two hands holding mine. Anchoring me like I’d planned. Whether this would be enough to get me back I didn’t know, but there was no point in worrying about that now. I just had to keep going.

“Hannah?”

Dr. Goodman’s voice was trending toward alarm, although her face didn’t match the sound.

This time I didn’t try to focus so fixedly on the longing. I didn’t try to force it. I tried instead to do what I had never managed to do with Dr. Goodman, when she said, “Don’t think, just speak. What comes to mind from there?”

This time, at least, the wrenching was less violent. It was smoother, slower, and it gave me time to analyze the sensation. Like a full-body Charlie horse crossed with a flicker of insight.

And then I was clacking in my red and tan Jimmy Choos toward a set of large glass doors. The eager anticipation I’d felt in the elevator was even stronger now. I couldn’t wait to see the person waiting for me on the other side.

What I was feeling, what this Hannah was feeling, was opening to me.

Like a foreign language I was finally feeling my way into, the language of this Hannah’s feelings was speaking loudly now, excitedly. And what it was saying, as far as I could tell, was wonderful. Almost like a golden light glowing within me, flowing warm and comforting beneath my skin. It glowed stronger the closer I came to the doors, to whoever was waiting for me on the other side.

I pushed through the doors, feeling giddy, but there was no one. Just a busy London street.

I focused without focusing, the searing starting behind my eyes, and with only the gentlest of tugs the busy London street became a beach. I was standing knee-deep in greenish yellow water that sparkled into turquoise just a couple of feet away.

The sand back on the shore looked pale and soft. The beach was empty except for me and Jack.

Except it wasn’t Jack. It couldn’t be. The child who felt to me like Jack in every way was dog paddling back and forth in front of me. Was six or seven years old. Was female.

“Mommy, are you watching?” this child shrieked delightedly, water trickling from her mouth as she struggled to hold her head above the gently lapping waves.

This world. This world was wonderful. The golden light was still glowing warm inside of me, maybe slightly brighter. Maybe because of the girl. With her nut-brown skin, her high-arched eyebrows that I loved to trace with a finger, but these days only when my daughter was asleep, because otherwise she wouldn’t allow it.

The light playing over the turquoise water had a certain familiar quality, a softness that seemed to clean whatever it touched down on. The curve of the shore was familiar, too. It reminded me of a beach toward the very tip of Cape Cod, where my father and I had rented the same house three summers in a row, a house he’d also rented with my mother for a week when she was pregnant. It was a wind-battered old place that felt like an ancient ship and I’d loved it. Just for being a place that my father had chosen to take me, a connection between our current life and the one that had included her.

I turned to look for the house. It wasn’t there. And neither were the dunes in which it nestled. So not Cape Cod, then. Or not that beach.

I dipped into the skim of thoughts beneath mine, searching for a location, for some sign of my mother near, but already the searing was beginning. Already, I was leaving. Not even a gentle tugging this time. It felt as smooth as stepping between rooms.

I was standing at a kitchen counter looking out the window at a winding road lined on both sides with tall, pale grasses. I was still near an ocean. I could smell it in the air. Sharp and briny with undernotes of decomposing seaweed. In the distance, seagulls circled. There were clumps of sand amidst the tall, pale grass and on the asphalt of the road.

On the counter in front of me was a blue and white ceramic bowl filled with Caprese pasta salad. I picked the bowl up. Turned. A woman was sitting at a yellow farmhouse-style table just behind me. Her back was to me.

The golden warmth inside of me flared so strong that standing here, just being, was almost too good to believe. Was this a way that people could feel? Might I have been interacting all my life with people who secretly felt exactly like this? The question sent a ripple of displeasure through the lovely golden light beneath my skin. I took a few steps toward the table, toward this woman.

She turned to smile.

“Oh, that looks lovely, sweetheart,” my mother said. “Just like your father used to make. Do you remember those summers on Cape Cod? All that sand you could never get out of the sheets and the towels always damp and Neil always somehow surprised by it, each and every time? ‘Eva, this towel is wet.’ No fucking kidding, Neil.”

My mother had long gray hair held back by a tortoise-shell barrette. Her eyes were narrow, twinkly, alive with good-natured mischief. Her face was beyond describing. So beautiful that I almost couldn’t stand it, although it was impossible to say what made the wrinkled, thin-lipped face so lovely. Just looking at it made me feel weak-kneed with joy.

I almost dropped the bowl, then caught it.

I was weak-kneed with something else now. This was what it felt like to have a mother. And for a moment, just a moment, I’d forgotten my own son.

I tried to open this mouth. I tried to speak. But this Hannah was too distant a version of me. I had no sway over this body.

And my mother? It was hard to believe that anywhere inside this twinkly-eyed woman was the mute, rocking mother who was mine. That my mother, spread between the possibilities, really crouched in any corner of this healthy mind. But if I was right, my mother looked out from all her eyes in all her versions. And I had to believe that I was right; I had nothing else.

Which meant I had to find a way to get this body to speak. This body put the bowl of pasta salad on the table and took a seat.

My mother’s fingers were smoothing back a few strands of gray hair that had escaped the barrette at the nape of her slender neck and were flying loose around her regal forehead. The hands moved smoothly, elegantly, the motions young and fluid. But every few seconds the head jerked to the right in a painful-looking spasm. Perhaps she noticed my noticing.

“I’ve got a funny crick,” my mother said, moving her hands to rub behind the neck.

I could have laughed if my laughter worked inside this body. Just as one of the other Hannahs had described it: a post-hoc justification. Maybe it was a tic, just like she said. But maybe it wasn’t. Maybe instead it was my broken mother inside this healthy mind, forming her own intentions.

I couldn’t shift my gaze to see what it might be that my broken mother maybe wanted to look at. I couldn’t even work this body that small amount.

But it didn’t matter. I’d found it now. The way to wield some sway over this body.

I was feeling the photo negative of that golden glow. How much I’d lost. How much I wanted.

It was a howling all through me, and it tied me somehow to this body, just enough. Bit by bit, I pulled the jaw down, an unhinging, a prying.

And then, in this charming room, at this well laid table, at a cozy family gathering over bowls of pasta salad, I made this Hannah scream.

Almost a word, almost “help”, but as it might sound in a mouth incapable of forming human words.

It was a scream that could have come out of my mute and rocking mother. But it hadn’t. It had come out of this happy, golden Hannah. Right into her mother’s startled face.

I’d done that. I’d done it. I had made contact.

I felt for the two hands holding mine, I lurched. I was on the green rug, which was speckled with my blood. The women and the babies had all huddled on the far side. Even Sola was only barely maintaining contact between our fingertips, the rest of her leaning away.

Only Ash was still right here. Her hand still holding tight to me. She kneeled down now, brought her face just inches from mine.

“Holy shit,” she said. “Was that a seizure, or was that the thing you wanted to do? Did it actually work?”

I struggled to sit up with Ash’s help, my whole body still trembling. Sarah had run off to get me a wet towel, and now she returned with it. Charmaine took it from her and began to swab beneath my nose. It was hard not to cry as she tended to me, her touch gentle but not pitying. The white washcloth was saturated with red. I had bled an astounding quantity, it seemed to me, but I wasn’t feeling woozy.

“Hannah?” Ash asked. “Did you actually just do something completely fucking awesome and insane?”

“Yes,” I said. “I just did something completely fucking awesome and insane. But I have no idea whether it worked.”

◆

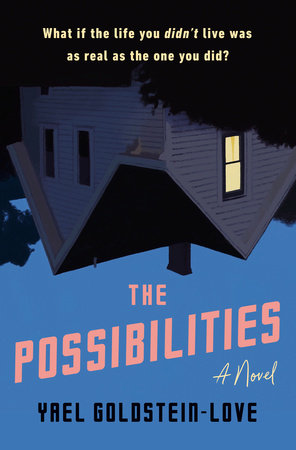

Excerpted from The Possibilities (Penguin Random House, 2023)